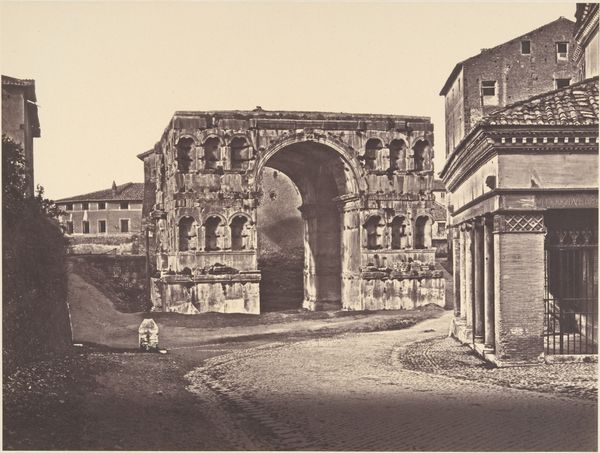

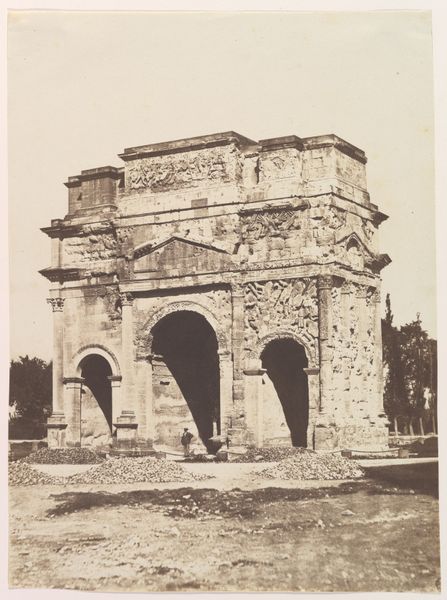

daguerreotype, photography, architecture

#

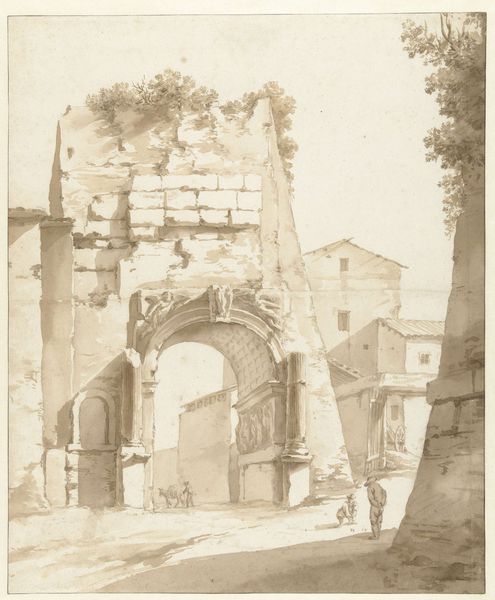

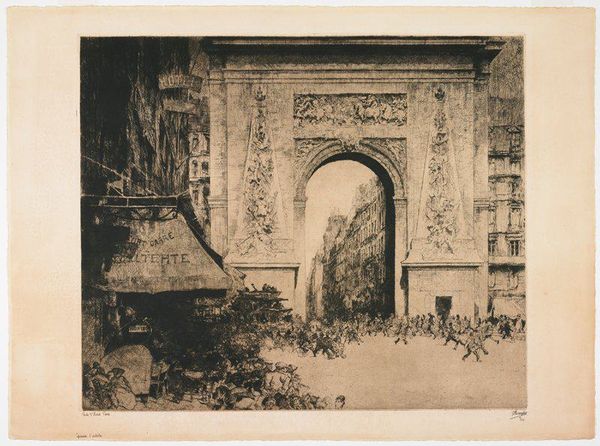

neoclacissism

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

cityscape

#

architecture

Dimensions: Image: 6 7/16 × 8 7/16 in. (16.4 × 21.5 cm) Sheet: 12 1/8 × 18 1/2 in. (30.8 × 47 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, we're looking at Eugène Constant's "Arco di Tito," a daguerreotype made between 1848 and 1852. The sepia tones and the clarity of the arch are striking. It really brings home the grandeur of Roman architecture, but also the inevitable decay. How do you interpret this work, especially thinking about when it was made? Curator: It's fascinating to consider this daguerreotype within the context of its production. Photography in the mid-19th century became a powerful tool, not only for documentation but also for shaping perceptions of history and culture. Capturing the Arch of Titus at this time speaks to a growing fascination with classical antiquity and its influence on contemporary European identity. This arch, of course, commemorates a military victory... How does Constant’s image address the public's imagination regarding Rome and the empire's cultural influence? Editor: Well, it feels almost… archaeological. Like we're observing a ruin, but also appreciating the endurance of this Roman symbol. The angle really emphasizes the worn stone and almost minimizes the people, it's not as populated and lively as other cityscapes I've seen from this era, focusing more on what is ancient. Curator: Exactly. Constant isn't just documenting a landmark. He's presenting a visual argument about Rome’s continued relevance to a 19th-century audience steeped in Neoclassical ideals. Consider how the Daguerreotype itself, a new technology, lends an aura of scientific objectivity to the scene. It creates the illusion of unmediated access to the past. How might that have shaped the viewer’s understanding of Roman history versus, say, an earlier painting of the same site? Editor: I hadn't thought of that "illusion of objectivity." A painting might romanticize it, whereas the photograph almost certifies its realness and... I suppose its historical importance by extension. That gives me a new angle on 19th-century landscape photography. Curator: Indeed. It's not simply a record; it's an active participant in shaping historical narratives and, perhaps more insidiously, solidifying specific cultural values around that history. The daguerreotype aimed to both archive the architecture of a space and contribute to the dialogue of Rome as both ruin and source for Western Art. Editor: I see. Looking at this with the knowledge of the daguerreotype's role is illuminating! Thanks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.