Plate 13: Yellow Swallowtail and Red Admiral Butterflies with a Dragonfly (Broad-Bodied Chaser?) c. 1575 - 1580

0:00

0:00

drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

11_renaissance

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

Dimensions: page size (approximate): 14.3 x 18.4 cm (5 5/8 x 7 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

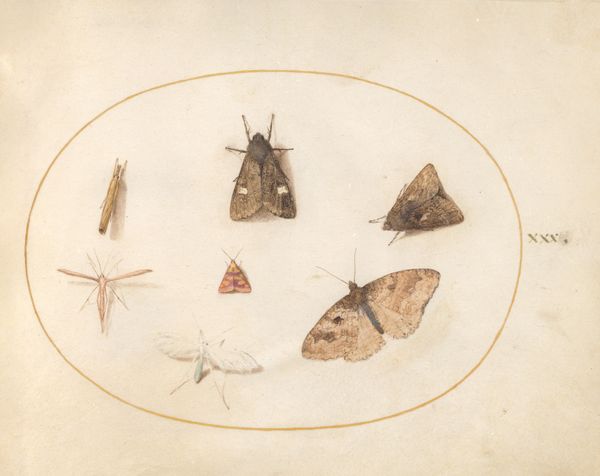

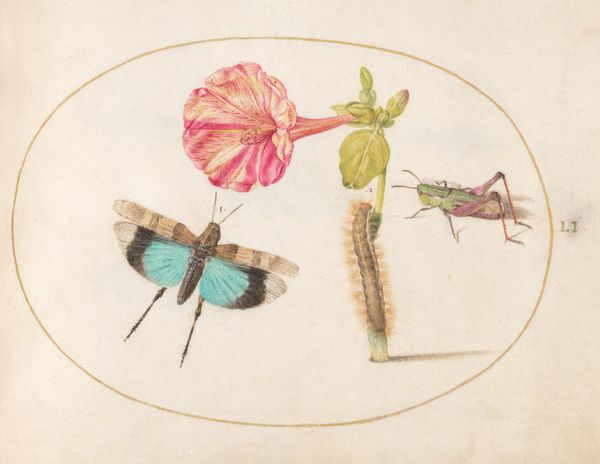

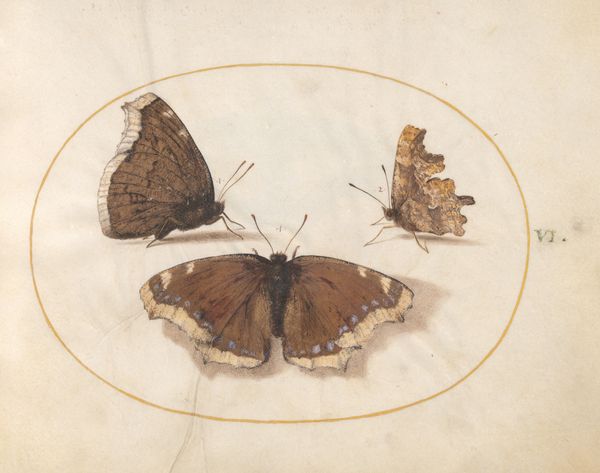

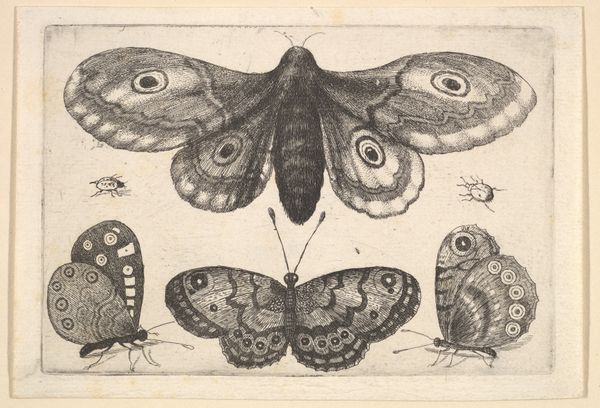

Curator: Up next we have "Plate 13: Yellow Swallowtail and Red Admiral Butterflies with a Dragonfly (Broad-Bodied Chaser?)," created by Joris Hoefnagel circa 1575 to 1580, executed in watercolor. Editor: My first impression is delicacy. The composition, with the careful arrangement of these insects, feels fragile, almost suspended in time. There's an undeniable charm here, like a page from a beautifully illuminated manuscript. Curator: Right, and it's fascinating to consider Hoefnagel's working process. As an artist employed by the Habsburg court, the labor here becomes part of the equation. Each insect is painstakingly rendered. We see the fine hatching used to create texture on the wings, the stippling bringing the bodies to life. Editor: Precisely. These weren't mere illustrations. They reflect a growing scientific curiosity and perhaps, too, a very privileged view of nature. These meticulously documented insects, while visually stunning, remind us about the power structures at play. Who had the resources to commission such works, and what did these images signify for them? Was it a display of scientific prowess, a meditation on the natural world, or simply a reflection of status? Curator: That focus on access is key. Consider the material itself: watercolor. Its transparency allows for layering, creating depth and a remarkable luminosity. It was a demanding medium. Think of the skill required to manage the washes and control the pigment on the paper. Editor: Indeed. I'm curious about the decision to isolate these insects within the oval frame. It elevates them, presenting each creature as a unique specimen worthy of close study and admiration. I’d like to add that within that oval frame we may not be seeing all what went into making these drawings. Are there erased marks, smudges or imperfections in the creation process which are now being erased? And in a society that puts these things forward what does that tell us of beauty ideals and acceptable material? Curator: Definitely, that editing you suggest becomes crucial. This plate exists within a larger cultural context, which includes a developing tradition of scientific illustration and botanical studies. The print was ultimately destined for wealthy collectors who wanted the appearance of an artist without any visual reminder of the struggles to make the works. Editor: Well put. Seeing art through these combined lenses lets us more clearly understand its depth and continued relevance today. Curator: I agree completely. Hopefully, through this discussion, we have inspired new appreciation of what lies behind works such as these drawings.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.