Dimensions: plate: 23.02 × 26.35 cm (9 1/16 × 10 3/8 in.) sheet: 31.43 × 35.24 cm (12 3/8 × 13 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

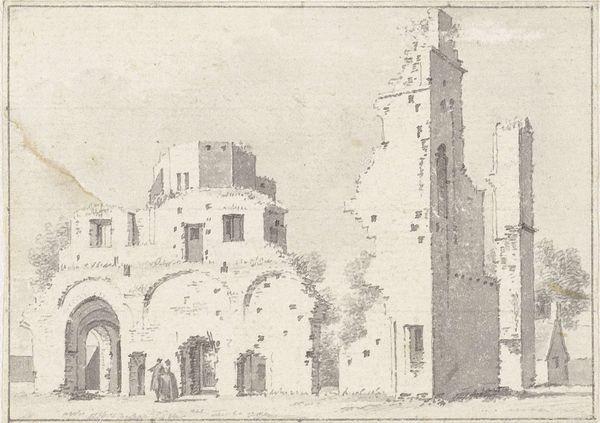

Curator: Looking at Charles J. Watson's etching, Saint Germain, L'Auxerrois, created in 1913, I’m immediately struck by the sheer level of detail achieved through this printmaking technique. The building almost appears to be breathing, alive with its architectural energy. What stands out to you? Editor: The overwhelming feeling I get is one of profound liminality. Here's a building of grand history, caught in a state of repair and transformation. There are people walking around and congregating but their class or socio-economic background are hard to pin down; they don’t feel completely connected to either its historical or modern context. It makes me think about social stratification and access to resources. Curator: I agree. There is the visual evidence of labour through scaffolding, offering a stark contrast to the detailed craftsmanship etched into the building's facade. It draws our attention to the labour involved in maintaining these spaces of supposed reverence and cultural importance. Editor: Exactly. It's the materiality of that process that’s particularly engaging; consider the relationship between manual labour of construction workers and the art objects it produces: churches that function, or that don't, depending on funding or patronage or, more basically, materials! Then, there’s this tension between decay and preservation. Who decides what gets saved? Curator: Thinking about materials further, Watson has rendered a monumental structure using the delicate process of etching. There is a stark duality in technique as related to architectural subject, where a single slip of the etcher's needle can irreparably change the image. What statement do you think Watson is trying to make by emphasizing labor through the process of creating the etching? Editor: That is such a keen observation! Perhaps it underscores the inherent inequalities in visibility. The skilled labor that creates and sustains culture often remains unseen, their stories untold. It’s that power dynamic—who gets to tell the story and whose contributions are erased or appropriated that sits at the center. Curator: Ultimately, it compels me to look deeper, considering not just the grandeur of the church but the lives and work that support it. Editor: For me, it's a call to critically engage with our cultural inheritance, interrogating whose histories and realities are privileged in our public spaces and in our art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.