photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

portrait reference

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

realism

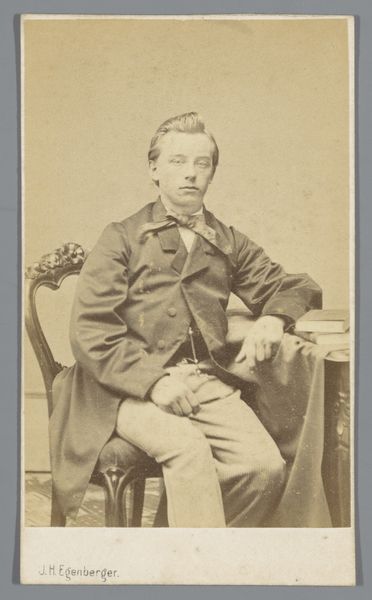

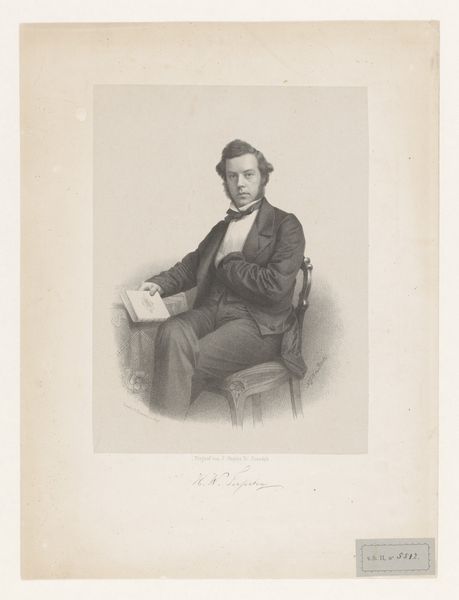

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

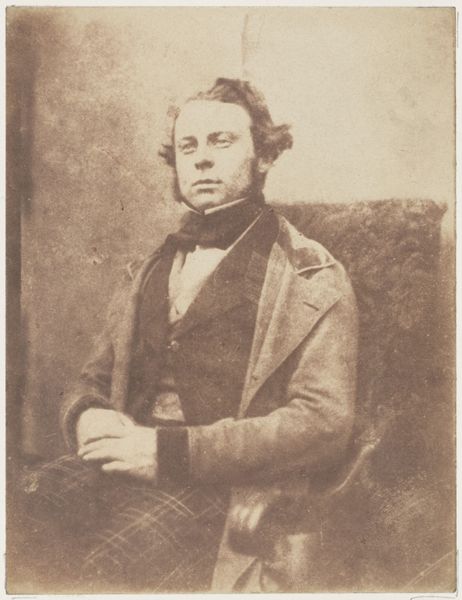

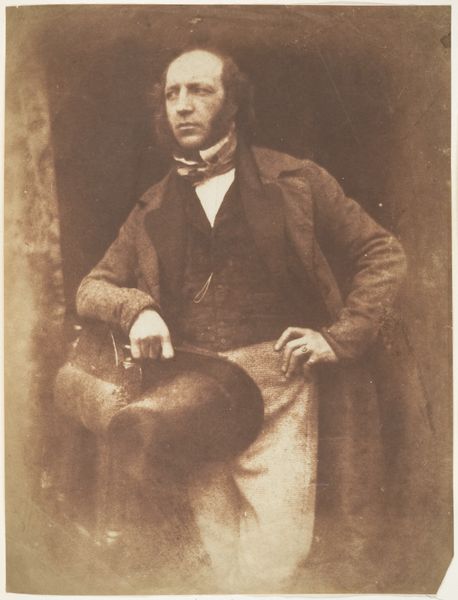

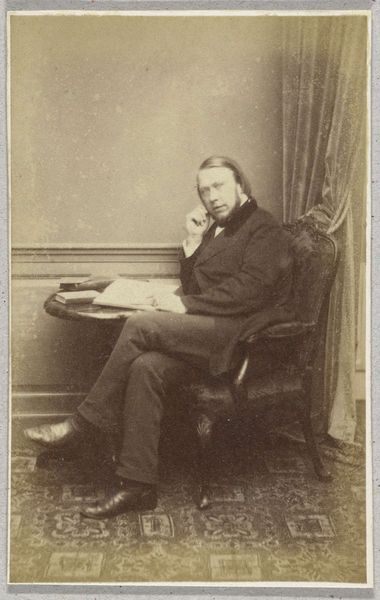

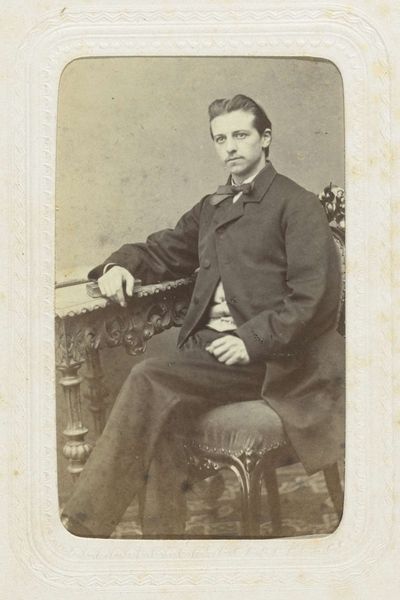

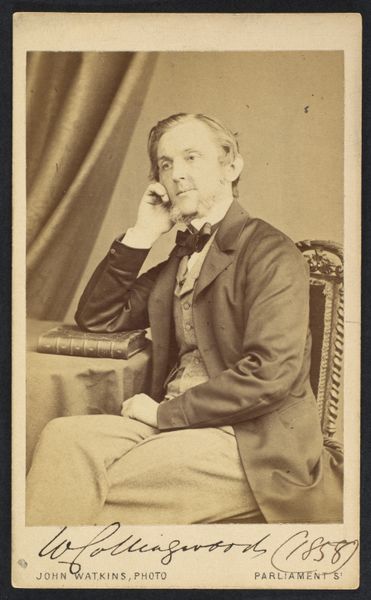

Curator: Looking at this gelatin silver print from the Rijksmuseum's collection, “Portret van een man met een strik en een jas,” made sometime between 1855 and 1889 by Franz Wilhelm Deutmann, I’m struck by how formal yet intimate it feels. What's your immediate impression? Editor: Somber, almost…melancholy? The sitter's expression coupled with the muted tones gives off a vibe that makes me think about the strict conventions of the time and the perhaps suffocating roles prescribed to men. Curator: Absolutely. The photographic portrait became increasingly popular in the mid-19th century. Its availability opened portraiture to the middle class, a powerful shift from earlier periods when painted portraits were reserved for the elite. It became almost a societal rite of passage. Editor: It’s fascinating how these portraits codified particular performances of masculinity, too. Note the formal attire, the subdued posture. Photography was still quite novel; how did these norms influence society's perception and representation of the self? Was there room for people to exist outside of them? Curator: Precisely. Consider the controlled gaze and careful posing. Early photographic studios offered a very public space for identity construction. They dictated the acceptable forms, essentially, democratizing representation while simultaneously policing it. This image speaks volumes about the institutionalized presentation of self that was gaining momentum at the time. Editor: I think it’s also important to highlight how access was still heavily mediated by race, class, and even physical ability. While cheaper than painting, getting your portrait taken was still a marker of privilege, subtly excluding and othering those who couldn't afford or navigate the system. Curator: That's a critical point. The archive of these early photos isn't neutral. It's full of cultural assumptions about who mattered, and it’s vital to continually challenge these assumptions when we engage with historical images like this one. Editor: Examining the photograph from today's vantage point is to grapple with both its documentary function and its complex implications. We cannot detach historical work from contemporary sociopolitical discourse about gender, representation, and power. It asks important questions, and doesn't necessarily offer a resolution, which, ultimately, is probably its strength. Curator: And a key role museums play now, bringing art out from its contextual past and inserting into contemporary critical dialogues to find fresh angles from which we can appreciate the image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.