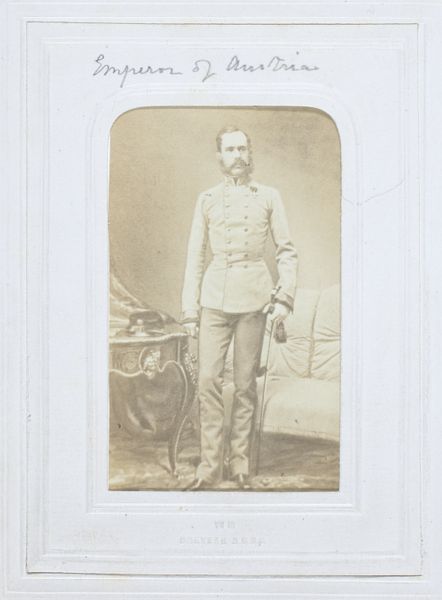

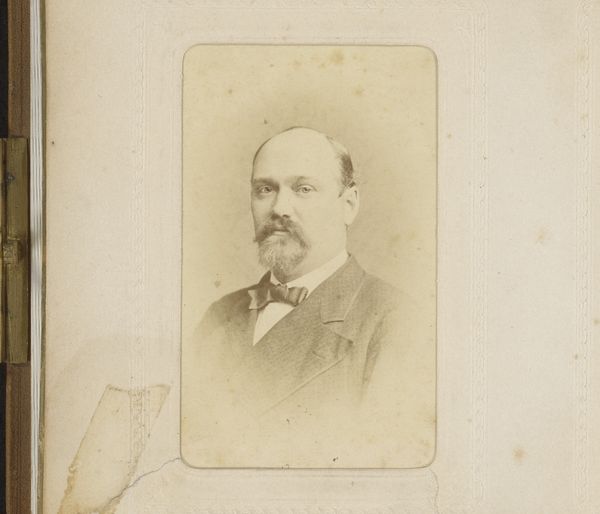

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical fashion

#

19th century

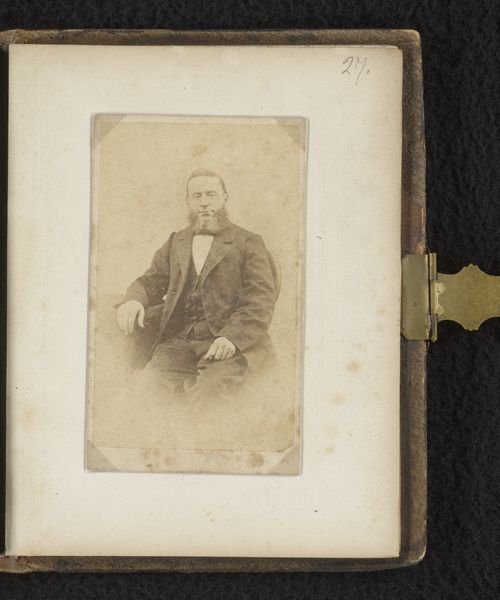

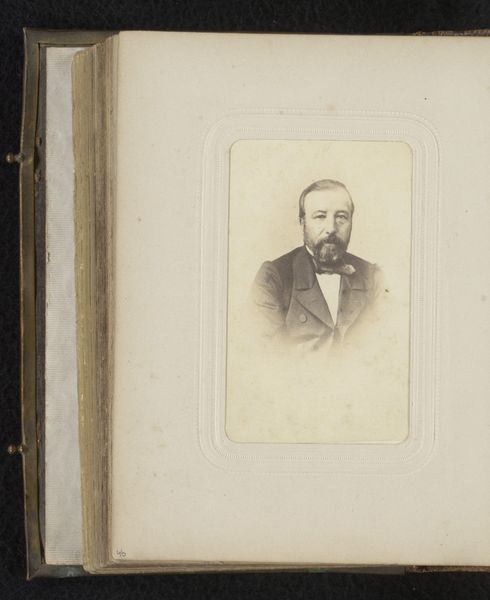

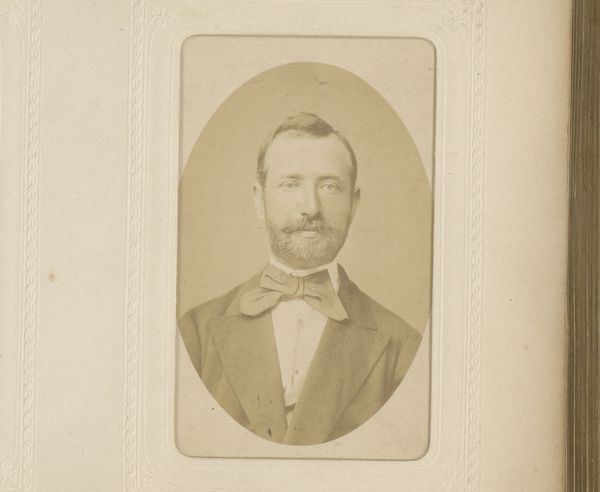

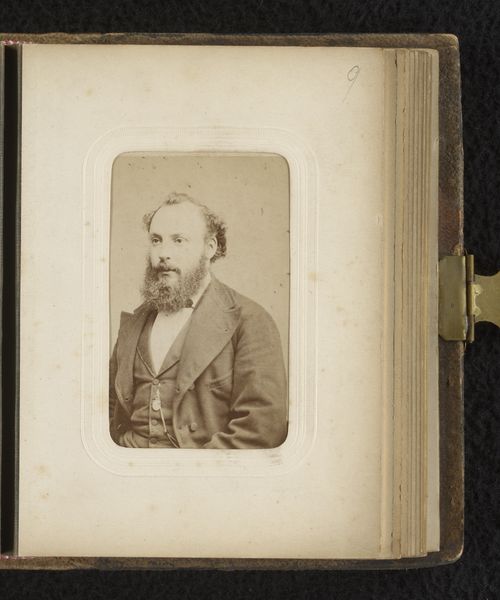

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

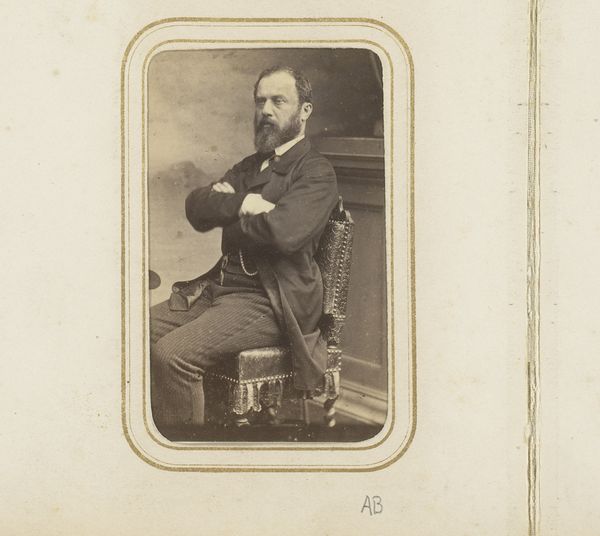

Curator: This is a photographic portrait of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, made sometime between 1870 and 1885. It appears to be a daguerreotype, a very early type of photographic image on silvered copper plate. Editor: It’s striking how small and almost faded it seems. He looks so stiff and formal. Everything is precise—the neatly trimmed beard, the pristine white uniform. There's something a little melancholic about the whole thing, even if he appears regal and composed. Curator: The daguerreotype process does tend to give images a certain ethereal quality, capturing minute detail and delicate tones. Look at the precise depiction of his uniform and the details on his medals and facial hair. The rigidity, though, that's characteristic of the formal portraiture of the time—carefully staged to project authority and strength. Editor: And that very carefully chosen, high-buttoned white uniform evokes military power, doesn’t it? White uniforms often symbolize purity, but here, in the context of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, it reinforces notions of hierarchy and perhaps even untouchability. Franz Joseph's reign was a long and turbulent one, filled with nationalist movements and social change… the image glosses over all the unrest and repression. Curator: Yes, visual culture functioned differently then. Photography was gaining traction, yet paintings continued to reign. These portraits functioned more like standardized symbols than as candid personal insights. Think about the enduring symbols attached to his visage. The trimmed facial hair, which would change through the decades of his rule, were so distinct to Franz Joseph I, yet even now are immediately recognizable and recall particular moments and crises throughout his monarchy. Editor: I see the point about historical symbolism— but, seeing it as an object, too, gives the piece more depth. Think about who created it. We don’t know who the photographer was. They become obscured because it serves the single imperial narrative—that’s just such a contrast to how we create and consume photography now. Curator: True. It reminds us that portraits like this were tools, actively shaping and cementing perceptions. The artistry resides as much in the composition as it does in the process. I now feel a newfound curiosity around the identity of the individual photographer. Editor: For me, I now think about the stories erased by the perfect white uniform and rigid posture, and all the marginalized individuals of the empire.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.