Dimensions: height mm, width mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

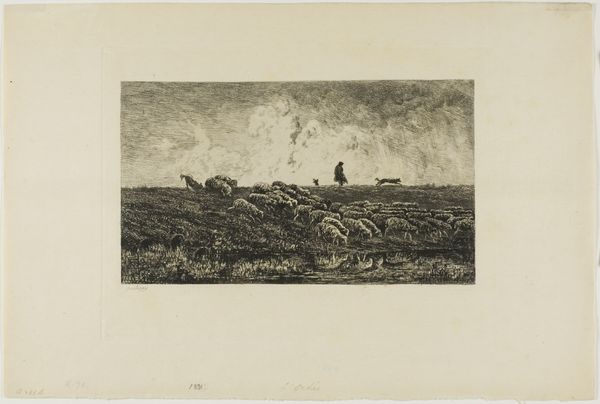

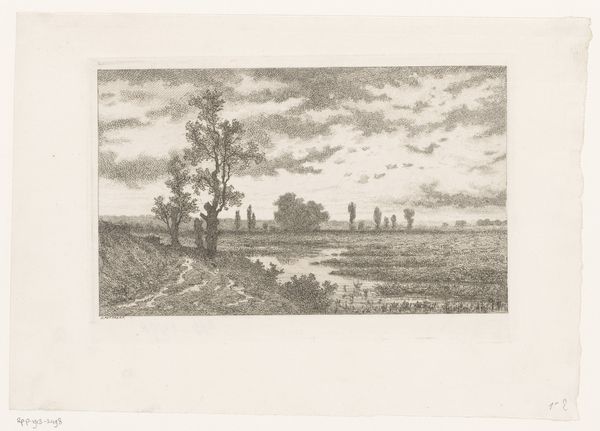

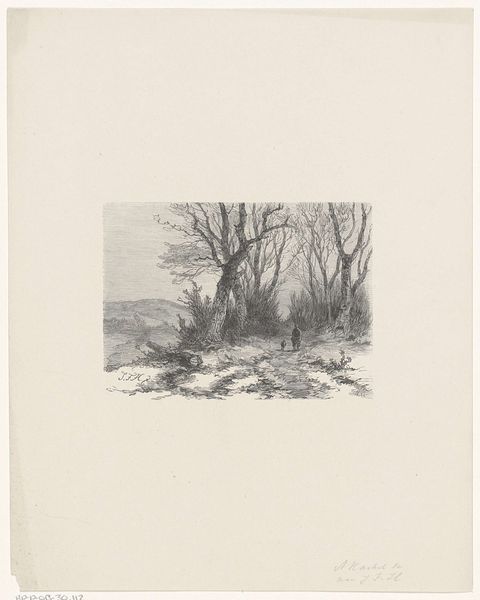

Editor: So this is "Flat Landscape with a Man with a Walking Stick" by Willem Steelink II, likely created between 1866 and 1886. It's a print, an etching. It strikes me as a very solitary scene; the lone figure really dominates the emotional feel. What do you make of it? Curator: Indeed. Solitude is a powerful thread throughout, but let’s think about this solitary figure in context. What symbols might resonate with an audience of the time? What did travel and landscapes evoke for 19th-century viewers? Editor: Perhaps a journey, either literal or metaphorical? Maybe reflecting on the human condition in nature? Curator: Precisely. Consider the walking stick; a common symbol of pilgrimage, self-discovery. The vast landscape itself? A representation of the inner self, inviting introspection. The figure, rendered small against that immensity, underscores our fleeting existence within something eternal. What is the Dutch Golden age context? How do the figures look within their enviroment? Editor: That’s interesting. It moves it away from being a simple scene of rural life into something more profound about humanity's place in the world. So, he is alone. I’d now say he is not simply isolated, but intentionally separating from a crowd. Curator: And this separation from the crowd would give what purpose? It can signal nonconformity, seeking individual understanding and personal liberty. The image creates a space for viewers to think critically and explore how identity can exist independently. Editor: Okay, that connects a lot of dots for me. I initially saw just a man in a field. But now, it’s like the artwork is actually a mirror. The symbol changes by who views it. Curator: Visual symbols act as cultural artifacts that embody shared beliefs and anxieties. When interpreted, we access a reservoir of shared memories. Every element carries potential significance that helps reveal how deeply visual narratives influenced societies, beliefs, and individual psychological states. Editor: I see the picture now is a container of culture! The symbolic part needs to be viewed historically in that society. Curator: It can change again for each generation as they apply personal ideas and experiences. Art history then continues its evolutionary meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.