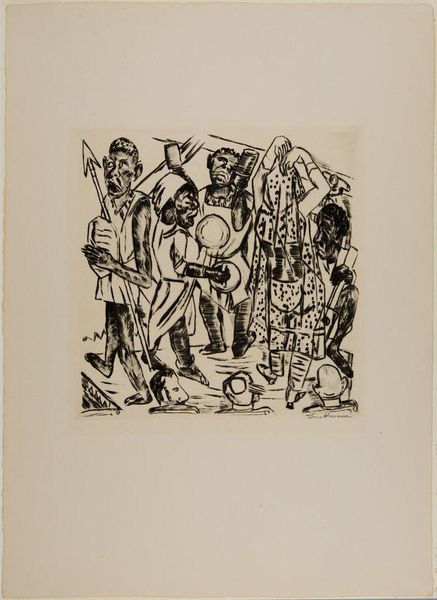

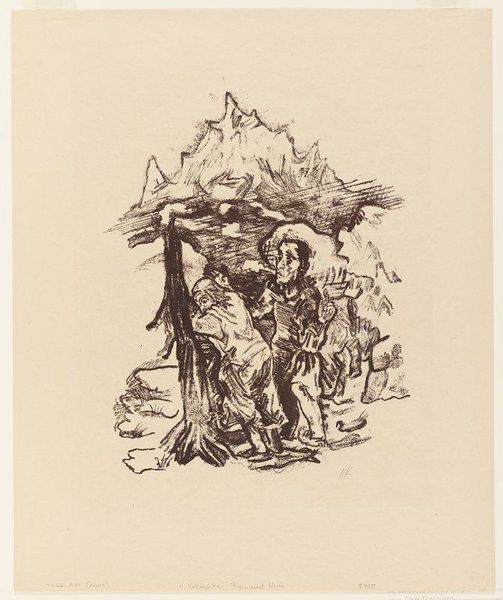

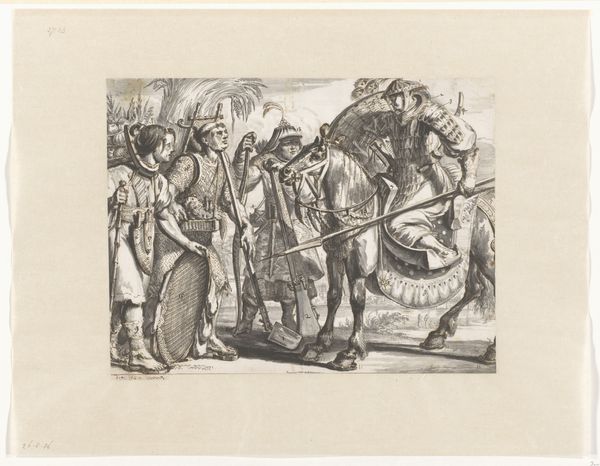

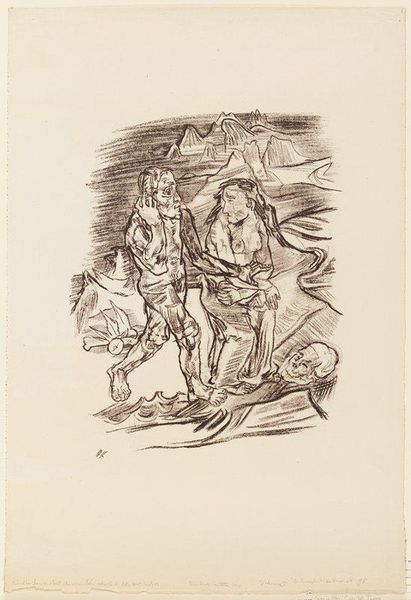

print, drypoint

#

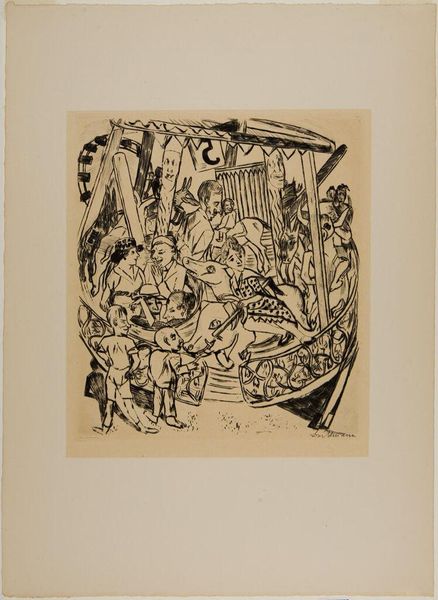

ink drawing

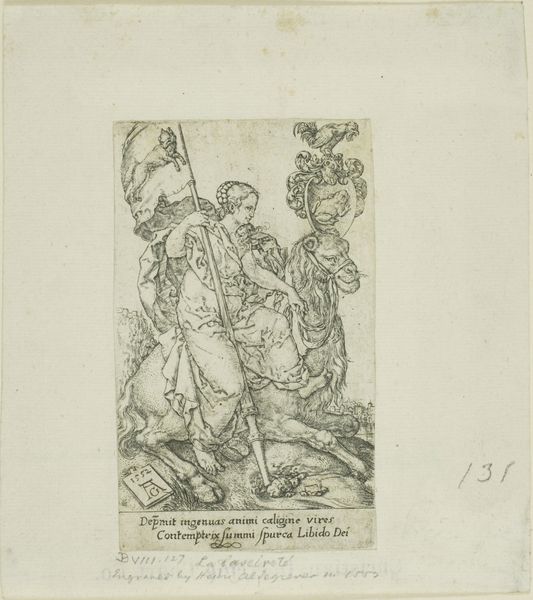

#

narrative-art

#

pen drawing

# print

#

german-expressionism

#

figuration

#

expressionism

#

drypoint

Dimensions: 10 x 10 in. (25.4 x 25.4 cm) (image)14 3/4 x 20 1/2 in. (37.47 x 52.07 cm) (sheet)19 x 15 x 1 1/2 in. (48.26 x 38.1 x 3.81 cm) (outer frame)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

Curator: Looking at Max Beckmann's drypoint, "Negro Dance" from 1921, presently housed in the Minneapolis Institute of Art, I am immediately struck by its raw energy and the sense of a chaotic performance unfolding. Editor: Indeed. There's a primitivism evoked, not only in the overt subject matter, but in the forceful lines and stark contrasts. Considering Beckmann’s wider socio-political engagements after World War I, it reads to me as a complex commentary on societal disruption. Curator: Certainly. The figures, rendered in jagged, angular lines, almost seem to push against the constraints of the print itself. This piece arrives in the period following the war, it is critical to examine it within that period’s context of deep-seated cultural anxiety and its influence in the imagery's construction and public reception. How does it challenge or perpetuate stereotypes that existed then? Editor: Well, that’s where the uncomfortable part lies. While Beckmann’s intentions may have been rooted in exploring perceived 'primitive' energies as a form of social critique – critiquing societal norms of expression and representation, to be exact - the artwork’s title and representation must be analyzed with a sensitivity to how those ideas have been historically wielded to support racist ideologies. The use of ‘Negro’ at the time carries immense baggage, especially coupled with those distorted features. Curator: Absolutely. Furthermore, the deconstructed perspective, with its intentional disruption of typical human form and distortion of spatial relations, can be analyzed as a subversive stance. It makes me consider, does the artwork ultimately empower the people it features, or does it risk further marginalizing them, cementing an 'otherness' by a dominating Western eye? Editor: A vital point. And it leads us to reflect on the politics of spectatorship as well. How has this piece been contextualized in different eras, and how do those frameworks change the interpretation? Even displaying such a piece in a modern gallery prompts this important dialog of ethical engagement. Curator: Indeed, the act of exhibiting is itself a claim to importance; a suggestion for what the viewer must take away. To look at Beckmann's choices as separate from their consequences—art historically 'excusing' possible intentions or aesthetic interests separate from ethics and implications—would be to risk endorsing the harmful stereotypes being communicated to an unsuspecting public. Editor: A sober reflection for our listeners to hold as they move through the exhibit and view “Negro Dance,” and a clear demonstration of the responsibilities that arise when interpreting such art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.