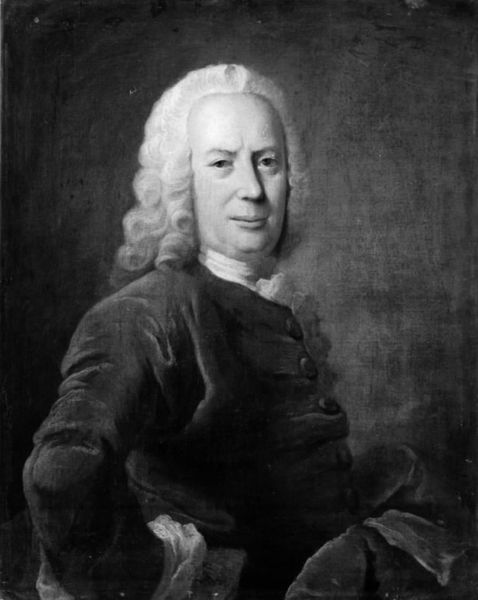

Portrait of Charles Auguste Bourlet de Vauxelles 1768 - 1772

0:00

0:00

oil-paint, canvas

#

portrait

#

low key portrait

#

portrait image

#

portrait

#

oil-paint

#

portrait subject

#

black and white format

#

figuration

#

canvas

#

portrait reference

#

black and white

#

single portrait

#

facial portrait

#

academic-art

#

fine art portrait

#

rococo

Dimensions: 60.5 cm (height) x 49.5 cm (width) (Netto)

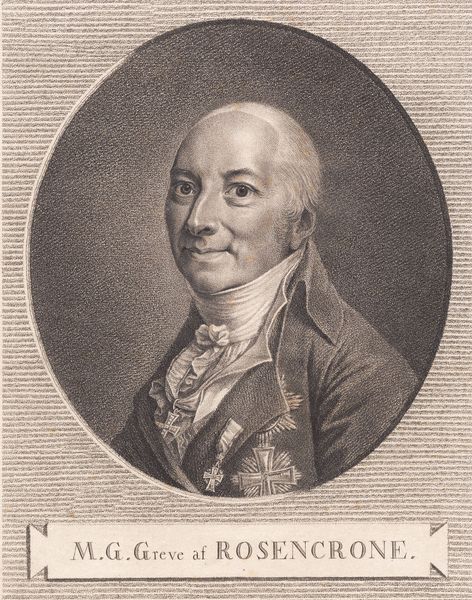

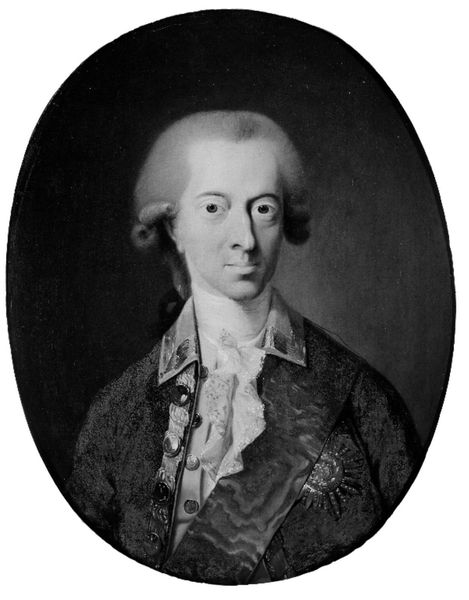

Editor: Standing before us is Alexander Roslin’s “Portrait of Charles Auguste Bourlet de Vauxelles,” created sometime between 1768 and 1772 using oil on canvas. The composition is dominated by an oval portrait, with the sitter looking directly at the viewer. It's such a striking image of a man in powdered wig and fashionable clothing, but what can you tell us about the historical context surrounding this portrait? Curator: It's intriguing, isn't it? Roslin was highly sought after as a portraitist among the European elite. This work reflects the visual language of power prevalent in the late 18th century. Think about the Rococo style, associated with luxury, aristocracy, and a certain… lightness. But does this portrait fit that mold entirely? Editor: Not exactly, the man seems somewhat serious despite his obviously wealthy garments. Curator: Exactly. Portraits during this period were vital tools for constructing identity and reinforcing social hierarchies. They weren't just likenesses; they were carefully constructed performances of status. Bourlet de Vauxelles clearly had the resources to commission such a portrait. But beyond that, what statement do you think he was trying to make about himself and his position within society? Editor: Perhaps he wanted to be remembered, not just for his wealth but for his character. Almost like a gentleman. Curator: Precisely! Think about the rise of Enlightenment ideals alongside the aristocratic culture. There was a tension – a desire for refinement but also a claim to reason and virtue. Consider too where these portraits were displayed – often in the sitter's private residences, used to reinforce their authority to guests, or sometimes in public exhibitions as symbols of cultural power. Editor: That’s fascinating, I never thought about them as such active tools. Curator: Well, the portrait serves as a reminder of the power dynamics embedded in art and its role in shaping how we perceive historical figures. Editor: This makes me reconsider what I assumed I knew about portraits in the past. I see how complex the narrative is that this portrait tells. Thanks so much for clarifying everything.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.