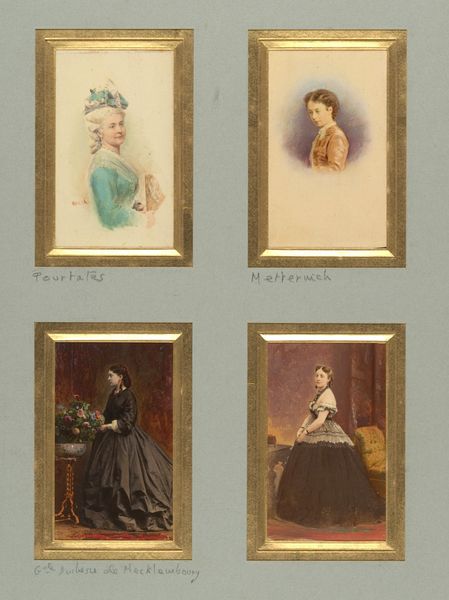

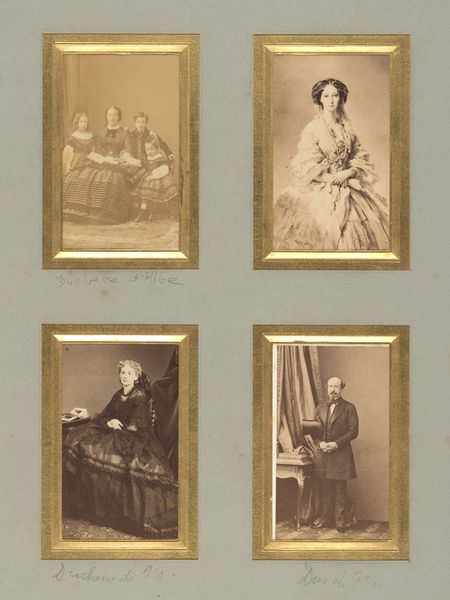

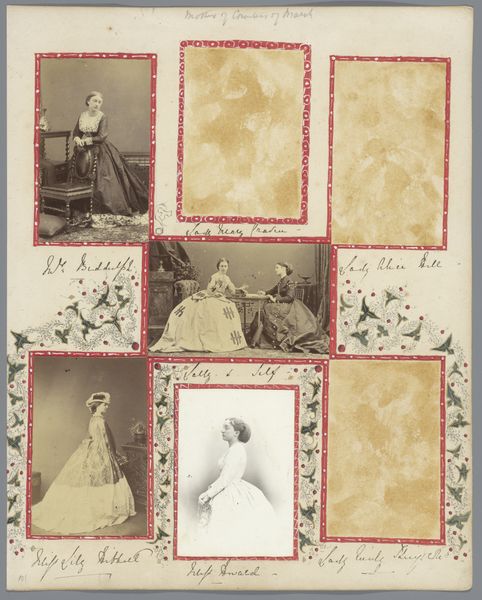

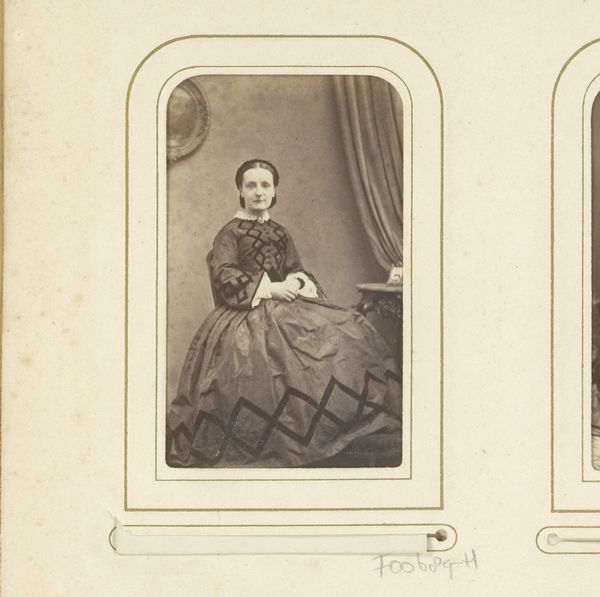

![[Madame Demidoff and Unknown Sitters] by Pierre-Louis Pierson](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzE4ZjY2ZDgzLTM4ZTAtNGRmNi04NWUyLWI0ZGFkMjQ2MzAyZC8xOGY2NmQ4My0zOGUwLTRkZjYtODVlMi1iNGRhZDI0NjMwMmRfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

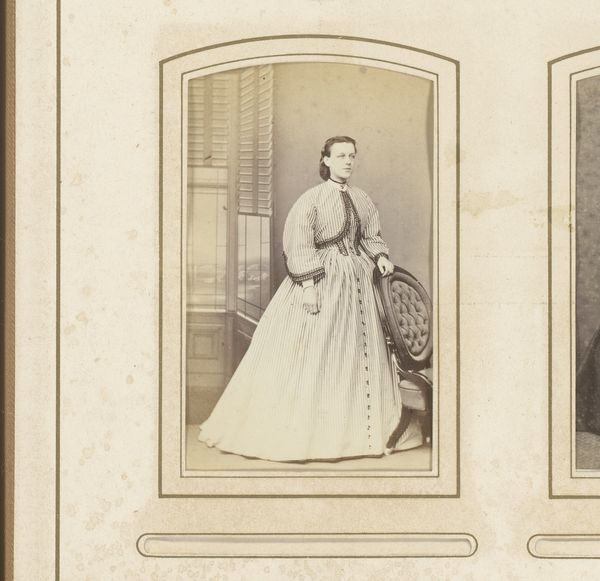

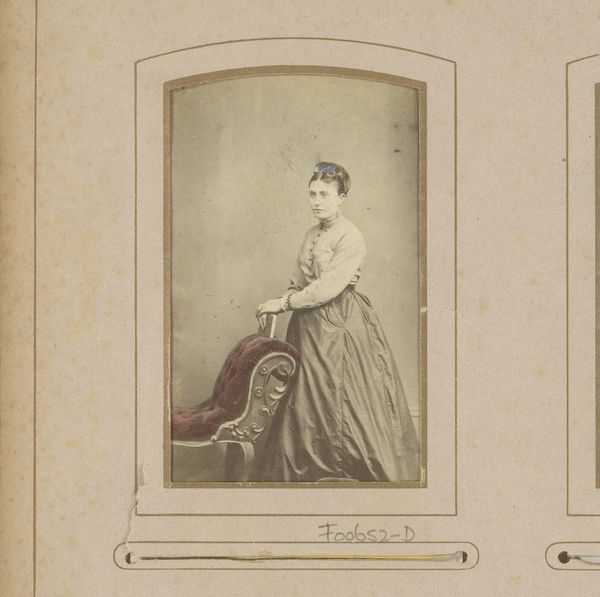

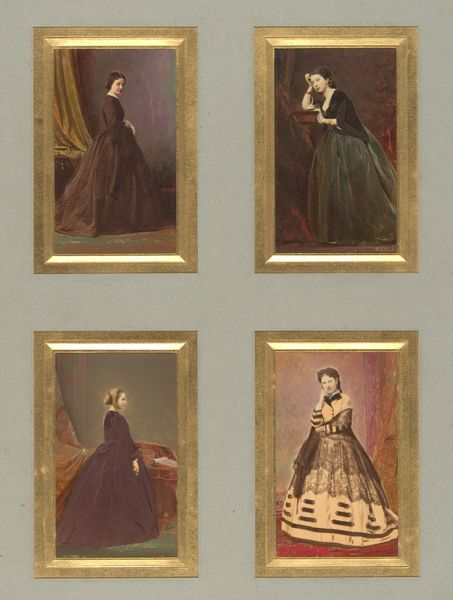

[Madame Demidoff and Unknown Sitters] 1855 - 1865

0:00

0:00

print, photography

#

portrait

# print

#

photography

Dimensions: Image: 3 3/8 in. × 2 in. (8.6 × 5.1 cm) (each)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, we have an intriguing piece titled "[Madame Demidoff and Unknown Sitters]," dating roughly from 1855 to 1865 and attributed to Pierre-Louis Pierson. These photographic prints offer a glimpse into the world of 19th-century portraiture. Editor: Oh, my! My immediate impression is, well, how ghostly the subjects appear. Like little framed apparitions peeking through time, and one's missing! I can’t help but think of abandoned photo albums in antique shops, holding onto fragmented histories. Curator: That’s an apt observation. Photography at this time was still emerging as both an art form and a means of documenting social status. It became a key vehicle in the construction of identity, particularly for women like Madame Demidoff who occupied privileged positions within society. Editor: You're so right. The way these photos are presented – almost like collectible cards or stamps – really underlines the desire to capture, classify, and keep memories, maybe even prestige. The coloring feels deliberately romantic, almost unreal. Curator: Exactly. Pierson's work also highlights the performative aspect of portraiture. Consider the styling and the careful construction of the female image in this era, which intersects deeply with gender studies. It's less about the "real" Madame Demidoff, and more about an idealized version shaped by social expectation. Editor: I find that idea interesting but slightly disturbing. In one photograph the woman appears so young, innocent, like a teenager or someone fresh out of a convent. It’s striking how the lens shapes the viewer's perceptions of female figures. I almost wish that the “Unknown Sitter” would come back, like in a ghost movie, filling out the space that the fourth image creates. Curator: Well, the incompleteness of the group allows the viewer space to wonder, as you do, about those narratives we have now largely lost. Perhaps a comment on how history favors the elite. It asks us to examine absences as part of historical representation. Editor: That resonates profoundly. These images become potent symbols for loss, memory, and forgotten women of history. So few portraits of women that looked like us, or acted like us, remain—and here's a whole grid that refuses to give up secrets. It almost feels…subversive! Curator: A fitting word to conclude our dialogue. I invite our listeners to explore the layered meanings embedded within this photograph, and what it tells us about history, gender and the enduring power of the photographic medium.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.