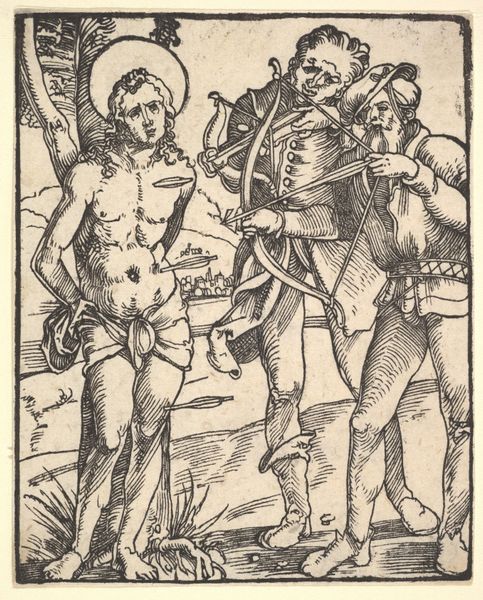

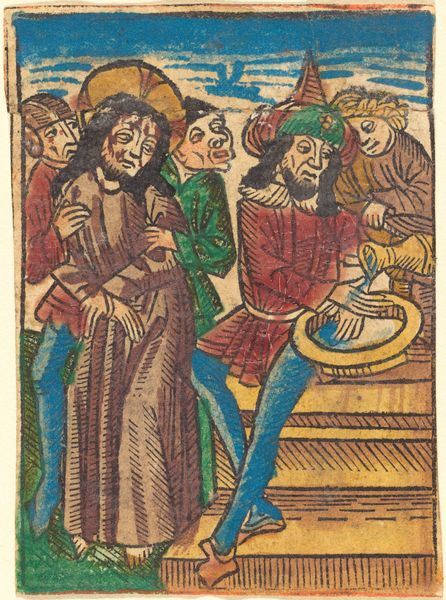

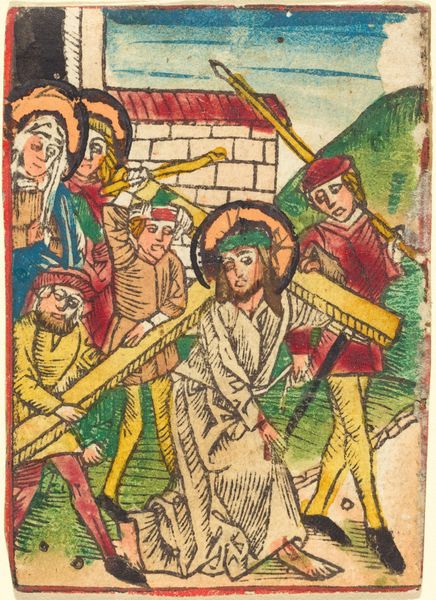

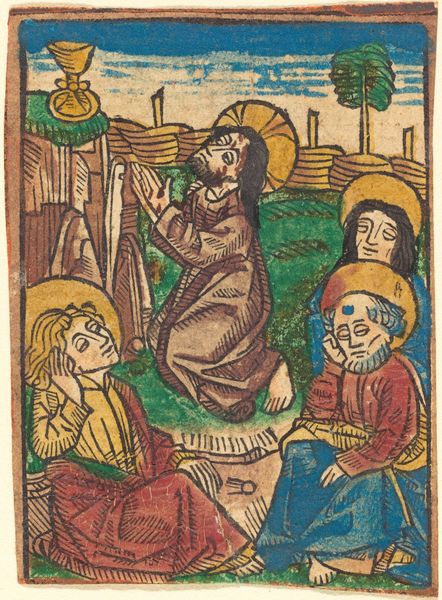

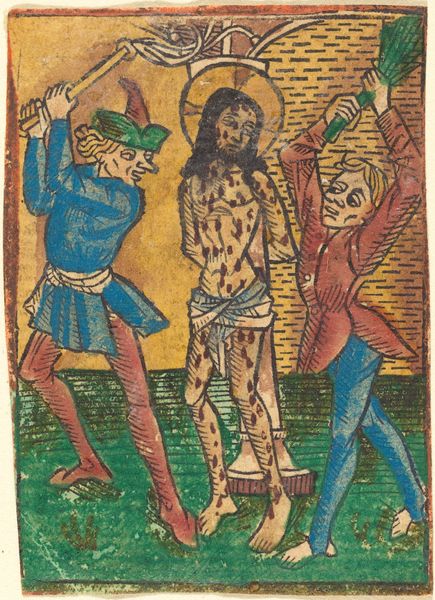

print, woodcut

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

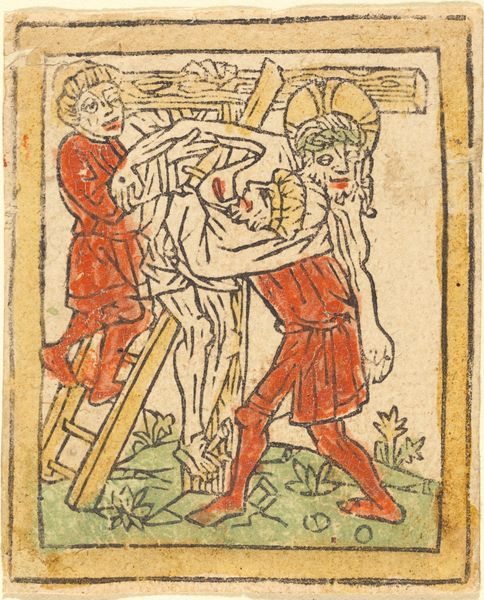

Editor: Here we have "Saint Sebastian," a woodcut made around 1490 by an anonymous artist. The small scale gives it the feel of something almost intimate, despite the violence of the subject. What strikes you when you look at it? Curator: I immediately see the woodcut as evidence of a specific mode of production. Look closely at the labor involved. A block of wood painstakingly carved, then printed, allowing for mass distribution. The very nature of the woodcut – its accessibility – challenges the exclusivity often associated with "high" art. Editor: So you’re less interested in the saint himself, and more in…the process? Curator: Precisely! Consider the economics of it. These prints weren't made for palaces; they were made for everyday devotion, reaching a far wider audience. The material and the process dictate the image’s reception and its role within society. Where was this print sold? What was the social class of people purchasing and viewing it? These are key to interpreting its cultural value. Editor: That’s interesting. I was focusing on the religious symbolism. Curator: The symbolism certainly plays a part, but how does the *making* of the image reinforce or subvert that symbolism? A painted altarpiece communicates something very different. This print emphasizes the materiality of belief. It makes devotion tangible, repeatable, consumable even. It’s about accessibility over awe. Editor: I never thought about it that way before – as almost a devotional object produced through something like industrial means. Thanks! Curator: And it’s through exploring the art's making and distribution, we find its deeper resonance within its historical context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.