Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

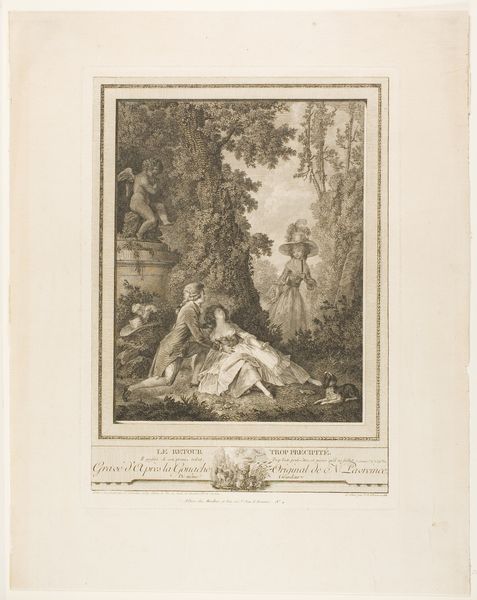

Editor: Here we have an engraving from around 1771 titled "Kneeling Girl Crowned by Amor on a Pedestal." The print shows a woman kneeling before a statue of Cupid, who is placing a floral crown on her head. It strikes me as very dreamlike and ethereal; the landscape feels almost secondary to the figures. How should we interpret this work? Curator: The choice of engraving as a medium is crucial. Note how the meticulous process – the incising of lines into a metal plate, the labor involved in creating the matrix – mimics the very act of adorning the figure with that wreath. The “high art” subject of allegory becomes accessible through the “lower art” of printmaking. This democratizing element is key. The work itself references a cabinet of the Duke, but it is reproduced for consumption. Editor: So you are saying the process itself adds a layer to the piece? Curator: Absolutely. The act of engraving, of meticulous reproduction, comments on the availability and dissemination of imagery. Think about the consumption of luxury items like this engraving within the social context of pre-revolutionary France. How does it reflect on class and access to beauty? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn’t considered the political implications of its reproduction. It's no longer just about the scene depicted, but about who gets to own and experience that image. Curator: Exactly. We can analyze this engraving not just as a static image, but as an artifact within a larger system of production and consumption. Consider also the Duke's cabinet to which the work is assigned, how that cabinet became a symbol of wealth through labor and the employment of artists. The luxury in itself implies the presence of subjugated workers! Editor: I now see the engraving as more than just a pretty image, but a complex object shaped by the labor and social dynamics of its time. Thanks for sharing this perspective! Curator: Likewise. By focusing on materiality and means of production, we can challenge traditional interpretations of art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.