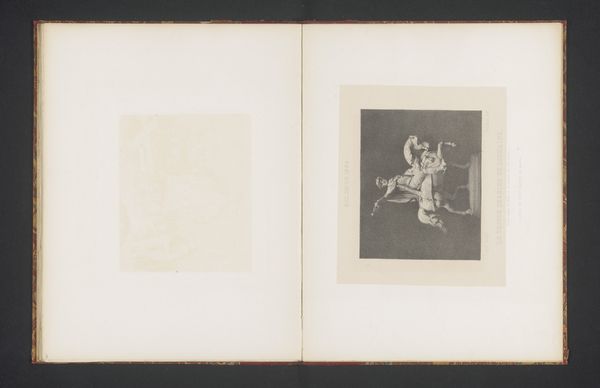

Fotoreproductie van de Kruisiging van Christus door Anthony van Dyck before 1861

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 366 mm, width 253 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a photograph titled "Fotoreproductie van de Kruisiging van Christus door Anthony van Dyck," attributed to Edmond Fierlants. Though created before 1861, the photograph captures Van Dyck’s baroque painting style through the relatively new medium of photography. Editor: It’s a stark image, isn’t it? The gelatin-silver print process renders it almost monochromatic, intensifying the subject's pain. I'm struck by how such suffering becomes an aesthetic object within our modern viewing context. Curator: Absolutely. Placing the print in its historical context is important. Photography in the 19th century revolutionized the accessibility of art. Reproductions like this allowed the masses to engage with masterworks. However, they also raise complex questions about authenticity and commodification. How does such a graphic depiction circulate within the popular culture of its time? Editor: It prompts a question about how violence against the body is consumed and perhaps even normalized, through art. And particularly, violence against *this* body, which is historically coded male and white. How do viewers' own social locations—their race, gender, class—affect their interpretation of such imagery? Curator: These prints were also crucial for art historical study. They democratized visual information for scholars and artists, circulating imagery more rapidly than engravings. But as you mentioned, it brings the historical problem of violence back into the conversation about the history of art and reproduction. Editor: Considering the composition itself—Christ’s figure dominates the space. I see echoes of patriarchal structures and the continued veneration, even idealization, of male suffering within certain narratives. It demands interrogation. The history and power relations within the church are all implicated in this. Curator: Indeed. A study of patronage in the period in which Van Dyck made the painting would allow for analysis of how the political role of religious imagery worked through these depictions and continue through today. This print acts as an artifact withstanding that transformation over time. Editor: Looking at this reproduction makes me wonder what kind of response it generated among groups whose experiences were completely excluded from, and often directly opposed by, these dominant cultural narratives. It makes you realize the artwork isn't just a snapshot in history, but part of an ongoing conversation about faith, power, and representation. Curator: I concur entirely. Thanks for sharing your incisive perspectives, it adds many interesting considerations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.