engraving

#

baroque

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 362 mm, width 288 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

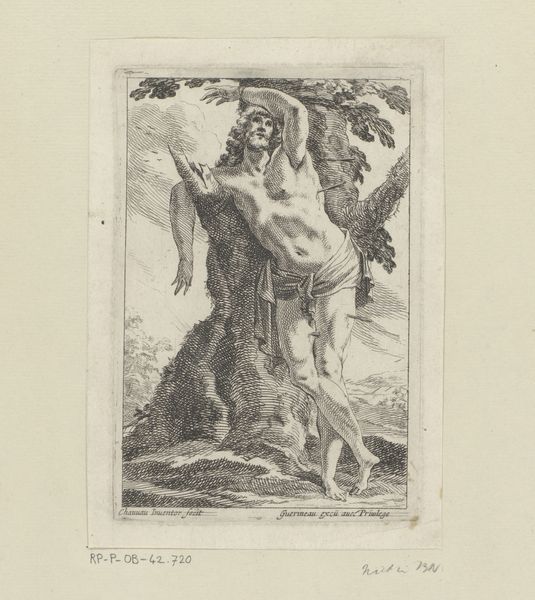

Curator: This engraving, created by Louis de Châtillon between 1672 and 1686, is titled "Fountain of Hercules and Antaeus" and currently resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Wow, there's something about the light and the movement that's absolutely mesmerizing. The drama pouring off that fountain scene is palpable, wouldn’t you say? It feels both fluid and rigid simultaneously! Curator: Indeed. It depicts the mythological struggle between Hercules and Antaeus. This print is significant because it documents and, in some ways, immortalizes, a public monument—in effect making it portable. Do you think that changes the narrative? Editor: Absolutely, it's fascinating! Instead of being a landmark fixed in space, this print turns it into a circulating image. So instead of feeling dwarfed by the monument's scale, as you might encountering it in situ, you instead have this much more immediate and intimate interaction with its symbolism. I mean, the way those muscular forms wrestle, it’s as if they’re exploding from the page right at you. And yet the way it's framed sort of tames that raw violence, right? Curator: Precisely. In its time, prints like this were vital for disseminating knowledge and artistic ideas throughout Europe. A Baroque monument celebrating power through classical imagery then gets turned into a democratic tool to reproduce and spread that vision of power more widely! This work acts as a historical artifact of artistic influence and socio-political ambition. Editor: I find myself dwelling on that fountain! What is normally associated with refreshment and even leisure becomes here almost violent in the way those cascades mirror the force of the figures above. It has turned liquid into both metaphor and mechanism. It's as if we are drowning with Antaeus, not watching him. Curator: It definitely gives you pause to consider how powerful classical allusions still were at this period in their propaganda, and to think about what stories we retell through public art now. Editor: A potent thought indeed! From static stone to flowing print—it really puts those old stories into a new light.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.