oil-paint

#

portrait

#

gouache

#

fantasy art

#

oil-paint

#

romanticism

#

nude

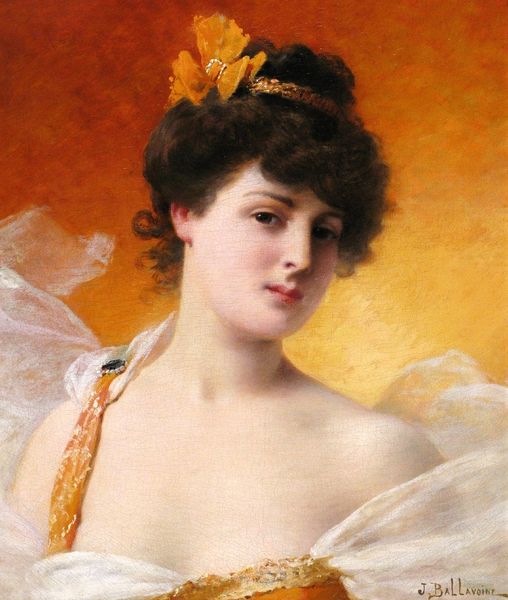

Copyright: Jules-Frédéric Ballavoine,Fair Use

Curator: Jules-Frédéric Ballavoine's "Young Beauty" presents a portrait in oils that resonates with a Romanticist aesthetic. Its date is unknown, but the artist lived during the late nineteenth century. What is your initial read of the artwork? Editor: It strikes me as serene, almost ethereal. The soft pastels and delicate brushwork lend it an air of wistful gentility, even vulnerability. The woman’s exposed breast complicates this immediate impression though, unsettling the conventional mood of similar portraiture from the period. Curator: Indeed, the use of oil paints enables such a luminous quality to the skin tones. Consider the materials used—the luxuriousness of the fur stole, the shimmering silk ribbon—these all point to a narrative of privilege and display and connect with commodity culture of the time. Do you consider those materials to influence a critical lens? Editor: Absolutely. The painting reads as a carefully constructed image of idealized femininity intended for display and consumption. The semi-nudity alongside her aristocratic air can be viewed as symbolic of objectification, revealing underlying power dynamics within representation itself and further linking high art to consumerism. Curator: Her gaze seems averted, reinforcing that objectification perhaps. It highlights the interplay between the maker, the subject, and the viewer in the construction of the art piece. We see the result of labor through the highly skilled work. Editor: Yes, the averted gaze contributes to that feeling, turning her into an object rather than a subject, mirroring a broader societal attitude where women's identities are often obscured by objectification and decorative symbolism. Ballavoine is employing classical portrait conventions even as they are being critiqued within increasingly feminist discourse of the late 19th century. The roses may also connect to symbolic cultural tropes too: beauty, love, womanhood. Curator: So how do you resolve this tension between its artistic execution and its perhaps problematic subject matter, in an era that precedes first-wave feminism? Editor: I think we have to examine that tension, consider what this portrait might tell us about how society constructs and consumes images of women across different points in history. The artist’s process isn't disconnected from the broader socioeconomic structure. Curator: Indeed, analyzing Ballavoine’s technique brings us closer to grasping the historical narrative imbued within his artistic production, and also raises questions of continued gendered representations. Editor: Right, by exploring these issues we bridge a historical art object with the contemporary discourse it intersects. Hopefully sparking awareness of power imbalances in cultural production and beyond.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.