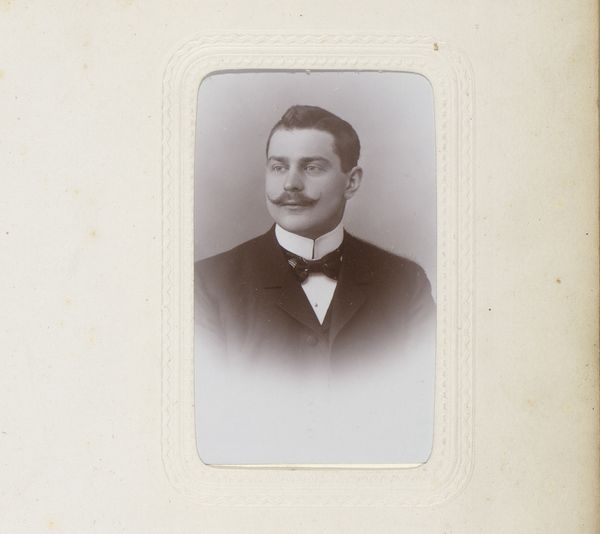

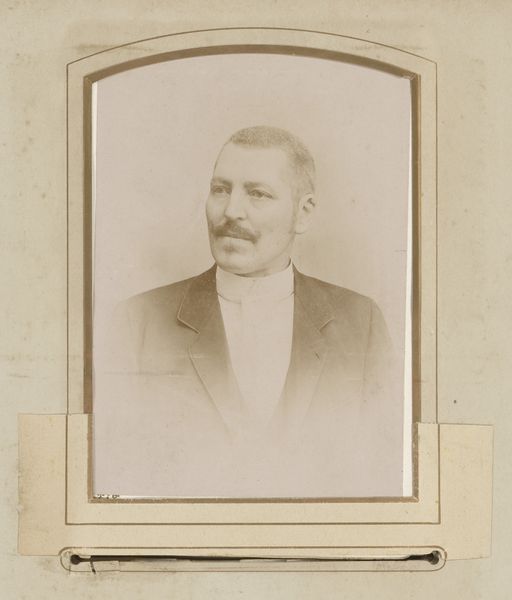

daguerreotype, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

self-portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical fashion

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

paper medium

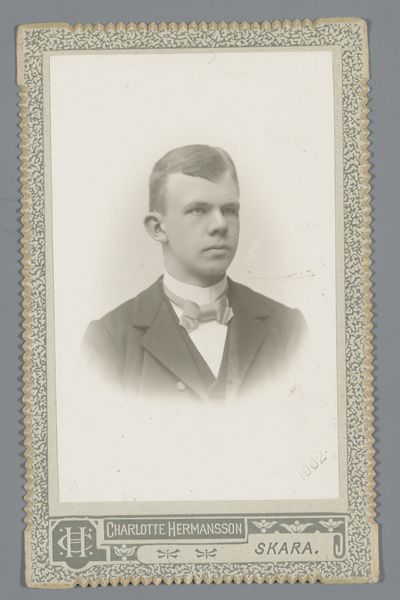

Dimensions: height 99 mm, width 59 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

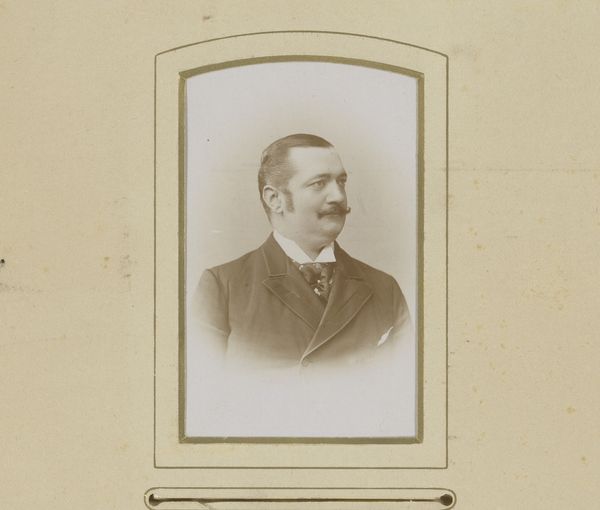

Editor: This is a gelatin silver print, *Portret van een onbekende man*, by Théodore Gedoelst, dating from around 1866 to 1883. The gentleman’s formal attire, like his carefully groomed mustache, suggest a certain social standing, yet there is a haunting vulnerability in his eyes. How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see more than just a portrait, I see a glimpse into the complex social landscape of the late 19th century. The formal attire does speak of class, but let’s also consider the emerging technologies of photography and how they democratized portraiture, making it accessible to a wider segment of the population. Does this man embrace the burgeoning Industrial Revolution, or is he clinging to a bygone era? And whose gaze are we really meeting here, the man’s or the photographer’s? What are the power dynamics in play between the photographer, the subject, and ultimately, the viewer? Editor: That’s fascinating! I hadn’t considered the power dynamic involved in the act of photographing someone. So, by viewing this photograph, are we engaging in a kind of observation that wasn't necessarily intended? Curator: Precisely! Think about it: photography initially served as a tool for documentation, scientific progress, even surveillance. Portraits, especially of unknown subjects, can unwittingly reveal societal norms, biases, or power struggles of the time. Does his somewhat stiff posture reveal more about gender norms? His social position? Do his clothes define him or imprison him? Editor: That makes me look at the portrait completely differently. It’s not just a picture of a man; it’s a historical artifact, filled with all sorts of cultural information. Curator: Exactly. Art constantly challenges us to unpack historical narratives, question ingrained assumptions, and consider whose stories are told and, more importantly, whose remain hidden. Editor: Thank you. I definitely learned a lot and it gave me a completely different way of seeing photographic portraiture from this period.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.