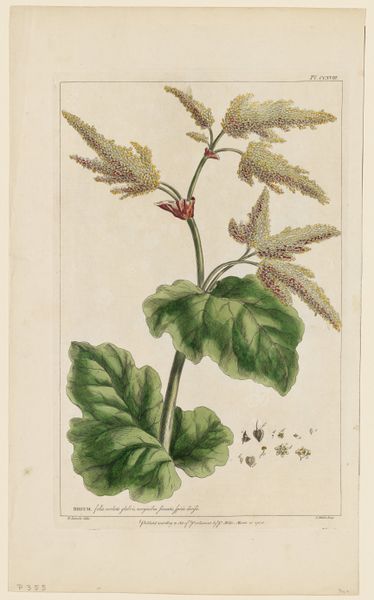

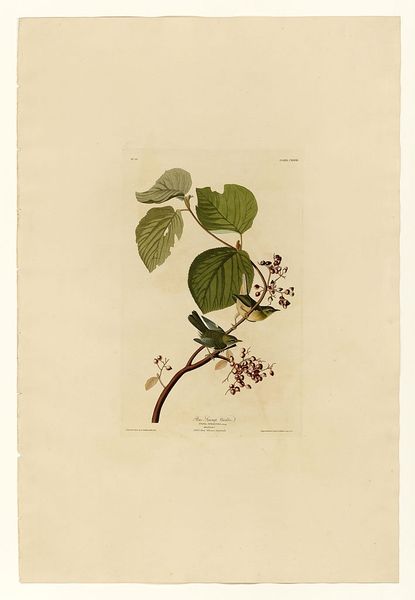

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

engraving

#

botanical art

#

realism

Dimensions: 12 3/4 x 9 7/16 in. (32.39 x 23.97 cm) (plate)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What a serene study. We're looking at a 19th-century drawing and print entitled "Noisetier d'Amerique," attributed to Michel Bouquet and currently held at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. It is done in ink and engraving, perhaps touched with color pencil. Editor: My first impression is how meticulous and understated it is. The rendering is so detailed and subtle—it speaks to a real reverence for the natural world, but something also feels slightly detached, clinical even. It's almost like a botanical specimen under glass. Curator: That's insightful. The hazelnut, or "Noisetier," in the context of iconography, often symbolizes wisdom and, perhaps ironically here, reconciliation. The precision lends it the air of scientific illustration, of cataloging and preserving a very specific truth about the natural world. And that precision becomes meaningful in the context of understanding cultural narratives around nature and knowledge at the time it was produced. Editor: Absolutely. I am also reminded of the complicated histories that haunt botanical illustration in general. Think about colonization and resource extraction, the ways in which such seemingly "objective" images were often implicated in mapping, surveying, and exploiting territories. This print comes across as rather detached, especially from land relationships—it reduces nature to the consumable object. The history here needs to be critically understood in its implications to indigenous exploitation. Curator: And you see that detachment reflected in the piece itself, even? Perhaps in the stark white background, the disembodied sprig hovering in a kind of visual vacuum. Although that background could reference vellum. Editor: Precisely. It strips the hazelnut of its ecological context. This "dissection" flattens the ecological nuances through the objectification, further disconnecting people from the environmental significance the nuts would carry culturally and environmentally. We have a responsibility, as interpreters of these works, to foreground the socio-political power dynamics embedded within the natural world. Curator: An important perspective indeed. Even if unintentionally, art pieces often capture the ethos of their time in profound ways. Focusing on this work has clarified how we might engage with scientific studies through decolonization. Editor: It allows us to look past our first impressions and question the narrative this drawing holds to reconstruct dialogues between nature and colonialism. It also teaches us not to consume art passively.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.