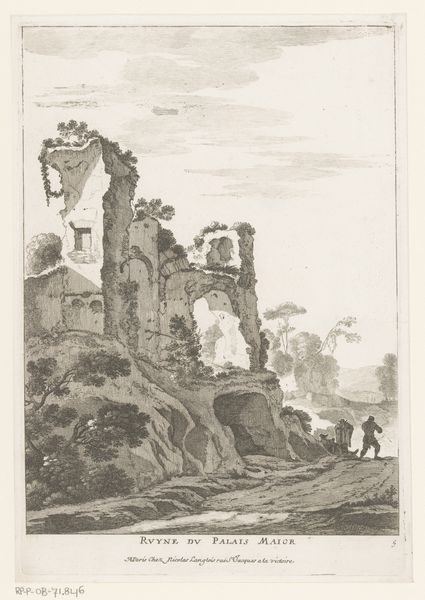

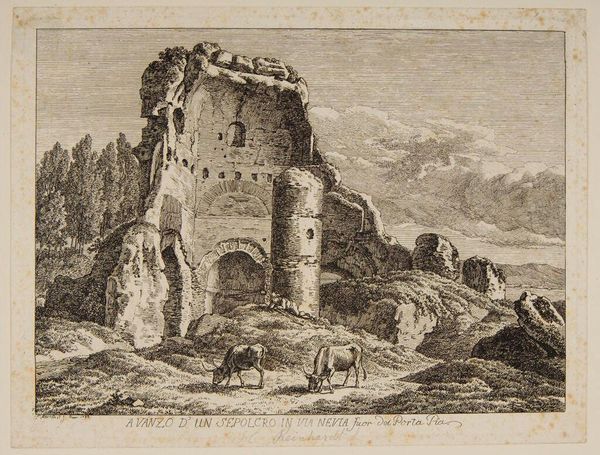

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 236 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Leonardus Schweickhardt's "Rocky Landscape with Houses," likely created sometime between 1793 and 1862. It's an engraving, a print. I'm immediately drawn to the contrast between the imposing rock formations and the delicate details of the cityscape. What do you see in this piece? Curator: It's fascinating to view this engraving through the lens of 19th-century Romanticism and its focus on ruins. Notice how Schweickhardt isn't just depicting a landscape, but actively framing a meditation on time, as clearly evidenced in the French text etched below, hinting at both destruction and creation. Where would this type of imagery be consumed? Who was viewing and buying? Editor: Good question. Presumably, prints like this were more widely available than paintings. Perhaps a burgeoning middle class interested in art but without access to wealthy collections? The style definitely caters to Romantic sensibilities, right? The dramatic landscape, the implication of human insignificance… Curator: Exactly. And think about the sociopolitical context! These images, often distributed as prints, offered viewers a picturesque escape but also subtly reinforced ideas about history, nature, and national identity. Were they just consumers, or were these prints contributing to social changes, even nationalistic fervor? Consider its availability, its cost to access the imagery, and the location where art like this was consumed and enjoyed. Editor: It makes me think about the power of imagery in shaping public opinion, even through something as seemingly innocent as a landscape print. I never thought about art consumption that way. Curator: That's the crux of it! By examining these pieces within their historical moment, we start to unravel the complex ways art was interwoven with social, cultural, and political currents. The history is etched right into these prints. Editor: This has completely changed how I look at landscapes! Now I see stories within them, dialogues with the past, with complex political issues that I had never stopped to examine before.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.