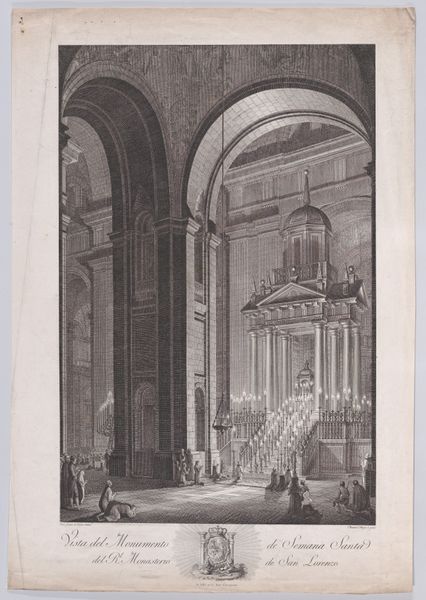

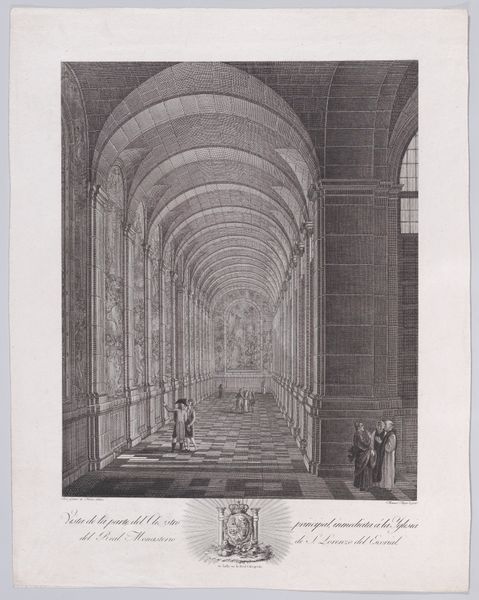

The main staircase of the monastery of El Escorial, from a series of Views of El Escorial 1785 - 1795

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: Sheet: 18 1/2 × 14 9/16 in. (47 × 37 cm) Image: 14 3/16 × 11 1/2 in. (36 × 29.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

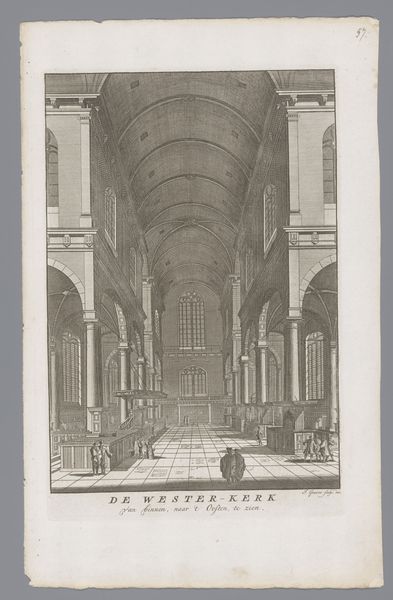

Curator: This print captures "The main staircase of the monastery of El Escorial, from a series of Views of El Escorial," dating between 1785 and 1795. Editor: The immediate feeling is one of grandeur, certainly, but also something strangely cold about this vast architectural space rendered in etching and engraving. It's quite a stark contrast in monochrome. Curator: El Escorial was, and is, meant to impress. Built under Philip II, it functioned simultaneously as a monastery, royal palace, mausoleum and library, all reflecting the power and piety of the Spanish monarchy. Prints like this circulated images of power. Editor: Yes, but let’s think about the sheer labor that went into constructing this. Look at the precision in the etching to depict all that stone and plaster. Who were the artisans, the draftsmen who produced this and the monument itself, and what did they get out of it? It speaks volumes, not just about a royal commission but about a system of production. Curator: Precisely! This print and the series to which it belongs helped construct a vision of Spanish identity. It circulated in a period of nascent Spanish nationalism, reinforcing the links between monarchy, Catholicism, and national pride. These architectural prints become political tools. Editor: Consider too, the materials chosen and the techniques involved; etching and engraving were hardly new by the late 18th century, but their continued use solidified existing artistic hierarchies. They reinforced the "fine art" status of the image versus something quickly sketched or rendered in less time-intensive mediums. Curator: Absolutely. Prints like these served as status symbols, showcasing not just wealth but cultivated taste and participation in a specific visual and political discourse. Their very existence shaped how people saw themselves in relation to power. Editor: It all makes one wonder what stories these very stones could tell us if we actually listened closely enough. Curator: Indeed, beyond its artistic merits, it serves as a document that allows us to unravel layers of social, political and aesthetic intent.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.