photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

black and white photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

monochrome

#

monochrome

Dimensions: image/sheet: 24.7 × 24 cm (9 3/4 × 9 7/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

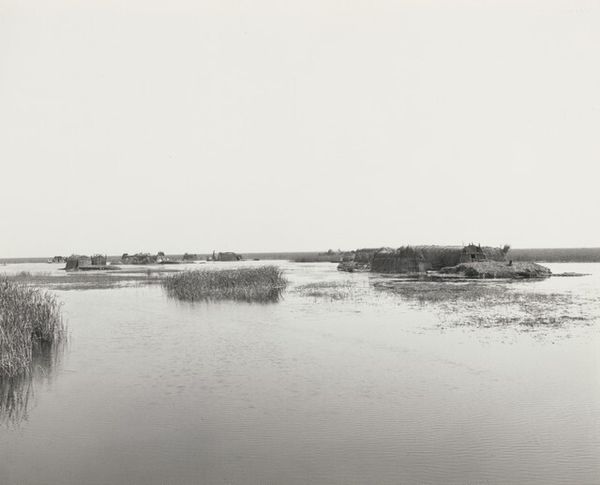

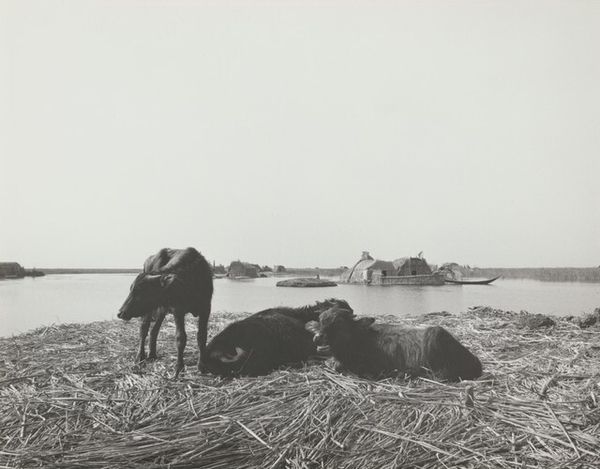

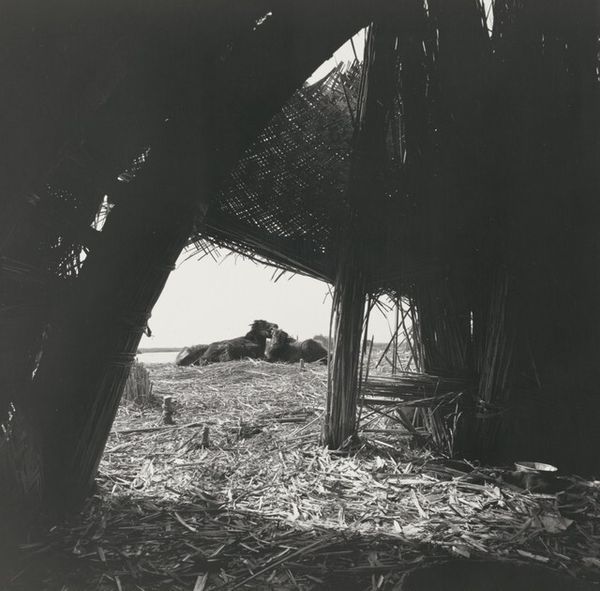

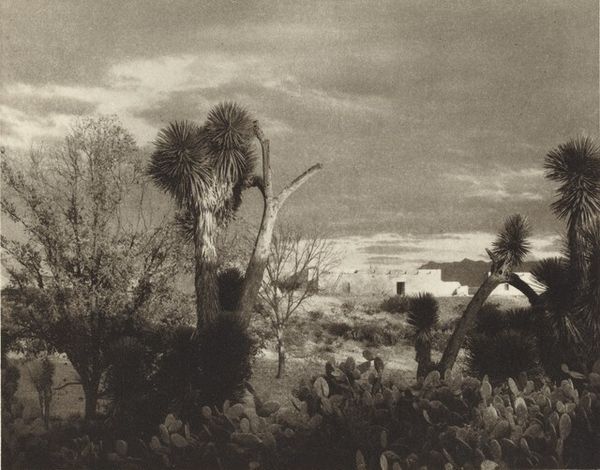

Curator: Ursula Schulz-Dornburg captured this untitled gelatin silver print in 1980. Editor: It’s…dreamlike. Like peering into a lost world through a veil of reeds. I can almost feel the humidity and the buzzing of insects. Is that terrible, or is that photography working its magic? Curator: Not terrible at all! The artist consistently examines how landscape reflects human history and social conditions. Here, the monochrome adds to that ethereal quality you’re feeling, blurring the lines between past and present. Editor: There's a raw beauty to it, isn't there? The fragility of those makeshift dwellings amidst that almost overwhelming natural environment. You can feel how temporary, how conditional that space is. It feels charged with the idea of how a culture clings to exist on an otherwise blank or even unhospitable horizon. Curator: Absolutely. Schulz-Dornburg often focuses on landscapes marked by transition, erasure, and the resilience of the communities that inhabit them. I think of indigenous architectures and settlements and how landscape changes but still holds on to their shapes. Editor: It also really drives home the role of photography as cultural evidence. I mean, someone looked at that and thought, "this needs to be seen, needs to be remembered." Even in its ambiguity, or maybe precisely because of it. It begs the questions. What's the significance of these constructions? Who are these individuals caught between nature and these handmade refuges? What choices or pressures or historical circumstance resulted in what's unfolding? It's less of an image, I think, than a meditation on ephemerality, human will, and documentation. Curator: Very true. What it might have been like living and inhabiting it. As for me, seeing those dwellings now, decades later, and still trying to understand. How do we even begin to grasp the context, what has become of it, and ultimately its significance? Editor: I keep coming back to those blurred figures, as if the artist is not pointing out where, or who they are, but almost an existential question of, what am *I*, humanity, doing *there*? Curator: I’m struck with a renewed awareness of humanity and architecture. Schulz-Dornburg is always an emotional catalyst.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.