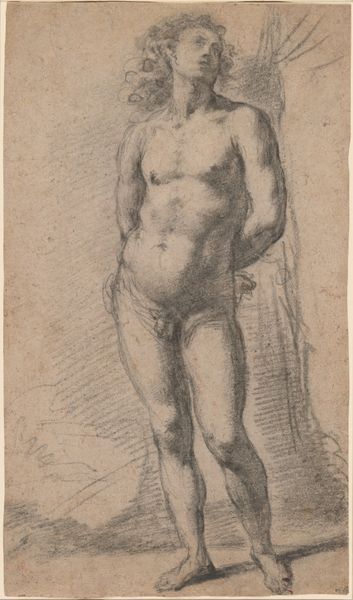

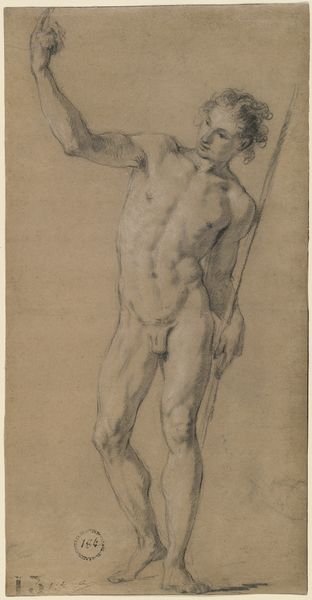

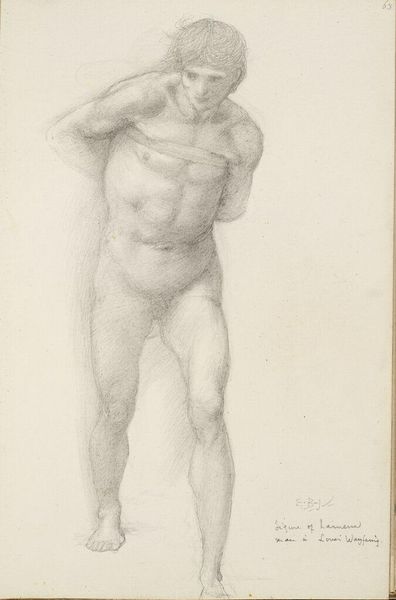

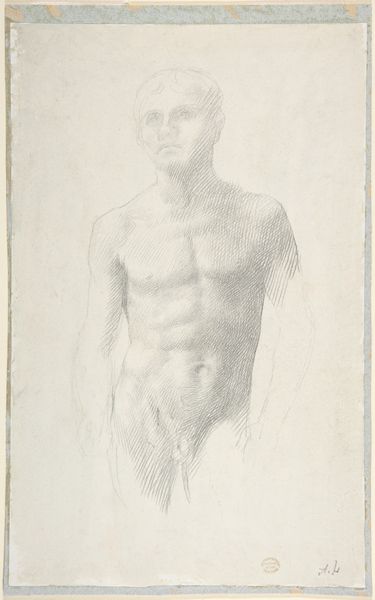

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

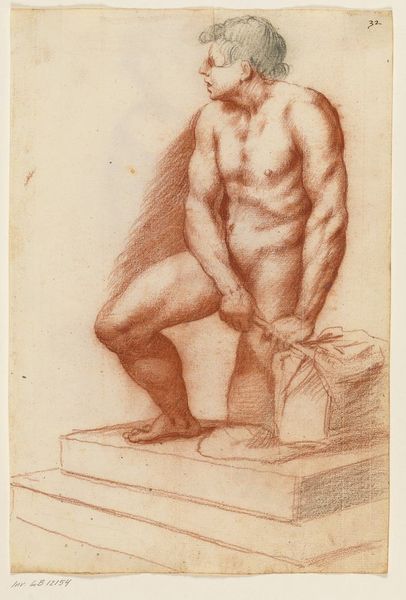

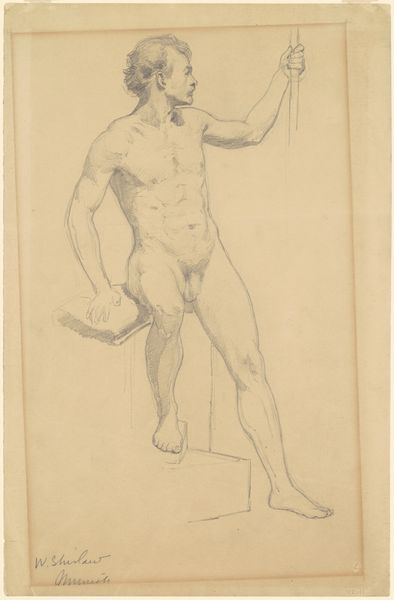

drawing

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

nude

Dimensions: 259 mm (height) x 137 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: So, here we have Willem Panneels' "Front view of a male figure", a pencil drawing dating from around 1626 to 1629, now residing here at the SMK, Statens Museum for Kunst. What are your initial thoughts on it? Editor: My first thought? He looks like he's bracing himself for something. Like he’s heard some bad news and he's thinking, "Oh god, not again." There’s something weary and weighted in the lines of the face. Curator: Interesting, because the drawing actually appears to be a study, probably for a history painting. Considering the time period, we can contextualize these kinds of figure studies as preliminary explorations for larger narratives often depicting biblical, mythological, or historical scenes that carry allegorical weight. The male nude becomes a powerful symbol. Editor: I can see the symbolic potential, for sure. All that Renaissance baggage! But genuinely, he just seems fed up. The slightly hunched posture, the vague, undefined face—there’s a palpable vulnerability there, especially given the... heroic build. I'd never be able to draw muscles like that, honestly! Curator: Precisely! That contrast is critical. Consider the artist’s biography. Panneels worked under Rubens. So we're encountering a study influenced by that Baroque intensity, where even the initial sketch seeks to embody this tension between idealized strength and very human emotional expression. We might look at it, through a post-colonial lens for instance, interrogating this inherent power dynamic. Editor: Oh, totally. The male gaze of it all. But putting my cynical hat aside for a sec... the skill is undeniable. The shading gives such weight to his limbs. It's both idealized and oddly…present. Did he use a live model? Curator: It is presumed to be, though definitive records are scant. If he did, understanding that dynamic is essential; looking at questions of class, access, the objectification inherent within the artist/model relationship in 17th-century European society. Editor: Right, makes total sense. Despite all that… there is something that pulls me in. Makes me feel something of that shared vulnerability you can sense in it today. What do you think? Curator: Ultimately, Panneels’ drawing invites us to reflect on our own relationship with representations of the body and masculinity, inviting empathy across centuries. Editor: Yeah, from powdered wigs to TikTok dances, some things just don't change all that much, huh?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.