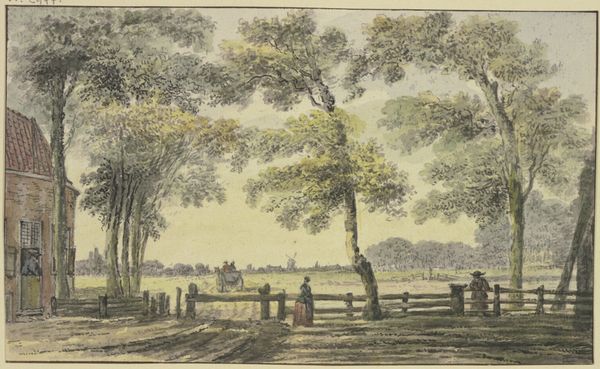

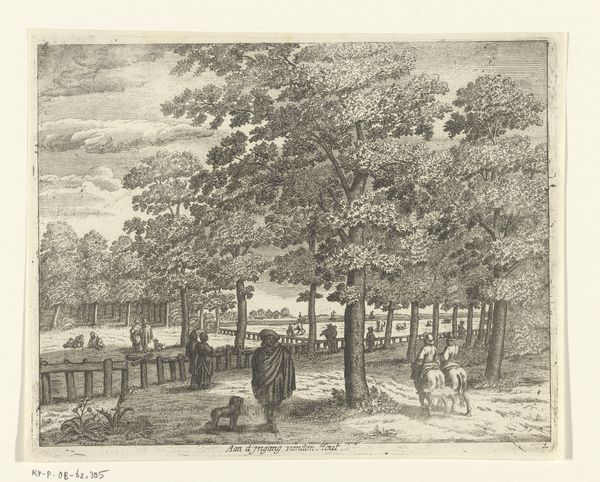

painting, plein-air, watercolor

#

painting

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

rococo

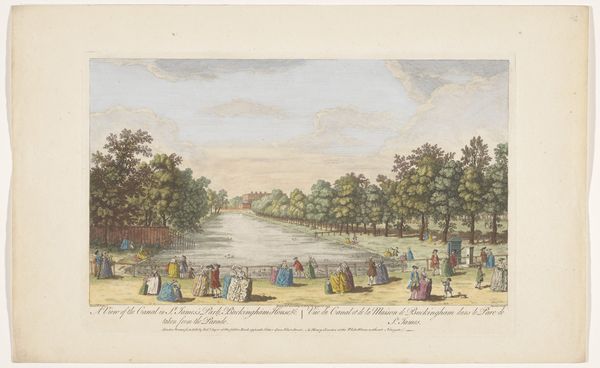

Dimensions: height 262 mm, width 413 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Robert Sayer’s 1752 watercolor and coloured pencil work, "View of Rosamond’s Pond in St. James’s Park, London," offers a fascinating glimpse into 18th-century leisure. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: A genteel stillness. The carefully placed figures almost seem posed against the backdrop of what appears to be manicured nature, giving an idealized view of reality for this era. Curator: The composition certainly speaks to that. Notice the deliberate layering – the eye is led from the figures in the foreground, across the pond, to the meticulously arranged trees in the distance. It’s a masterful manipulation of perspective to create a sense of depth and harmony. Editor: Precisely. But what about the realities outside this frame? St. James’s Park wasn’t just a pleasure garden, it was also a site of social stratification and control. The clothing of the figures speaks to the period and social classes; this was a world defined by status and privilege and access to these places, with gender constraints and limited mobility. Curator: While your point on the socio-economic backdrop is valid, consider the aesthetic choices Sayer made. The Rococo style, with its emphasis on elegance, pastel hues, and intricate detail, is quite present. The use of watercolor lends itself well to these light and delicate tones. Editor: Indeed, the Rococo influence softens the realities, presenting a sanitised version of London life. The park serves as a stage for carefully constructed social performances. This image captures not necessarily what was, but what the elite wanted to see – and to project. What is absent is as telling as what is present in this idyllic scene. Curator: Perhaps so. But focusing on its formal qualities allows us to understand the enduring appeal of landscape art. The carefully balanced composition, the subtle gradations of color, and the overall sense of order create a self-contained aesthetic experience, regardless of its historical context. Editor: True, but the historical context allows us to decode the work and challenge assumptions. It makes us reconsider our relationship with public spaces and our role in preserving and redefining them, perhaps offering to envision beyond the gilded cages of history. Curator: A fascinating divergence; perhaps our viewers will choose which framework resonates most strongly with them. Editor: Indeed. Let’s hope they question, contextualize, and above all, continue to find new ways to see.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.