Medal commemorating the Capture of Valencia in Italy (La Prise de Valence en Italie) 1685 - 1695

0:00

0:00

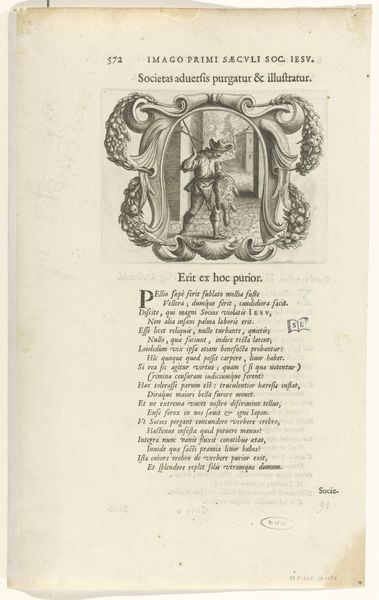

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

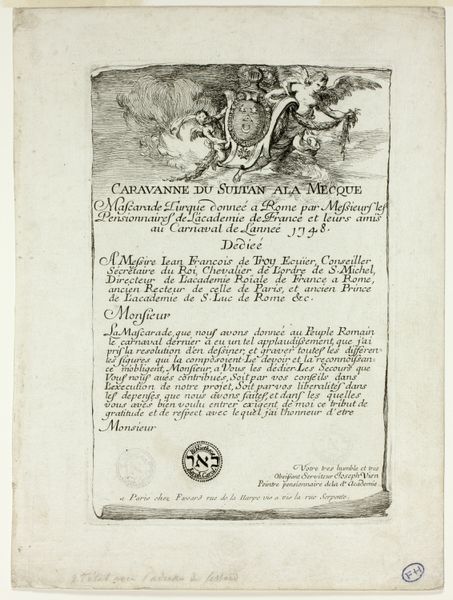

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

paper

#

text

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Image: 12 9/16 x 8 1/4 in. (31.9 x 21 cm) Plate: 12 11/16 x 8 7/16 in. (32.3 x 21.4 cm) Sheet: 17 1/16 x 11 5/16 in. (43.3 x 28.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

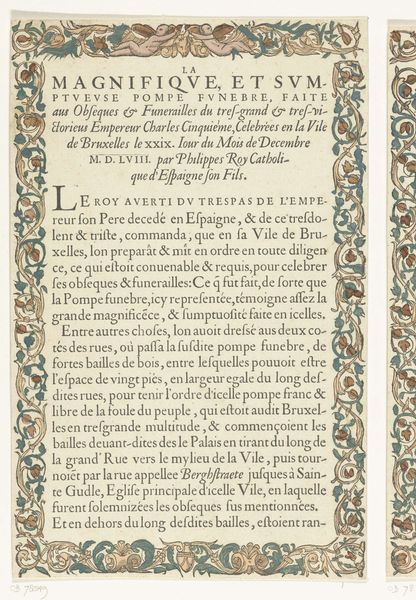

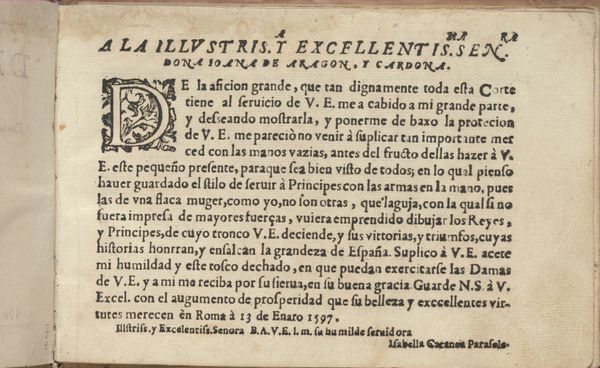

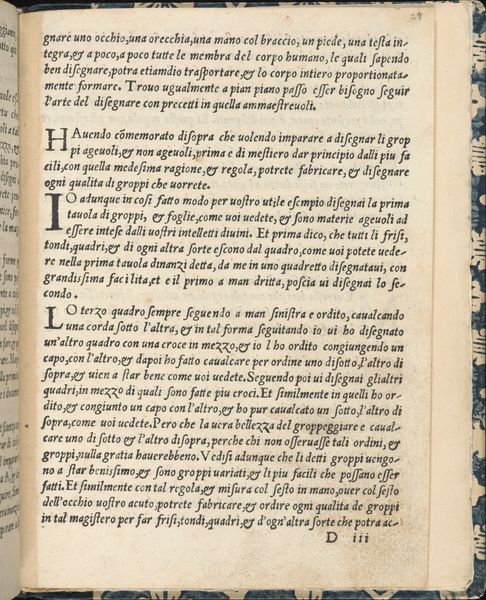

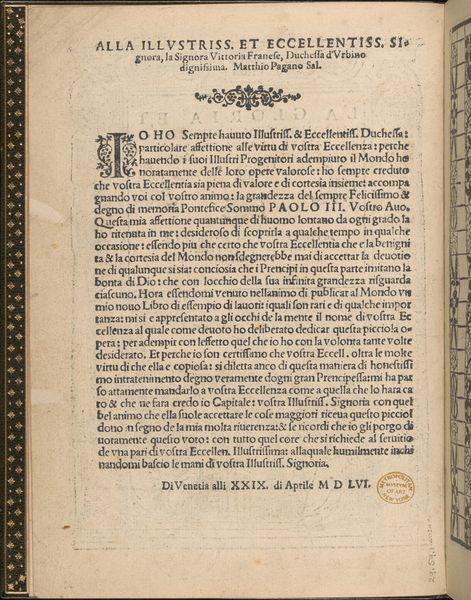

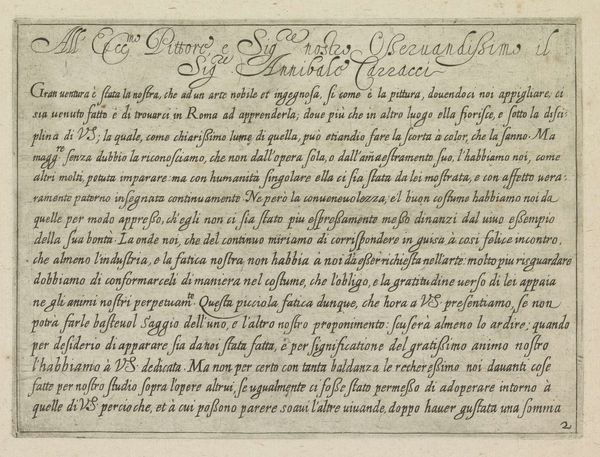

Curator: I'd like to draw our attention to this print, "Medal commemorating the Capture of Valencia in Italy," crafted sometime between 1685 and 1695. It’s currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The engraving work is attributed to Louis Simonneau. Editor: My first impression is that this feels very self-consciously grand, even performative in its visual language. Is it meant to serve as a straightforward historical document? Curator: Not quite. It operates on several levels, including propaganda. What appears to be a straightforward commemoration also subtly reinforces French power during that period. Look at the imagery around the central text, which provides an account of the siege itself. Editor: Yes, I notice the medals depicted above. One bears a portrait – presumably Louis XIV – while the other showcases an allegorical figure of France triumphing over a defeated Spain, “Valentia ad Padum vi capta” – Valencia captured by force on the Po river. Classic Baroque triumphalism. I see France planting its flag. Spain lays defeated underneath it. Curator: Exactly. It blends a detailed recounting of events with potent symbols and idealized representations. France embodies strength and justified conquest. Editor: I am wondering, what's the target audience? And was the goal to educate or to simply impress, inspire national pride, perhaps? Curator: It was likely targeted towards the French court and upper classes—to circulate and reinforce Louis XIV’s image as a powerful and divinely ordained ruler. The inscription certainly would have reinforced nationalistic sentiments, turning a localized victory into something of major cultural significance. Editor: And do you think such symbolic language still resonates? Can a contemporary audience decode these loaded images and phrases, or have they largely lost their punch? Curator: I think the core idea still carries weight: Nations commemorate and often aggrandize their victories. Perhaps, we've become more aware of how narratives are constructed to serve certain political ends, but the power of such symbols persists in collective memory. Editor: Indeed. Examining this piece provides a crucial window into the ways power and propaganda intersected centuries ago—lessons relevant for any age grappling with its own symbols of authority.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.