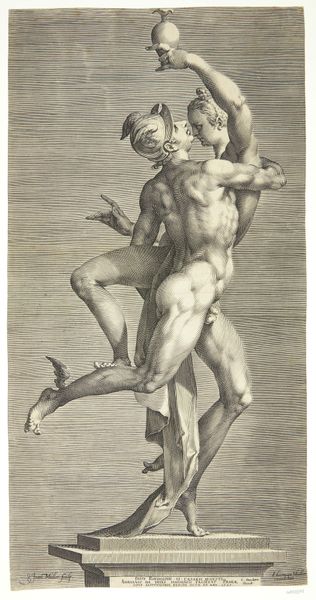

Apollo and Daphne, after Lorenzo Bernini’s Marble Group in the Galleria Borghese, Rome 1736

0:00

0:00

jeanetienneliotard

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 66.2 cm, width 51.2 cm, weight 8.6 kg

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jean-Étienne Liotard’s “Apollo and Daphne, after Lorenzo Bernini’s Marble Group in the Galleria Borghese, Rome,” created in 1736. It's a pastel drawing and rather striking. What intrigues me is the translation from sculpture to drawing - how does Liotard grapple with representing three-dimensional marble in two-dimensional pastel? Curator: Excellent observation. Considering Liotard’s artistic context, what implications arise from reproducing Bernini’s sculpture through drawing using pastel? We can interpret pastel, often associated with preparatory sketches or portraiture in the 18th century, as a medium deeply entangled with artisanal skill and material accessibility. Think about the labour required to produce pastels themselves, the pigments sourced, and their social value in a world of patronage. Editor: So you're saying it's less about a faithful reproduction and more about engaging with the *process* of making and its broader cultural implications? Does the use of pastel also bring the grand, almost industrial scale of marble sculpture down to something domestic and easily consumed? Curator: Precisely. The shift in materiality is significant. Marble represents permanence and wealth, heavily influenced by its extraction, transportation, and the workshops required to manipulate it. Pastel, conversely, is more immediate, fragile, and closely linked to individual artistic skill. Consider this drawing as a commodity – an easily disseminated version of a high-status artwork, available for a different, possibly bourgeois, market. It also begs the question, to what extend does art imitate material production, and how can the inverse take place? Editor: I see it now. So by changing the material, Liotard isn’t just copying a sculpture, but he’s making a statement about art's role in society and who has access to it. Thank you! Curator: Exactly. Analyzing the material and production illuminates the social and economic context. That approach provides insights traditional art history often overlooks.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

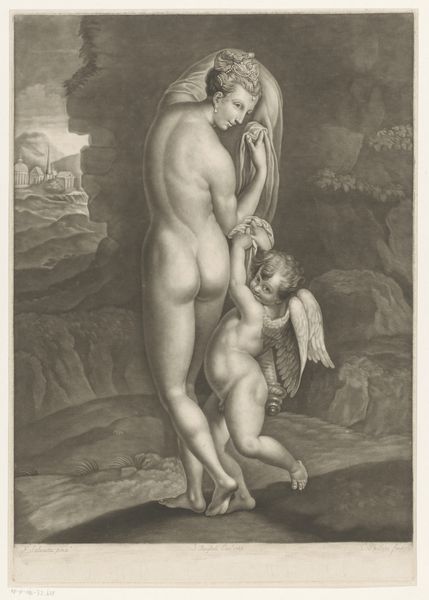

Liotard has here copied another famous marble sculpture. As well as providing a landscape and stormy sky, he has added the river god Peneus, who changed the nymph into a laurel tree to prevent her being ravished by Apollo. Liotard’s attempts to animate marble sculptures are an idiosyncratic contribution to the paragone, the long-running debate as to the relative superiority of painting and sculpture.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.