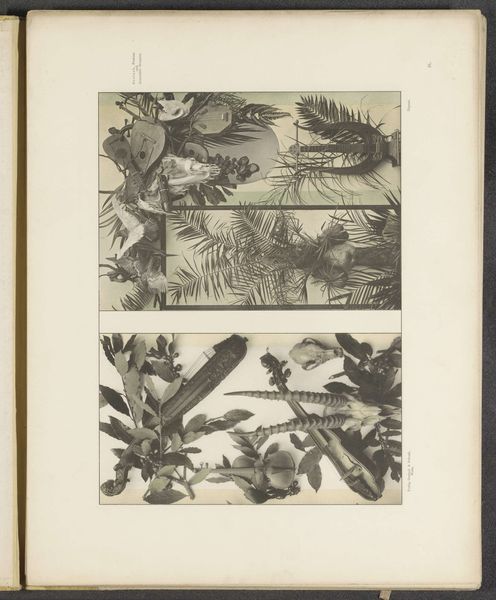

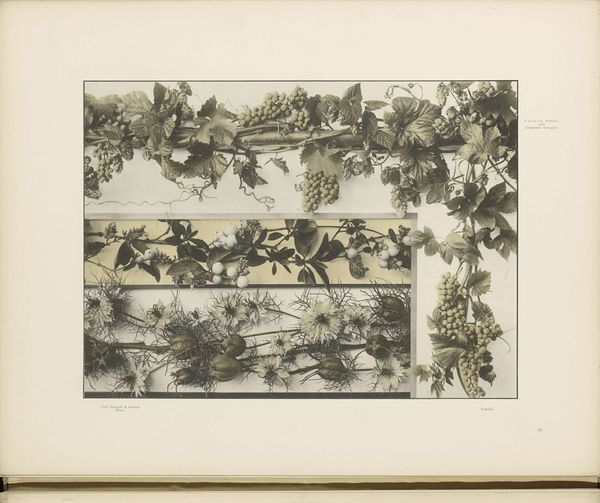

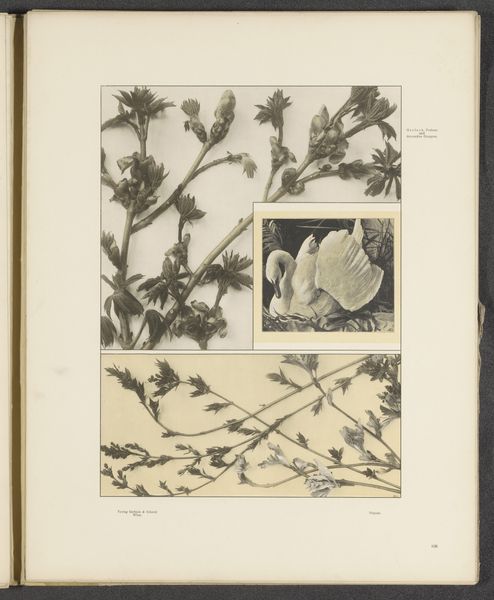

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

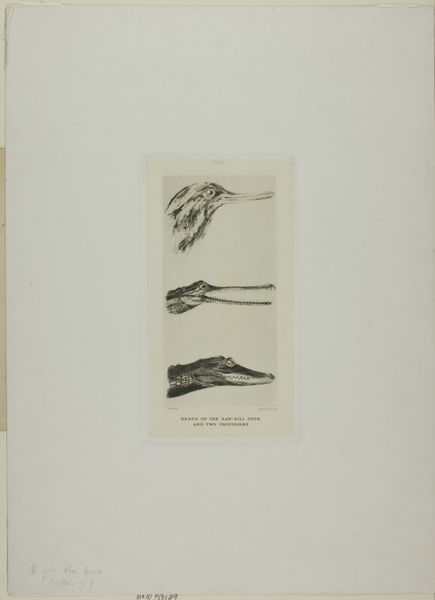

animal

#

pictorialism

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 485 mm, width 612 mm, height 187 mm, width 409 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

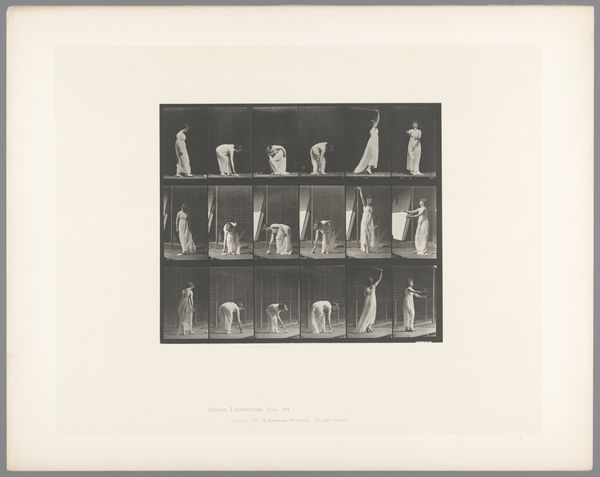

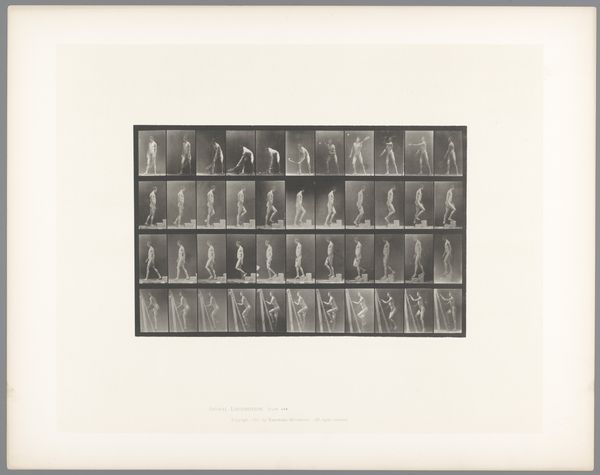

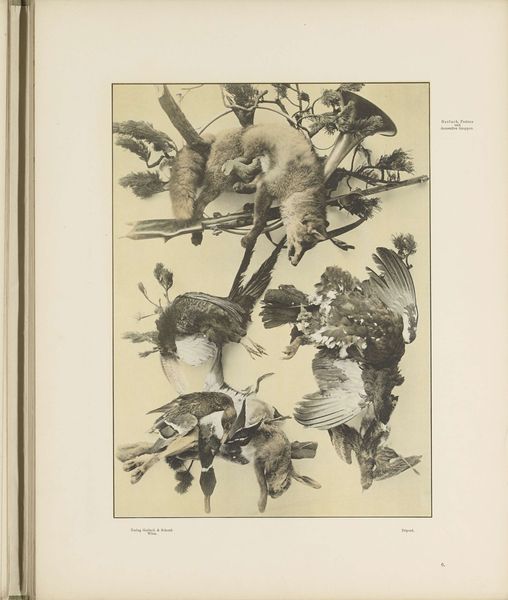

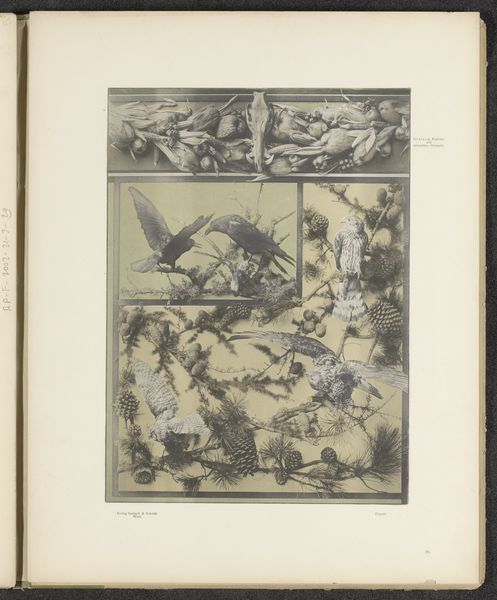

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, “Vulture Flying,” by Eadweard Muybridge, dates to between 1885 and 1886. What strikes you most upon viewing it? Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by its scientific approach; the way the movement is broken down into these discrete moments. It’s like looking at a series of equations describing avian flight. Curator: Absolutely. Muybridge’s work in this period emerged at a fascinating intersection. He captured these sequential photographs to scientifically analyze animal locomotion, driven by questions of visual perception and fueled by both scientific inquiry and debates about animal rights that resonated across different cultural spheres. The vulture, in many traditions, embodies death and rebirth and stands outside what’s considered “beautiful” within Western art history. Editor: I find the limited tonal range, bordering on monochromatic, surprisingly powerful. The grid amplifies this, dissecting not just the movement but our gaze. The stark presentation allows us to study the mechanics of the bird's flight without the distractions of color or conventional pictorial composition. It’s analytical almost to the point of abstraction. Curator: And yet, the individual images betray the technology’s limitations; these photographs offer compelling commentary on how human perception and the camera's "eye" differently render motion, suggesting ideas about objectivity, or perhaps a lack thereof. Vultures, often symbols of ecological health or omens of death and decay, prompt reflections on cycles of life, especially considering late 19th-century environmental degradation. How do these elements work together in your view? Editor: The seriality combined with the subdued grayscale brings to mind the aesthetics of early film, pre-cinema. It highlights how crucial understanding of sequencing is when documenting any kind of movement. If one isolates a single frame, you’ve only captured one piece. But through rigorous arrangement—and viewing from a distance—one sees its unfolding action and its artistry. Curator: Thinking of the work within these frames allows one to realize how critical it is to recognize intersections between the natural world, technological advances, and societal values in the art we consume and discuss. Editor: Indeed. And Muybridge’s almost clinical study here highlights how beauty might not always reside in conventional depictions, but instead within careful examinations.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

While Muybridge initially limited his studies of motion to a horse galloping, he later branched out and experimented with other animals and people. This resulted in the publication of Animal Locomotion in 1887, which included 781 plates of moving horses, elephants, lions, storks, other animals, and people. He had them walk, run, and fly a fixed track, and set up banks of cameras to record their motion.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.