print, ink, color-on-paper

#

ink painting

# print

#

japan

#

handmade artwork painting

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

color-on-paper

#

wedding around the world

#

watercolour bleed

#

watercolour illustration

#

cartoon carciture

#

sketchbook art

#

watercolor

#

multiple paintbruush use

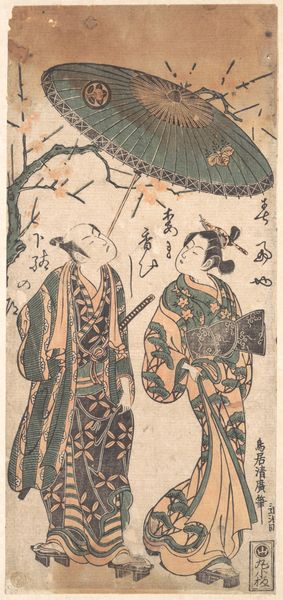

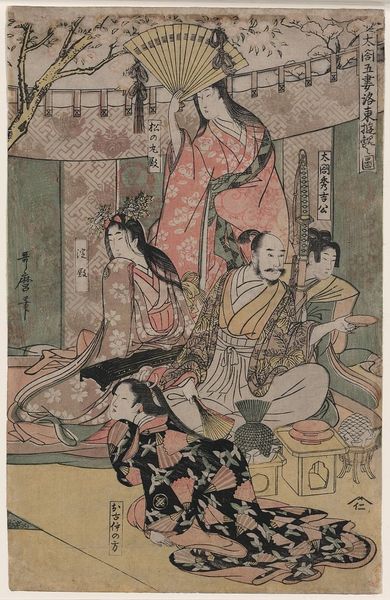

Dimensions: 14 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (36.9 x 24.1 cm) (image, sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: I’m immediately drawn to the sheer layering of this image. The meticulous patterns in the women's robes, the texture of the bamboo stalks... it speaks volumes about the artist's labor. Editor: Indeed. Here we have Eishin's "The Prostitute Hanaōgi of the Ōgiya House," dating circa 1796-1797. It’s currently held at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, a striking example of color-on-paper printmaking from Japan. And to your point about labor, these prints involved an entire system of production, from artist to block cutter to printer, often outside the direct control of the artist. Curator: Exactly. It really undermines the myth of the singular artistic genius. We must remember these Ukiyo-e prints were a highly commercial, mass-produced commodity for urban audiences. Who were these women for? What was the material reality behind their seemingly opulent life? Editor: Certainly. These images, though seemingly celebrating the courtesans of the Yoshiwara district, functioned within a specific social and economic structure. Hanaōgi was not just a name, but a brand cultivated by the Ōgiya House. These prints served as a form of advertising, circulating idealized images tied to that house's prestige and economic power. Curator: I see that interplay between production and consumption at the heart of this work. How the printed image facilitates the consumption of the courtesan’s persona, turning her into an object to be desired and bought, both literally and figuratively. Look at how the elaborate kimono dominates the composition; it becomes the key product on display. Editor: Right, the kimono itself signifies status, skill, and investment. The museum acquiring and displaying a piece like this… It shifts that cycle of commodification, doesn’t it? The art world legitimizes what was once considered a form of popular entertainment and transforms it into high art. Curator: Precisely, that transformation impacts our understanding. We often divorce the object from its production process, missing the web of craft, commerce, and consumption that once gave it meaning. Editor: This piece makes us confront how images participate in shaping social perceptions, class divisions, and gender roles. Curator: Well, that's a compelling glimpse behind the scenes! Editor: Indeed; it provokes thoughts about commerce and the power dynamics that shape the art world, both then and now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.