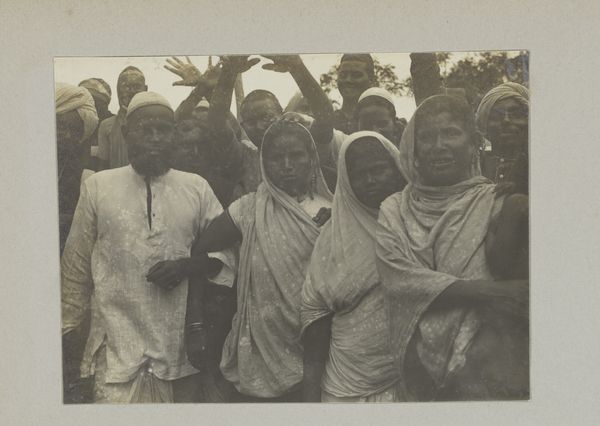

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

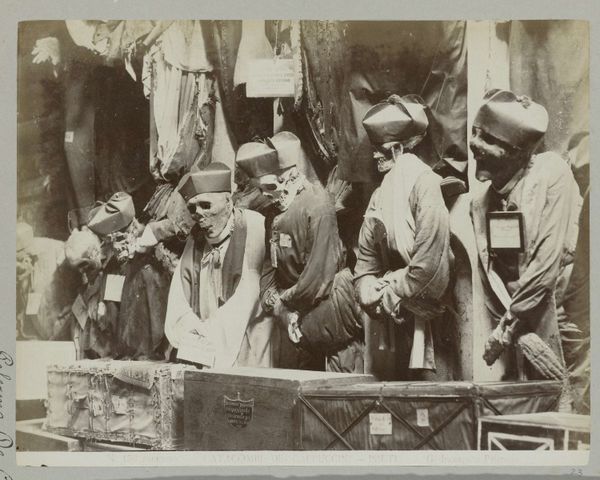

african-art

#

photography

#

group-portraits

#

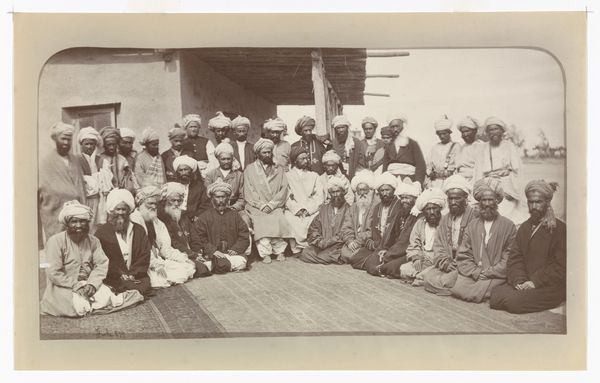

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 78 mm, width 112 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

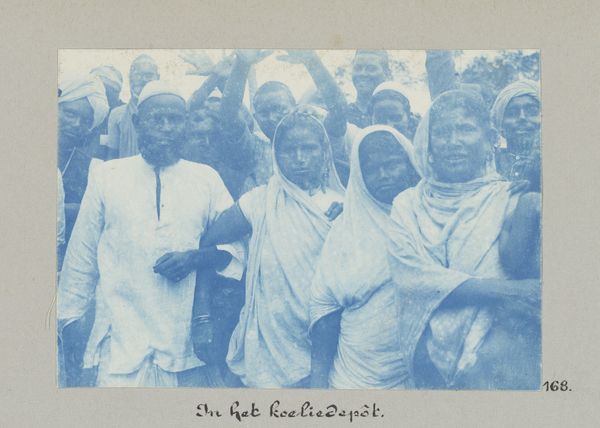

Curator: This is a photograph by Hendrik Doijer, taken between 1903 and 1910, titled "Hindostaanse contractarbeiders in het immigrantendepot," and rendered as a gelatin silver print. It portrays a group of indentured laborers in what appears to be a holding area. Editor: My immediate reaction is one of subdued melancholy. The sepia tones lend it an air of antiquity, but it's the collective gaze of the subjects—or rather, the avoidance of it—that truly strikes me. It’s a powerful, albeit subtle, representation of displacement and perhaps, even resignation. Curator: That downcast gaze you noticed speaks volumes. There’s a palpable sense of detachment. The visual weight of their traditional garments, contrasting against the stark, impersonal backdrop of what I read as an immigrant depot, heightens that feeling of alienation and cultural displacement. Their clothes act as visible signs of origin amid the disorientation. Editor: Absolutely. The photo becomes a visual document of the indentured servitude system. I see the layered complexities of colonial power structures at play. It forces a dialogue around exploitation, labor, and the ways in which identities were reshaped by these historical forces. What visual cues point you to a story of indenture? Curator: A close inspection of their clothing reveals much. Note the variations in dress and adornment. They serve as echoes of specific regions within India, speaking to diverse origins brought together under the singular experience of forced migration for labor. It almost seems as though, here in this transit place, cultural markers still retain symbolic value. Editor: Yes, it makes me consider how people reconstruct community and shared culture under oppressive conditions, or while being stripped of existing identities, even. It's a portrait of a group suspended in a state of liminality—between worlds, between identities. And also how documentary photography itself can carry cultural biases. Whose eye captured this image, and what agenda might it have served? Curator: It is difficult to overlook the nuances of power imbued in the act of image-making. How might their story be visually retold today, acknowledging historical dehumanization and cultural resilience? Editor: Well, hopefully, this photograph is an archive that lets the present look back, confront, and work towards disrupting any continuous manifestations of the past. It offers more than a somber look; it should fuel questions about justice, historical responsibility, and solidarity with all communities touched by the violence of exploitation. Curator: An important image for all its emotional, social, and artistic value.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.