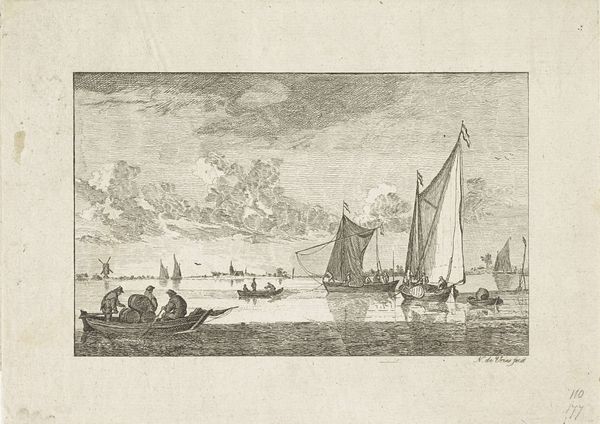

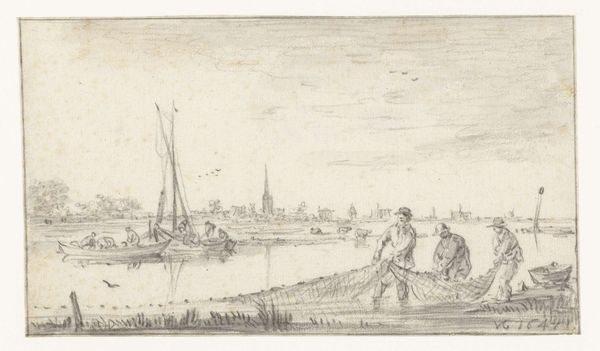

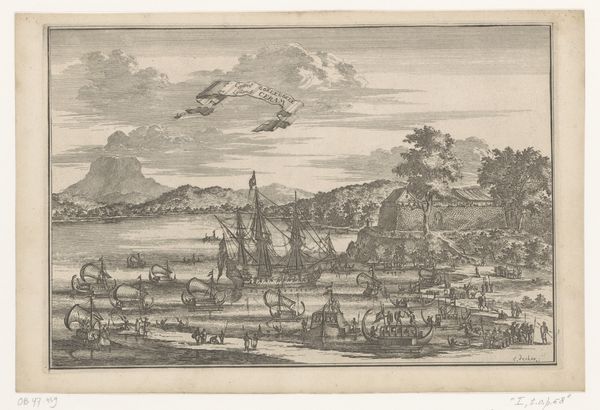

drawing, print, etching, woodcut, engraving

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

woodcut

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 5 3/8 × 8 5/16 in. (13.6 × 21.1 cm) The address has been cut off at bottom right but the removal of the date indicates the Galle printing

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Wenceslaus Hollar’s “The Three Windmills,” completed in 1651, is a striking example of Dutch Golden Age landscape printmaking, currently residing here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Its composition feels both intimate and expansive. Editor: My immediate sense is one of industrious calm. The subtle tonal variations achieved through etching lend it a sort of soft realism, despite its clear artifice. It invites speculation about the depicted societal structures, reflecting Dutch maritime and economic activity. Curator: Indeed. Note the artist’s remarkable control of line, especially in the varied textures. Observe the stippling technique Hollar employed to describe form—the meticulous details capturing light as it dapples on water, brick, and wood. How do you think the symbolism plays here? Editor: I consider the windmills not just as elements of the landscape, but as cogs of Dutch colonial endeavors. It evokes a narrative of class distinctions and maritime dominance during the Dutch Golden Age, the very age referenced within the piece itself. The landscape serves to represent power dynamics inherent at that point in time. Curator: Hmmm, an interesting reading. To look more closely, consider how Hollar situates them against the vast sky, creating depth and emphasizing their architectural form. The organization of the image around those central windmills creates a formal harmony. Editor: However, reducing these windmills to merely an appreciation of form strips away their symbolic connection to global trade. What about their socio-economic function, which provided both subsistence and the apparatus for the burgeoning slave trade? The artist can’t remove that history, regardless of their artistic intent. Curator: It appears, then, that even within a relatively modest sized etching, we locate ample evidence of the dynamism of the period in Dutch society and art history. Editor: Exactly, and in thinking about this landscape today, we reflect on a much more complex sense of spatial and environmental history that lingers even within the careful rendering.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.