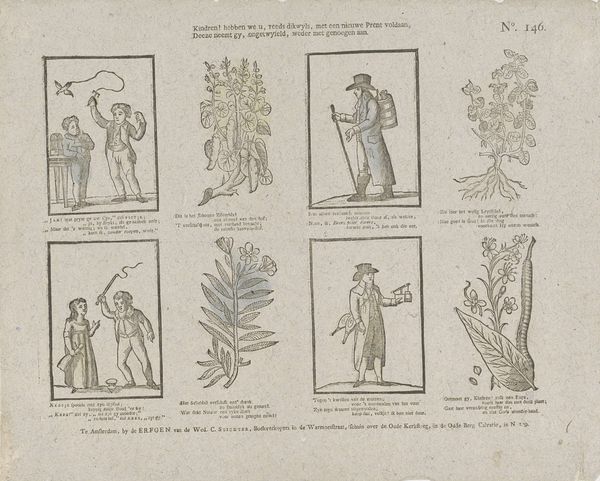

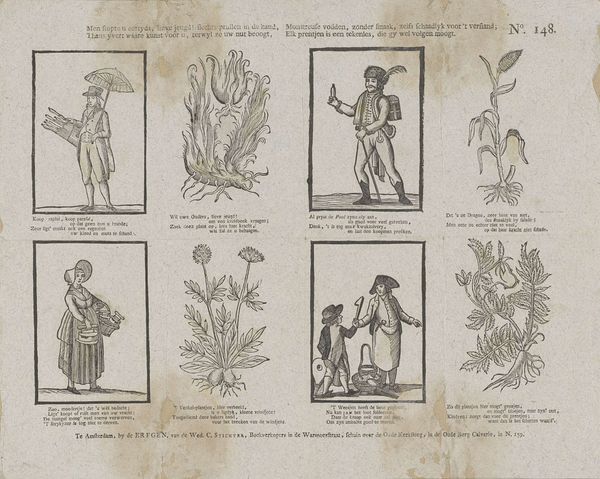

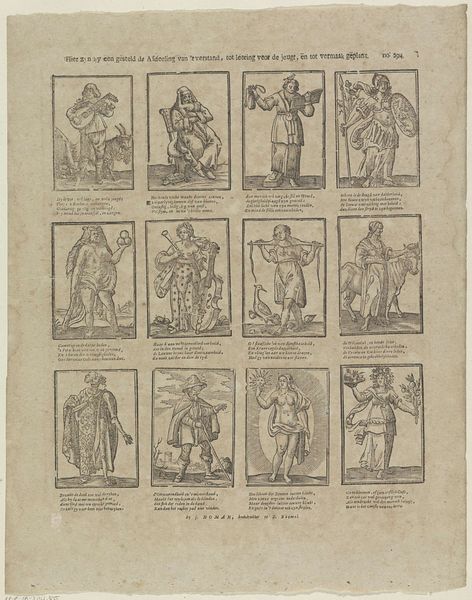

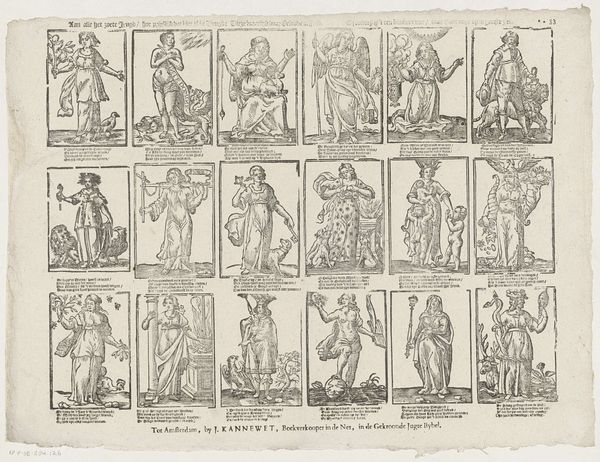

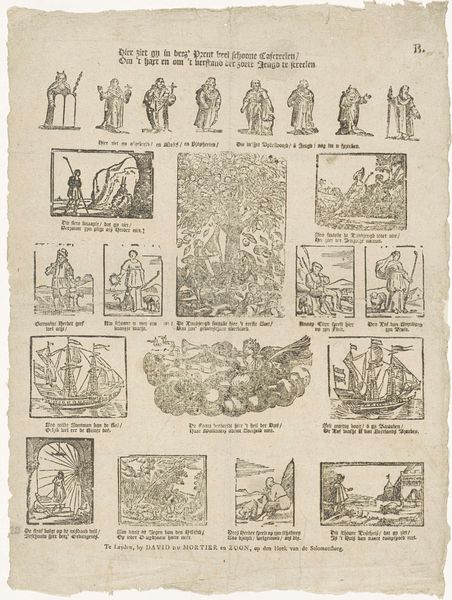

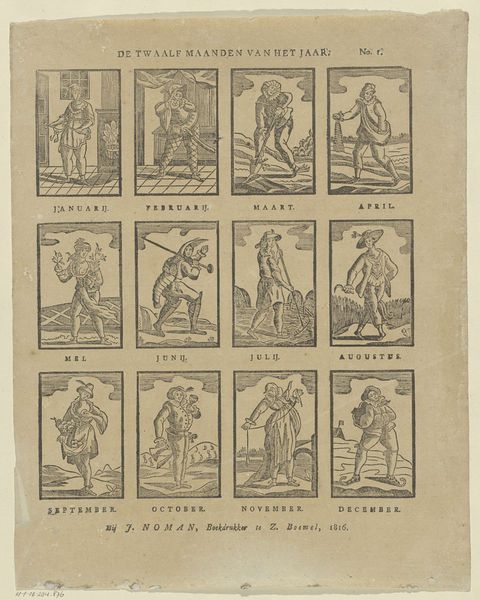

ô jeugd! beschouw hier, met verstand, / Uitheemsche liên, gewas en plant; / Dus moogt ge uw oog en geest vermaaken / Met deeze u voorgestelde zaaken 1715 - 1813

0:00

0:00

ervenweduwecornelisstichter

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 330 mm, width 412 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

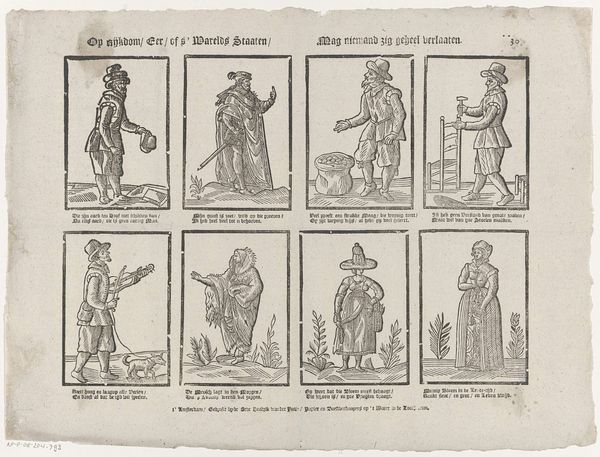

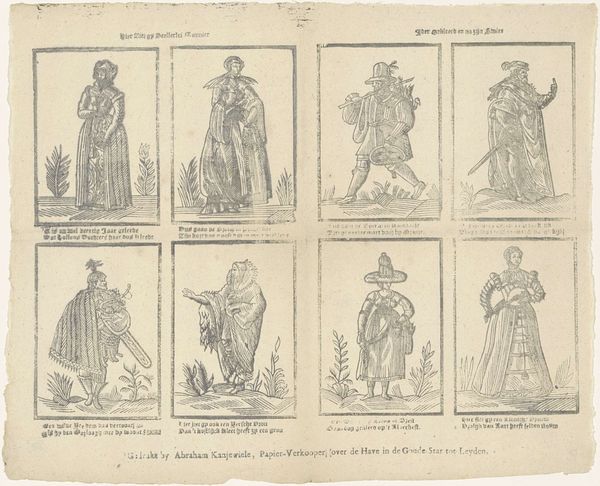

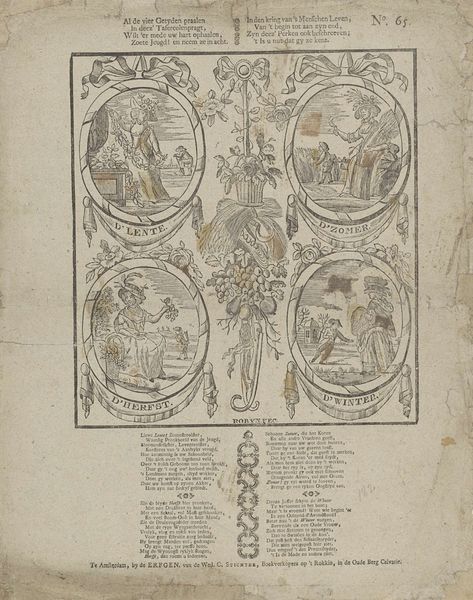

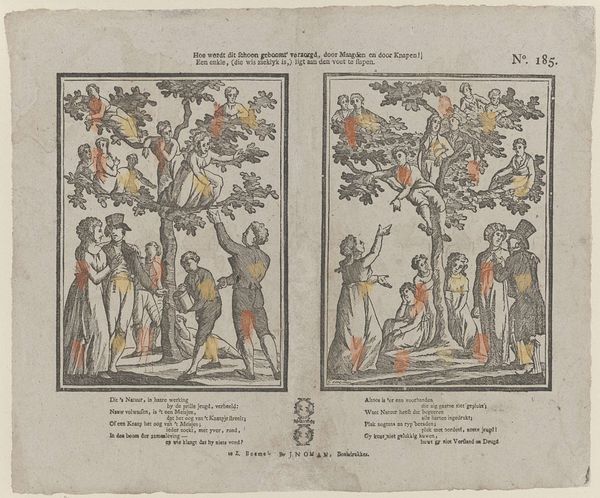

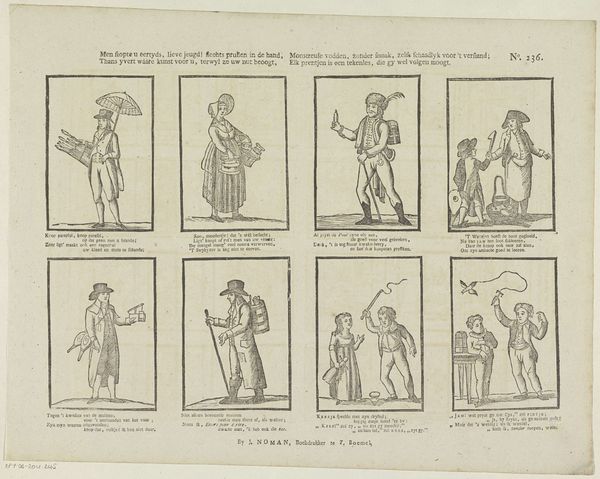

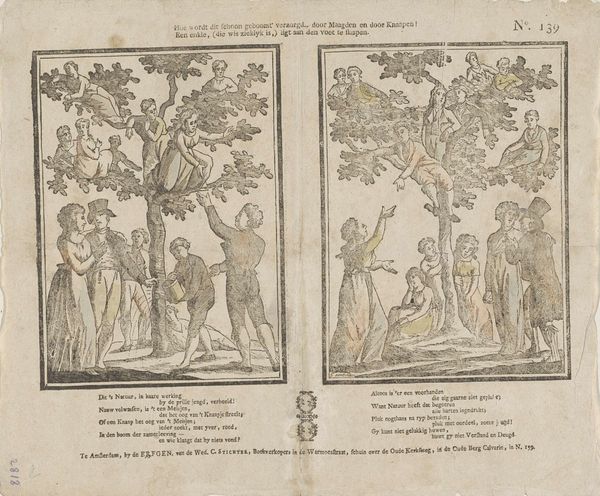

Curator: Look at this engraving from between 1715 and 1813, entitled “ô jeugd! beschouw hier, met verstand, / Uitheemsche liên, gewas en plant; / Dus moogt ge uw oog en geest vermaaken / Met deeze u voorgestelde zaaken." It's quite a mouthful! Editor: Wow, it's… densely packed! Like a botanical and ethnographic study all crammed onto one page. There's a strange orderliness that somehow feels chaotic. What’s your take? Curator: I see it as a window into early colonial encounters, depicted through a series of meticulously engraved vignettes. The juxtaposition of foreign figures alongside exotic flora tells a story of exploration and appropriation, all within the Dutch Republic's burgeoning trade networks. It shows a material culture clash. Editor: The figures look…flattened, almost like pressed flowers themselves. And the text! It feels like an attempt to classify and contain the unknown, reducing people and plants to specimens for study. There’s something unsettling about it. A colonial catalog? Curator: Exactly. These prints were often disseminated widely, contributing to a construction of the "other" and reinforcing notions of Dutch superiority. The very act of collecting, classifying, and displaying such images speaks volumes about the era's power dynamics and manufacturing the narrative about who mattered. Editor: But it’s the plants that pull me in. Rendered with such precise detail. Did the Dutch value them simply for economic benefit or because of genuine appreciation of these natural wonders, removed and labeled as something they weren't? Curator: It is not binary, Editor! Consider how botanical gardens functioned. Scientific inquiry intertwined with displays of wealth, power, and access to resources. There were even competitions, of sorts, around cultivated blooms, so the labor surrounding those items became associated with colonial one-upmanship. Editor: Thinking about it as labor helps to explain why those details are given a higher premium than the flattened bodies. Food for thought…well, and for the soul, I suppose. Curator: Indeed. By deconstructing the context of its creation and circulation, we get something like material evidence for how this society operated and its own forms of branding. It shows us its means of self-promotion through possession. Editor: It's more than just pretty pictures, then. This little print unpacks a whole history, a cultural tapestry woven with exploration, exploitation, and a thirst for the exotic.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.