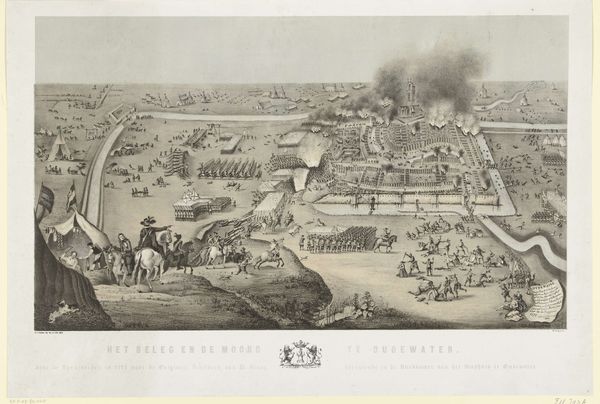

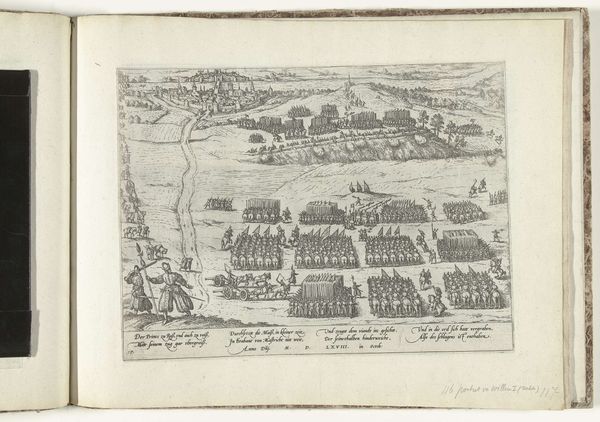

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 130 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

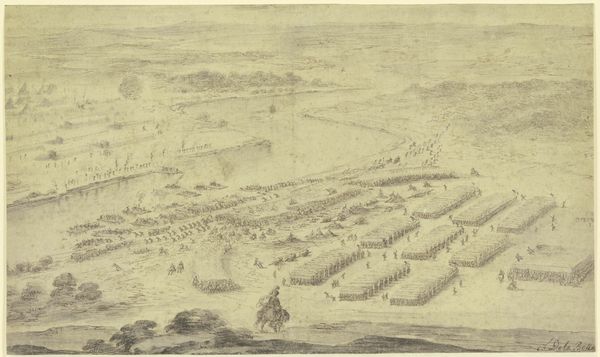

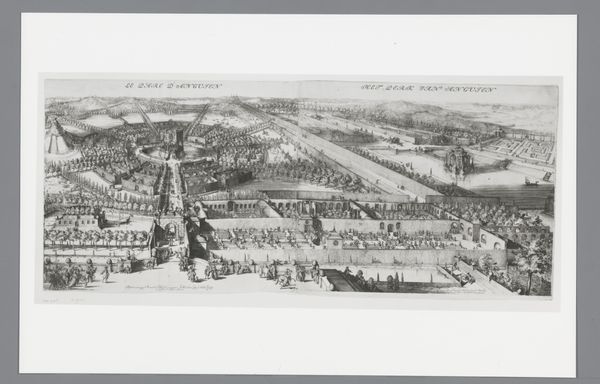

Editor: We're looking at "Schilderij van de plundering van Oudewater, 1575," or "Painting of the looting of Oudewater, 1575," an engraving from 1876 by Eberhard Cornelis Rahms. It looks pretty chaotic and catastrophic, an almost bird's eye view of a city under siege. What can you tell me about this piece? Curator: This image, though created in the 19th century, depicts a crucial moment in Dutch history – the Eighty Years’ War and the struggle for independence from Spain. The sack of Oudewater in 1575 was a brutal event. Consider that "cityscape" and "history painting" are listed in its metadata. I ask you: what ideological stance does this artist take in portraying it this way? Editor: It seems very critical, maybe even condemning. It's hard to glorify violence when you see the destruction of a whole town so clearly. Curator: Exactly. Rahms wasn't just illustrating history; he was participating in a broader discourse about Dutch identity and the trauma of war. These baroque elements could be considered. Think about who might be left out of the story, as well: what perspectives are privileged here? Who benefits from this image, and why? Editor: That's a good point. It’s easy to get caught up in the grand narrative of national struggle and to forget the individual suffering of the people who actually lived through this. Focusing on gender, were the women being taken advantage of during this war, and are they presented here, or are they an unseen presence, invisible victims? Curator: Precisely! It's crucial to recognize the complexities and power dynamics at play in historical representation. Images like these can teach us a great deal about collective memory and the politics of remembrance. Editor: I never thought about it that way; you’re right! This isn't just a picture of a historical event. It's an argument about how we should remember that event, and who we should be remembering. Curator: Precisely! The looting of Oudewater stands as a symbol for later conflicts. Examining it brings fresh nuance and greater depth in how we appreciate visual culture and the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.