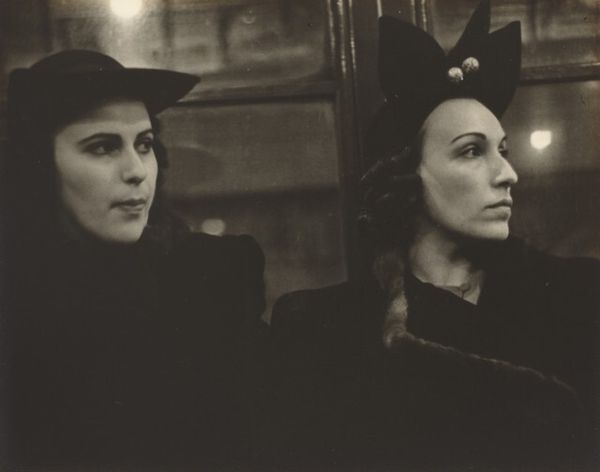

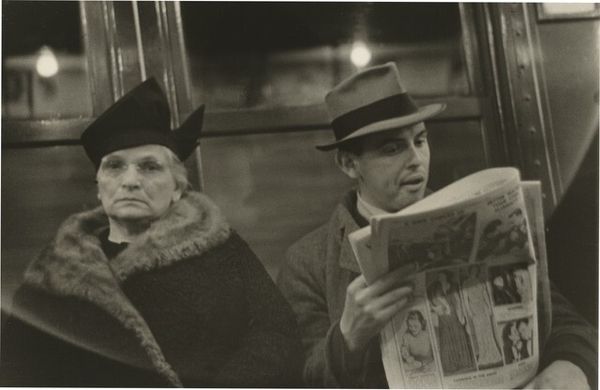

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

black and white photography

#

black and white format

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

modernism

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: sheet: 12.6 x 20.2 cm (4 15/16 x 7 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: This is Walker Evans' "Subway Portrait," taken between 1938 and 1941, using a gelatin-silver print. It's striking how intimate this seemingly candid shot feels, almost as though we're intruding on a private moment within the bustling city. What's your perspective on this work, and how it speaks to its time? Curator: Evans’ work, especially this series, offers a powerful insight into the social fabric of Depression-era America. By using a hidden camera, he bypasses the performative aspect of portraiture. We're seeing, arguably, more 'honest' depictions, although that honesty is itself mediated by Evans’ selection and framing. Do you notice how the anonymity afforded by the subway allows these people to become, in a way, representatives of their class and era? Editor: That’s a great point. They do seem like archetypes in a way. But doesn't the surreptitious nature of the photography raise ethical questions about representation and exploitation? Curator: Absolutely. It forces us to confront the ethics of documentary photography. Evans was working within a context where the idea of objective truth in photography was prevalent, influenced by projects like the Farm Security Administration. But, as viewers, we need to critically consider whether the "truth" captured justifies the lack of consent and the power dynamics inherent in observing these individuals without their knowledge. Editor: So, the value of the image is not just in the aesthetic or technical achievement, but also in the questions it raises about the social role of the artist? Curator: Precisely. The image exists in a historical and ethical landscape that shapes its meaning. The politics of imagery, in this case, pushes us to examine not only what is depicted, but how and why it was depicted in that way. Editor: This really makes me rethink my initial assumptions about documentary photography. Curator: That’s the power of art, isn't it? To make us question the world around us and our place in it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.