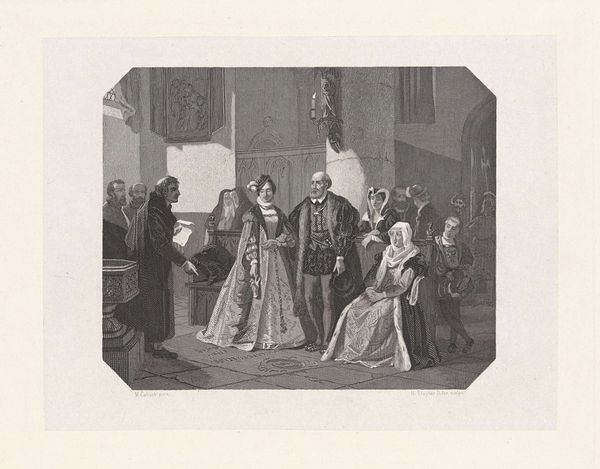

Marriage of Queen Victoria, February 10, 1840 1844

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

group-portraits

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (trimmed within plate): 13 1/2 × 11 1/4 in. (34.3 × 28.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

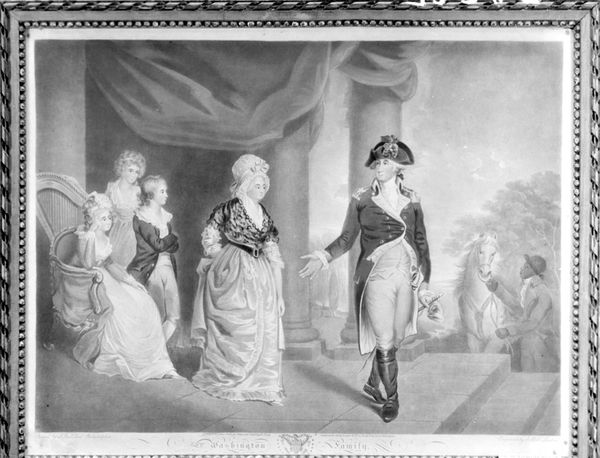

Editor: This engraving from 1844 by Charles Eden Wagstaff is called "Marriage of Queen Victoria, February 10, 1840." The first thing I notice is just how…packed it is. It feels very staged, very formal. What do you make of this scene? Curator: You're right, it is incredibly staged, and that's precisely where its power lies. Consider this not merely as a representation of a wedding, but as a carefully constructed assertion of power and continuity. How does the depiction of Queen Victoria, in particular, strike you in the context of 19th-century gender roles? Editor: Well, she’s positioned as the central figure, literally and figuratively taking the hand of her husband. But she also seems almost…submissive in the way she is portrayed among so many observers. Curator: Exactly. While the image places her at the heart of the monarchy, it also confines her within the patriarchal gaze. Her agency is both emphasized and subtly curtailed by the sheer weight of tradition and expectation. This work speaks to the complex negotiation of female power within a deeply unequal society. Who is she marrying and what did this mean to Great Britain? Editor: She married Prince Albert, so she married for love and duty in her role as head of state. Curator: Precisely, she redefined the monarchy as a family model, setting social trends, as women were expected to marry for love. As a head of state, however, how are colonial subjects represented at the scene of her wedding? Editor: Now that I look again at it...They are completely absent. How can you create an image about a key historical moment by failing to document Britain's presence on so many shores? It strikes me that the romantic presentation masks real power struggles. Curator: It does. The very act of creating this print served to reinforce a specific narrative about nationhood, one that privileged the domestic sphere while erasing the often brutal realities of colonial expansion and exploitation. Food for thought! Editor: Definitely. I’m beginning to see this image less as a straightforward historical record and more as a carefully crafted piece of political theatre.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.