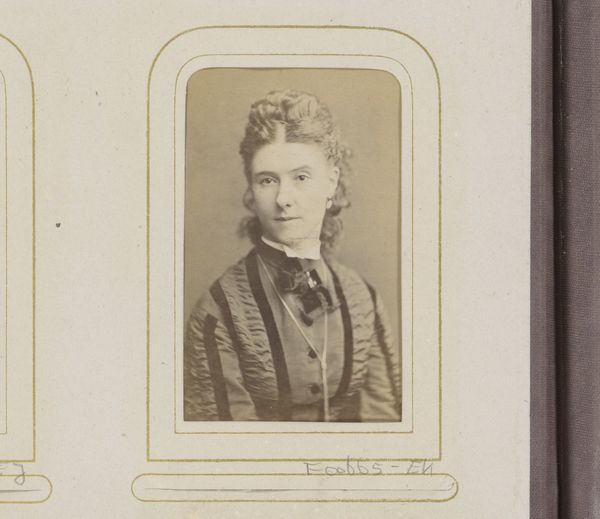

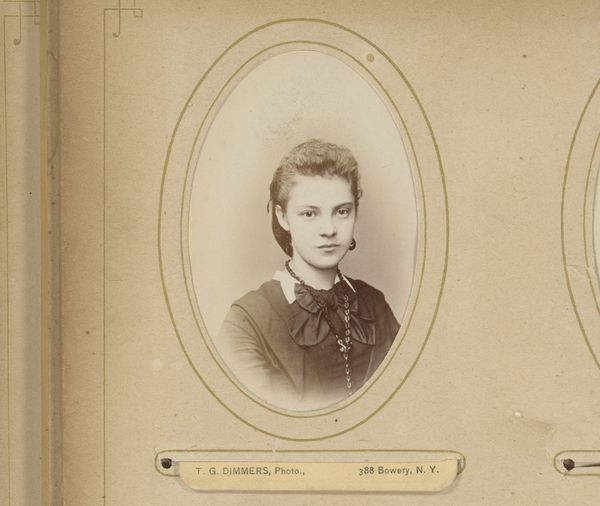

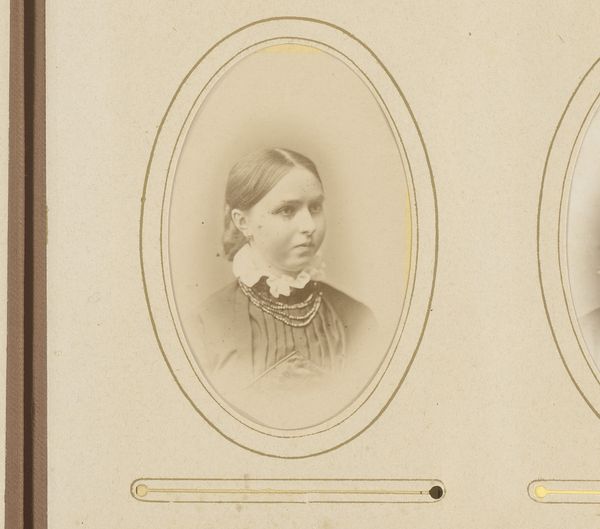

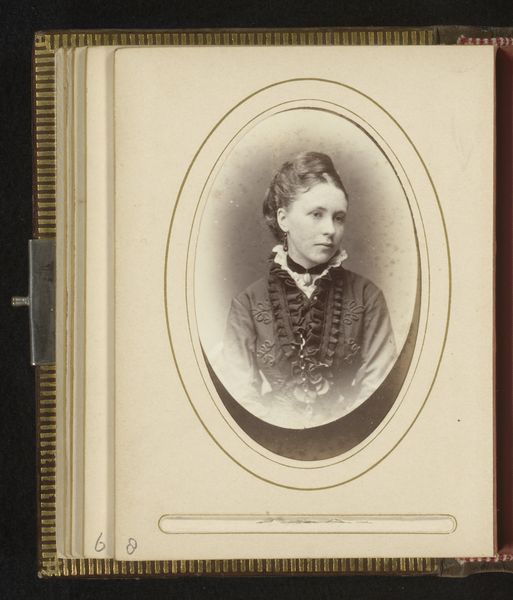

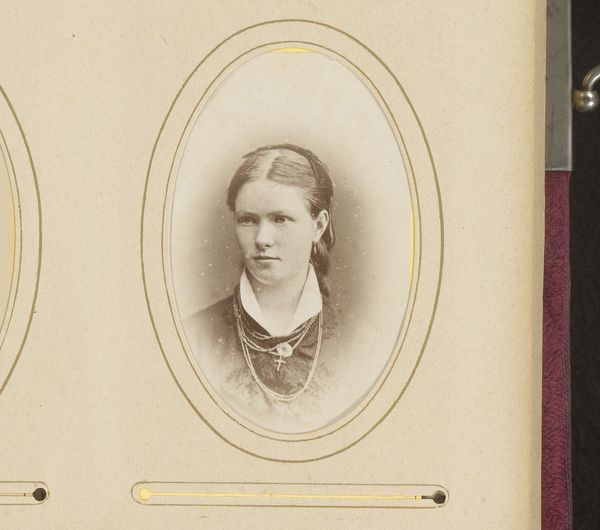

Portret van een jonge vrouw met strik en ketting 1876 - 1900

0:00

0:00

friedrichjuliusvonkolkow

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 81 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a captivating photographic portrait, attributed to Friedrich Julius von Kolkow, titled "Portret van een jonge vrouw met strik en ketting." It's believed to have been created sometime between 1876 and 1900. Editor: There's a beautiful simplicity to it, isn't there? The young woman’s gaze is direct, and I find it somewhat melancholic, perhaps intensified by the sepia tones and the slightly aged quality of the gelatin silver print. Curator: Precisely. The albumen print technique, common during that era, offers a distinctive look—that slightly faded quality and subtle sheen, reflecting the socio-economic shifts influencing photographic processes at the time. Cheaper production became possible at the time photography studios expanded to a broader middle class. Editor: Absolutely. Thinking about it more, what does it mean to 'capture' a young woman in this particular style and context? How does the photograph both reflect and shape the viewer's understanding of femininity, beauty standards, and the objectification inherent in the act of portraiture itself? Especially because the image is titled based on the garments. Curator: That's a very insightful question. The romantic era idealized women, yet the woman presented to us is shown without ornaments besides her ribbon. Von Kolkow likely catered to the aesthetic sensibilities of the late 19th century, reflecting societal values concerning class and virtue. I’m sure many portraits of that era were commissioned for familial display. Editor: Exactly, which raises questions about access, representation, and the very definition of "history" as curated and visualized by certain strata of society. Her look might tell about constraints and the expectation to fill her role in life through marriage, but this we do not know for sure. The photo invites viewers to ask all kind of questions. Curator: Well put. By studying photographs like these, we gain not only insights into past photographic techniques and cultural aesthetics but also open avenues for critical engagement. They're more than just visual records; they’re portals to understanding the socio-political nuances of their time. Editor: I agree. Analyzing how an image performs culturally empowers us to see the invisible narratives that underpin society then and now, while questioning these narratives with a perspective that seeks to create a just society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.