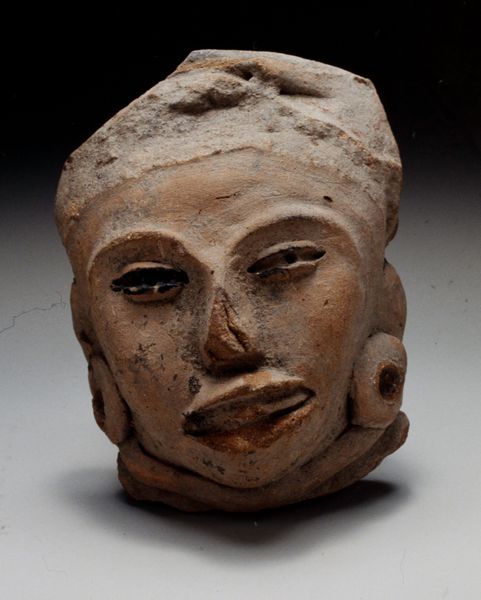

earthenware, sculpture

#

portrait

#

sculpture

#

figuration

#

earthenware

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

Dimensions: 3 1/2 x 2 1/4 x 2 in. (8.9 x 5.7 x 5.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Right, so this is an earthenware sculpture entitled "Head," and its date is unknown. It's currently held at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. I’m struck by how simple and sturdy it seems. What do you see in this piece from a historical perspective? Curator: The sculpture’s anonymity and lack of a precise date are immediately suggestive. This removal from a clear historical mooring forces us to consider it more broadly, as an artifact that speaks to the construction and display of cultural identity. It exists in the public realm divorced from a specific known past. Who decides its significance, and how does that influence our viewing of it? Editor: That's interesting. The very lack of information *becomes* part of the narrative. Does its presence in the Minneapolis Institute of Art give it a different meaning than if it were, say, still at its original site? Curator: Absolutely. Museums are never neutral spaces. Displaying it here elevates it, presents it as something worthy of study and admiration. This, of course, prompts questions about whose cultures are valued and presented in art institutions. Think about how display practices – things like lighting, the height at which it is mounted, and the accompanying label – affect the way we understand it. Editor: So, the way it's presented affects what we think it *is*. Considering it's a “Head” in isolation, how might its presentation shape conversations around the human form? Curator: By presenting a fragment of a larger whole, the museum creates a narrative of incompleteness. Are we meant to imagine the rest of the body? To ponder what is missing? How does this isolation alter our perception of the individual, and perhaps by extension, the broader community they belonged to? The presentation invites speculation, and the museum actively guides the viewer toward certain interpretations through these display decisions. Editor: That really sheds light on the power museums have to shape our understanding. It's far more than just showing us beautiful things; it's constructing a whole story. Curator: Precisely. Recognizing that museums are active agents in constructing historical narratives encourages us to be more critical and conscious viewers.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.