drawing, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

architecture drawing

#

cityscape

#

architecture

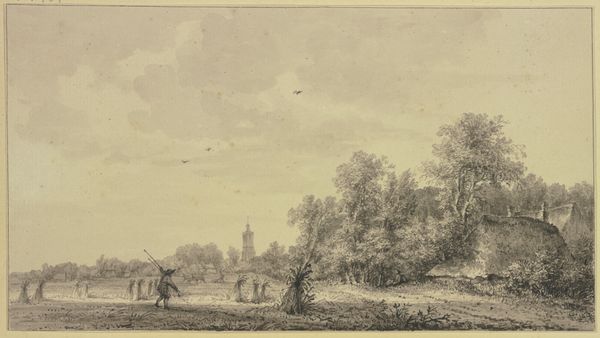

Dimensions: height 348 mm, width 440 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us we have "Landscape with Two Farmhouses and a Church Tower" by Pieter Pietersz. Barbiers, likely created sometime between 1759 and 1842. It’s a drawing, rendered in pencil. Editor: It's a quiet scene. Almost melancholic, wouldn't you say? The soft grays and whites, the slightly sagging roofs—there's a sense of decay, perhaps even the picturesque. Curator: Well, consider the context. Dutch Romanticism often idealized rural life, but not without acknowledging its hardships. This pencil drawing hints at the lives tied to the land. Look at the texture of the thatched roofs; the mark-making itself conveys labor. What pencils were available, what kind of paper was common and how does that play into the imagery? Editor: The drawing itself almost romanticizes that labor, right? Presenting it as gentle, weathered, part of a serene, ordered world even though those thatched roofs represent material struggles and the need for constant repair and the social hierarchy present in rural settings. Note that solitary figure walking in the background. Is it a local person? Curator: Potentially, or a traveler. Think of the materiality of travel at that time. Shoes, roads, accessibility. But the choice of rendering, focusing on form, texture, and structure – even down to the architectural plans of rural buildings-- these elevate everyday craft to fine art. This focus also diminishes any grandstanding about the plight of the labor inherent within it. Editor: Exactly, the scene’s mediated. It gives the viewers something comforting, something familiar, not the gritty truth of life. And a lovely one to contemplate in a public gallery setting like this. Even though you may not be familiar with rural life, there's something nostalgic to grasp onto for modern visitors. Curator: I see your point. It presents an accessible image of agrarian existence for an audience increasingly distanced from such realities. It emphasizes, rather, the materials and construction involved. That's where the dialogue begins between high art and the everyday world, making viewers rethink boundaries and systems of value Editor: Indeed, the dialogue persists, between us, across the centuries, influenced by the art institutions displaying it! Curator: A testament to art's ability to bridge social, cultural, and economic distances.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.