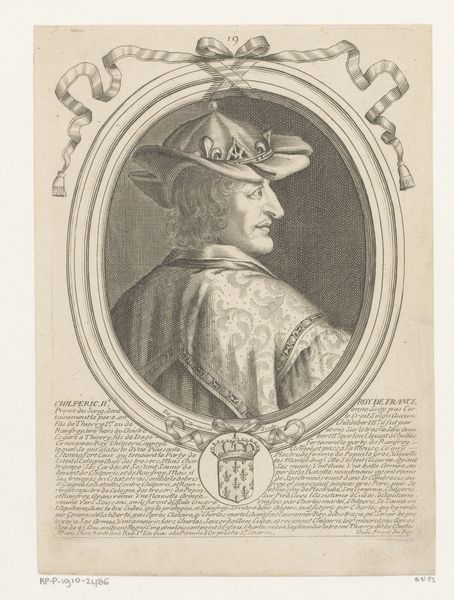

Dimensions: height 402 mm, width 270 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: My first impression is one of quiet dignity. There’s a certain formality in his posture and expression. Editor: Exactly. That gravity feels appropriate given that this is a portrait of Ahmed Resmî Efendi, dating back to 1764, rendered through an engraving. Curator: The stone archway he's framed by adds to that feeling. It’s like we are looking at him through a window into the past, a carefully constructed barrier. Is that arch symbolically relevant? Editor: Absolutely. In the 18th century, portraits served as crucial documents of cultural exchange, especially when depicting diplomats and figures of authority like Resmî Efendi. Here, he's memorialized not merely as an individual, but as a historical bridge between the Ottoman Empire and Europe. Curator: He's holding what appears to be a document… rolled, almost like a scroll. It suggests his occupation, of course, but the scroll form feels significant somehow. Editor: That's right. Holding what looks like a treaty or important decree is definitely a signal to his profession as a diplomat and envoy. Engravings such as this were often commissioned to commemorate diplomatic missions and cement international relations visually. The linear precision and clarity speaks volumes of the Enlightenment values prized at that time. Curator: The layering of textures is intriguing – the fur trim on his robe against the smoothness of the stone, for instance. Those textures communicate more than just material richness, though. Editor: Definitely. The artist uses line quality, which you identified, and textures to build a cultural narrative. Look closer, too, at the blend of Islamic artistic styles within the text alongside what are arguably more Baroque approaches. This intersection reflects not just an artistic choice, but an active cultural dialogue. Curator: Looking at the detail, the clothing does hold so much significance and power here. Even his headdress is making a visual claim to the man’s standing. How might period viewers receive those signals in his portrait? Editor: His sartorial elements would have carried weight, presenting both identity and power, signifying both authority and an "exotic" otherness to its European audience, reinforcing perceptions—sometimes quite political—of the Ottoman Empire at the time. This work invites discussions about cultural projection and self-representation. Curator: A complex, compelling historical artifact then… and now. Thanks for your insightful observations. Editor: The pleasure was all mine. Thinking about it now, portraits like these urge us to explore not just what we see but *how* socio-cultural contexts influence visual depictions across centuries.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.