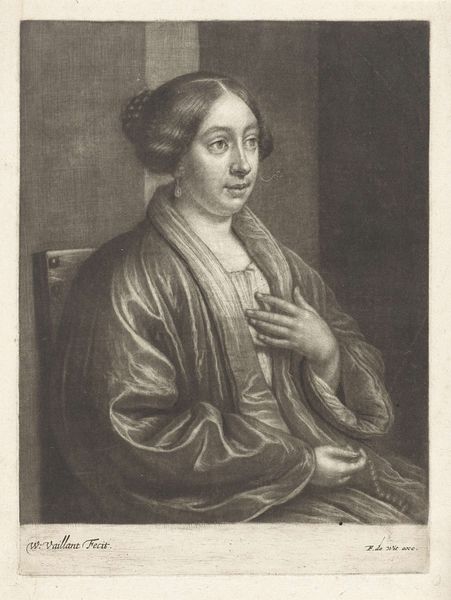

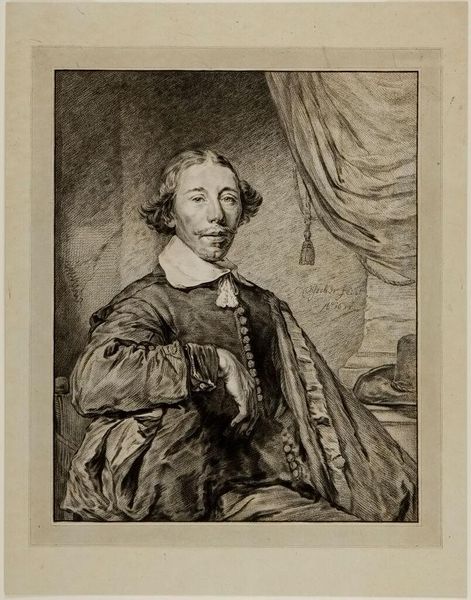

Portret van een vrouw met een parelketting in de hand 1658 - 1677

0:00

0:00

wallerantvaillant

Rijksmuseum

ink, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

ink

#

line

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 261 mm, width 193 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today, we're examining Wallerant Vaillant’s “Portret van een vrouw met een parelketting in de hand," or “Portrait of a Woman with a Pearl Necklace in her Hand,” dating somewhere between 1658 and 1677. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial reaction is to the sheer tactile quality achieved with what I know is an engraving. Look at the heavy folds in that robe, the way light catches those pearl beads! It’s incredibly opulent. Curator: Opulence in printed portraiture served a key social function. These weren’t just images; they were signifiers of status and perhaps even ambition, distributed amongst a social network. Vaillant, as a skilled engraver, was effectively participating in the fashioning and maintenance of social hierarchy. Editor: I see your point about the socio-political implications, but I can't help but focus on the *how*. The technique involved in creating that fabric texture—the specific tools, the sequence of lines etched into the metal—that’s where the magic truly lies. Curator: Absolutely. And consider how a portrait like this facilitated ideas around femininity and domesticity. The pearl necklace and her calm expression speak volumes about the desired virtues in women of the period. Editor: Exactly, the pearls were probably assembled in workshops, requiring various levels of skill in the stringing. The production mirrors the status she displays, reliant on often-unseen labor. I bet a proper material analysis would uncover interesting supply chains, if one could trace the pearls' origins. Curator: Indeed. The image speaks both to the power of networks and global economies—ideas that connect to the larger sphere of Baroque culture and economics of trade and presentation. Editor: I'm left thinking about how each careful score with his tools not only helped produce the "ideal woman," as you call her, but how much sheer physical effort this delicate image involved, linking hand and eye. It speaks to both technical mastery and social structures. Curator: This has definitely reshaped my thinking about it, connecting art with material networks beyond the painter’s workshop. Editor: Mine, too, and also to appreciate engravings and their contribution as producers of early "mass" media through reproducible processes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.