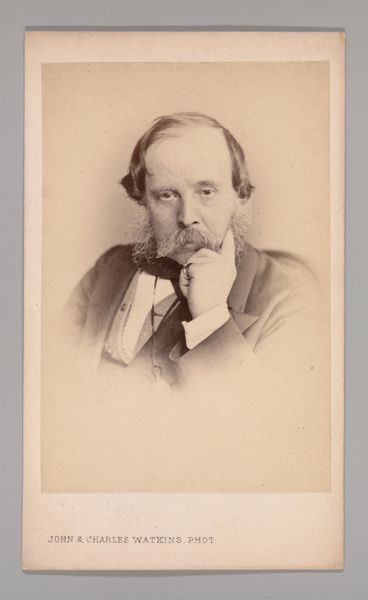

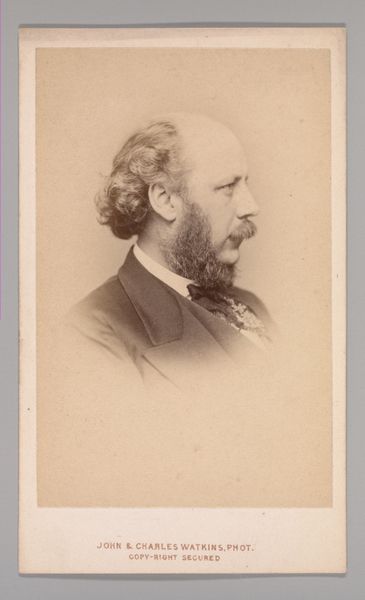

![[William Quiller Orchardson] by John and Charles Watkins](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzE3NWE3Njc2LTI2YzMtNGQ3OC04ZjAzLWE0NmM1OWZkNDc2Ny8xNzVhNzY3Ni0yNmMzLTRkNzgtOGYwMy1hNDZjNTlmZDQ3NjdfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

portrait reference

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: Approx. 10.2 x 6.3 cm (4 x 2 1/2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

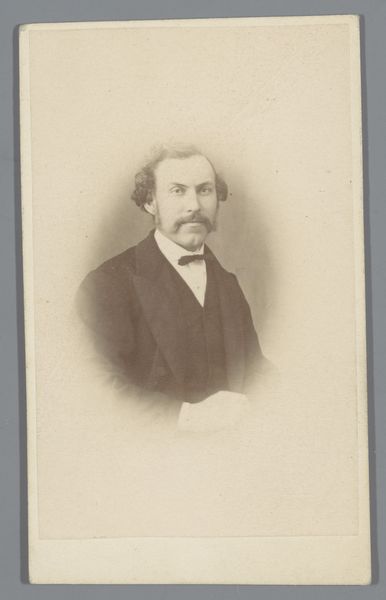

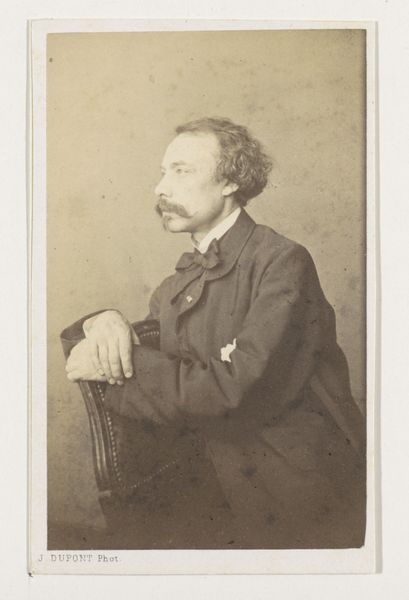

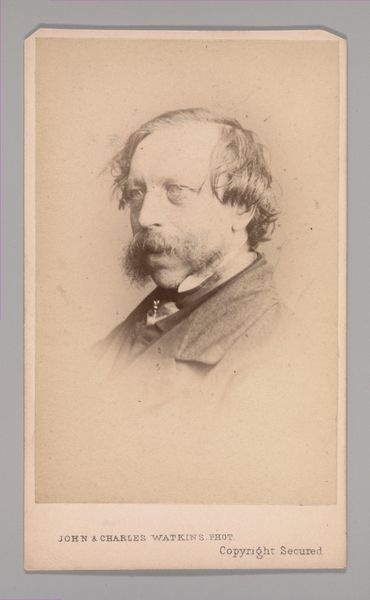

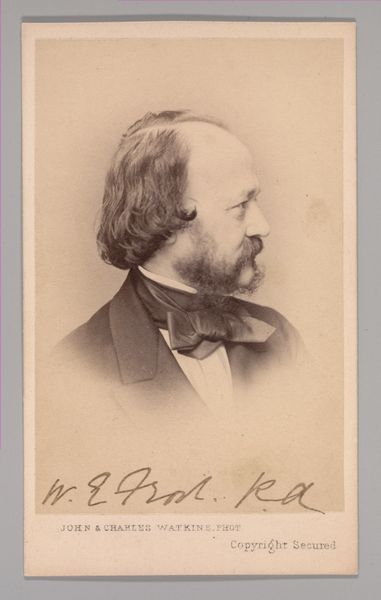

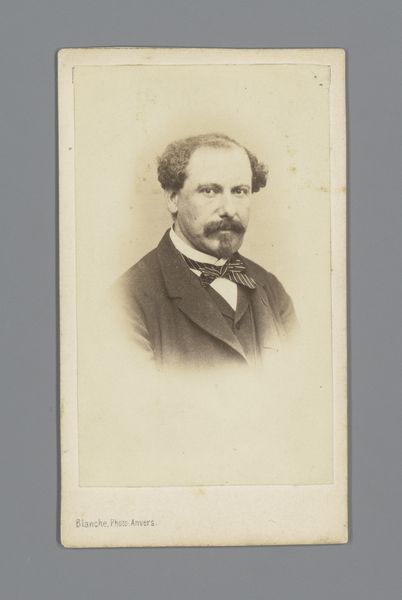

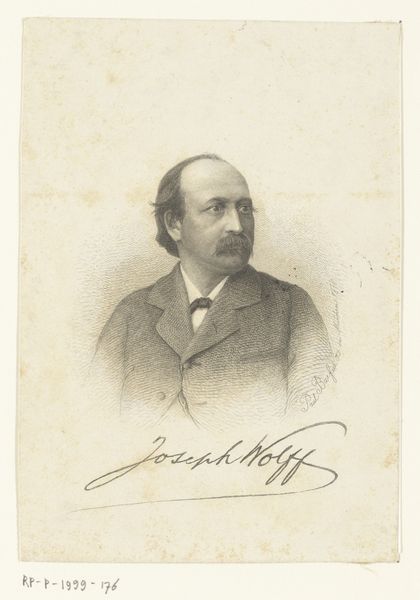

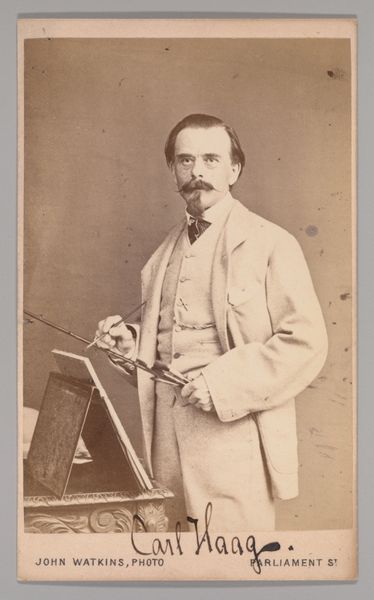

Curator: This striking albumen print captures William Quiller Orchardson in the 1860s. The portrait reference, as it is described, currently resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It has this hauntingly elegant, almost ghostly aura, with the light sepia tones enhancing that feeling. His eyes draw you right in. There's a certain weariness there, but also a kind of restrained intensity. Curator: John and Charles Watkins are the names credited as its photographer. It is presented during the period when photography was emerging as a potent medium for portraiture, challenging the established norms of painted likeness. The style leans towards realism, a direct response to that historical challenge. Editor: And realism here isn’t just about accurate rendering, but about the weight of cultural expectation in that moment. A formal portrait meant projecting a certain persona – respectability, perhaps intelligence, even artistic sensitivity. The mustache especially screams status. It serves as a deliberate proclamation of identity, almost like a visual coat-of-arms. Curator: Absolutely. Portrait photography of this era became a social performance. The subject and photographer actively construct a carefully managed image of status and self. The rise of the middle class drove a demand for these portraits, further popularizing them, making visual distinction paramount, especially for figures in the arts. Editor: But, I wonder if that intensity comes not just from a deliberate construction, but a deeper melancholy tied to his artistic vision. The angle of light makes that contrast, in my opinion. Even a slight droop to his eyes hints at inner struggle and a sort of pensive gaze, don't you think? Or could we be interpreting more emotion into the picture as our own performance as observers? Curator: Interesting point. Certainly, the power of an image lies not just in its creation but in how it continues to be interpreted and re-interpreted across time. By capturing W.Q. Orchardson, the photographers offered society access to a symbol of the mid-19th-century aesthetic. And we in the twenty first century become complicit in interpreting it as more than that. Editor: Perhaps images such as this show us that a single portrait is like a key opening into multiple doors to different, compelling readings about an artist’s journey and society’s values.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.