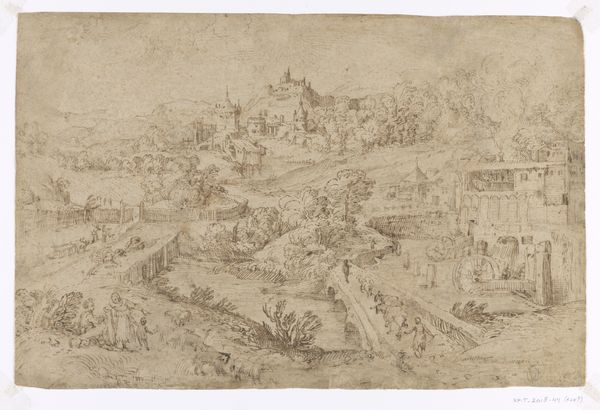

drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

#

romanticism

Dimensions: sheet: 34 x 46.5 cm (13 3/8 x 18 5/16 in.) image: 33 x 45.6 cm (13 x 17 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: It's remarkable how much narrative detail Joseph Anton Koch packs into this relatively small ink drawing. Tivoli and the Waterfalls with Shepherd Families, from 1821, depicts exactly what the title promises, yet there's so much more happening here. Editor: My immediate sense is one of idealized peace, a kind of Arcadian fantasy. The figures seem at ease within this meticulously rendered landscape. Almost too picturesque to be real. Curator: The Tivoli waterfalls themselves are key. The setting of Tivoli near Rome held particular significance for Romantic artists. They saw it as a place where unspoiled nature coexisted with the ruins of classical antiquity. Koch is placing his figures in a location layered with historical and mythological weight. Editor: Yes, I notice how the falls are positioned to cascade almost directly behind the resting shepherd families. It's as if nature’s force is blessing, or at least overshadowing, the figures. It does prompt us to wonder about the relationship between humans and the overwhelming forces of the natural world, something frequently explored in Romanticism. Curator: And consider the shepherd families themselves. Their placement suggests a return to simpler values, contrasting the corruption of urban life with pastoral virtue. Think of them as symbols, perhaps, for an escape from industrial progress and its discontents, a yearning reflected throughout much of 19th-century art. The family units and the dog connote familiarity and perhaps safety. Editor: Looking closer, there’s something deliberately classical about the way the figures are posed, referencing conventions used to depict ancient deities and nymphs. But their rustic clothing and activity reminds me that Koch might be evoking history to make contemporary social points. Who gets to live an idyllic life, and what is their connection to the land and society at large? Curator: It certainly speaks to a very specific historical longing, a desire for a more authentic, connected existence. But, I also appreciate it purely as a window into the picturesque tourism that grew in popularity around this time, showing the landscape as it was often consumed by affluent Europeans. Editor: Ultimately, this drawing, like many landscapes of the period, reveals not only a physical space but also an intellectual space—one shaped by nostalgia, critique, and an ongoing debate about modernity and its impact on the human spirit.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.