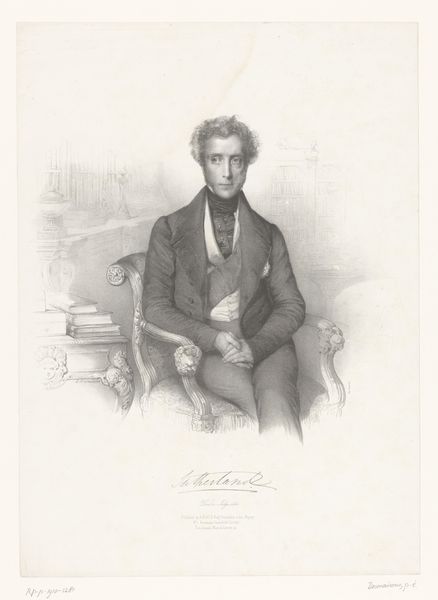

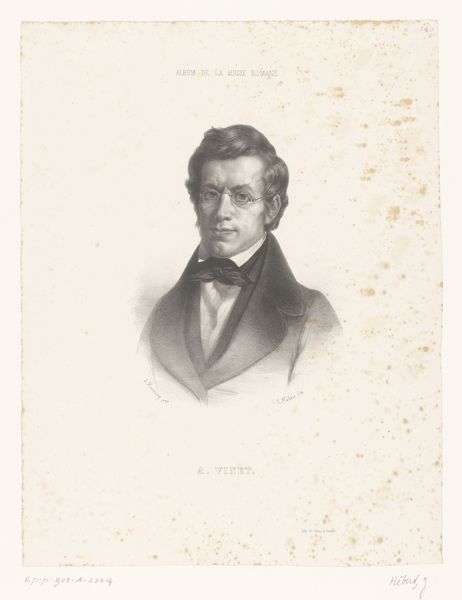

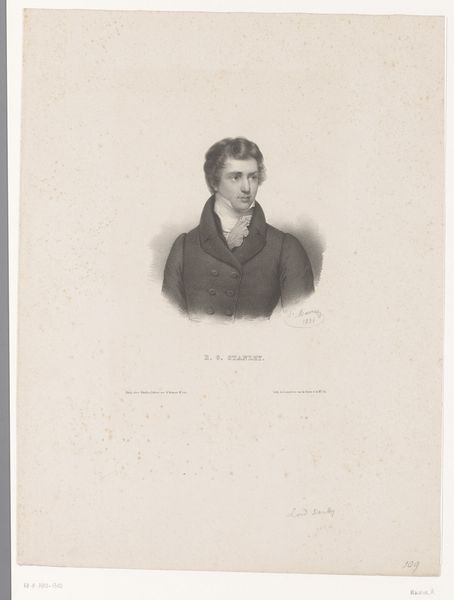

drawing, print, paper, graphite, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

graphite

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 180 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a print, dating from 1825 to 1842, titled "Portret van Jean-Baptiste Sylvère Gaye de Martignac" by Nicolas Maurin. It employs graphite and engraving on paper, a somewhat understated combination. Editor: My immediate thought is...constrained. The tightly buttoned coat, the restrained shading, even the carefully penned signature—it all speaks of a man defined by social expectation. Curator: Indeed. Maurin's use of engraving allows for incredibly fine lines, look at the details on the face. It speaks to a laborious process. Engraving demands a level of technical skill, almost industrial in its precision. We're not talking about spontaneous brushstrokes; this is controlled reproduction. Editor: Absolutely, but what's being reproduced? Martignac was a prominent figure during the Restoration. Knowing that situates this portrait as a document of power. The Romantic era often grappled with representing authority, so, how does this image subtly critique, or perhaps reinforce, the social hierarchy of the time? Curator: Well, look at the subtle gradations in tone achieved through the graphite. It's about presenting an image of authority through carefully crafted material means. The value wasn't in painterly expression but in the artisan's capacity to replicate a likeness accurately and elegantly using what, after all, is a printing technique meant for mass production. Editor: That "mass production" is interesting. Portraits were often commissioned and signified privilege, so even if reproduced in multiples, the availability to a wider audience perhaps democratized, in some measure, access to the representation of power. Was Maurin consciously exploring the implications of accessible imagery during a time of immense social and political change? Curator: It highlights a fascinating tension between the handmade and mass production inherent in printmaking. This wasn't some lone genius pouring their soul onto a canvas. It's a skilled craftsperson manipulating materials to produce a product reflecting its time and Nicolas Maurin created multiples that reflected a wide distribution network and an expanding market for such images. Editor: This image of Martignac makes us ponder ideas surrounding labor, class, access, and visual rhetoric and perhaps suggests that power in this period depended less on physical might and more on curated, disseminated visuality. It causes us to ask: how can artistic representation create a legacy and perpetuate ideologies through very particular material choices and historical narratives? Curator: And what is conveyed depends on how we look, what our priorities are as we interpret that legacy based on method and manner of production. Editor: Exactly. It prompts an essential, enduring dialog.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.