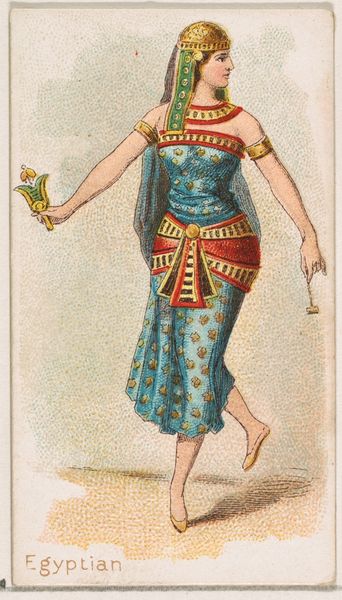

Bengalese Dancer, from the Dancing Women series (N186) issued by Wm. S. Kimball & Co. 1889

0:00

0:00

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

coloured pencil

#

orientalism

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 11/16 × 1 7/16 in. (6.9 × 3.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This work is titled "Bengalese Dancer, from the Dancing Women series," issued in 1889 by Wm. S. Kimball & Co. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the lithographic texture—how it gives a kind of shimmering quality to the dancer’s garments, almost as if light is radiating directly from the cloth itself. Curator: It’s fascinating to consider this print in the context of late 19th-century Orientalism and Japonisme. It clearly caters to a Western audience’s fascination with—and often misrepresentation of—Asian cultures, particularly through the lens of exoticism and feminine allure. Editor: Right, the means of production is crucial here; a commercial firm creating images intended for mass consumption. This challenges our conventional view of art. I am curious how it was printed? The way the artist layered colour pencils on paper—was it printed using lithography, which then lends itself well to mass reproduction? How did that affect the material value? Curator: The "Dancing Women series" functioned, in a way, as cultural ambassadors—however flawed their message might have been. The print presents an idea of Bengali culture and womanhood—but of course, that portrayal lacks the complexity of lived experiences. What does this kind of cultural fantasizing serve to the West? Editor: It served to stimulate desire through images, creating fantasies of the “Orient” and a commercial need to produce the work on a massive scale! Curator: It prompts questions about the female body, particularly when it’s framed by a Western gaze that dictates how these bodies should be seen, consumed, and understood. Is it exploitative, or is there also some sense of empowerment—however limited—for the woman being represented, given her implied movement, agency, and dynamism? Editor: Interesting points, yet, isn’t this also an example of the colonial exploitation of image-making itself? These trade cards, distributed in packets of tobacco, literally commodified another culture in the name of profit. Curator: Precisely, but what resonates today is the sheer audacity of conflating culture, representation, and capitalist consumerism, then and now! Editor: Yes. This print shows that the so-called high or fine arts have always depended on the production and labor of commercialized art practices to build upon new processes and technology to create art that is now hanging on museum walls.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.