photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

realism

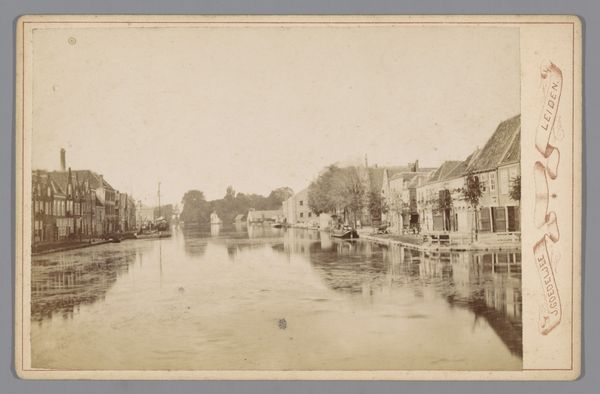

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 153 mm, height 210 mm, width 256 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Overstroming in Nieuwkuijk," or "Flooding in Nieuwkuijk," a photograph from around 1880-1881 by Albert Greiner, housed in the Rijksmuseum. It depicts a flooded town square with people wading through the water. There's an almost ghostly quality to it, with the muted tones and blurred figures. How do you interpret the significance of a photograph like this from a historical perspective? Curator: It's significant because it's not just about aesthetics; it documents a real event, and the effects on a community. Flooding, especially in the Netherlands, was a constant threat and shaped societal structures. Photography like this moves beyond portraiture to illustrate the relationship between environment and the communities adapting to survive there. Consider, what kind of audience was likely viewing photographs like these and how did it shape perception of this sort of landscape event? Editor: I suppose those living in cities, far from these rural areas. Maybe it was meant to garner support for flood relief efforts or highlight the resilience of rural communities. It feels like an early form of photojournalism. Curator: Precisely. These images helped shape public discourse and understanding of both rural and urban realities. Early photography offered the privileged class new access to "faraway" cultures. Realism was thought to give truth. The social implications, of course, were complicated and continue to echo through modern landscape imagery. Thinking about that, how do the "realism" of the photograph's presentation affect what we expect to be true about the image? Editor: It makes it feel like an objective record, but now, I also wonder about the photographer's intentions, what aspects he chose to emphasize or omit, and who had access to see them. I guess even realism is curated, isn't it? Curator: Exactly. That tension between perceived reality and the photographer's agency is what makes studying the history of photography so fascinating. Now how can the way these landscapes are displayed in spaces like Rijksmuseum affect this cultural narrative? Editor: Seeing it in a museum elevates it, I guess. Makes it “Art,” so we contemplate its deeper meanings, beyond just the depicted scene. It makes it a record and historical document worth preserving. Curator: Well, put. Thanks to the flooding captured here, we can ponder about our own cultural moment too. Editor: Indeed, this image sparks discussions about the past but also its continuing influence.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.