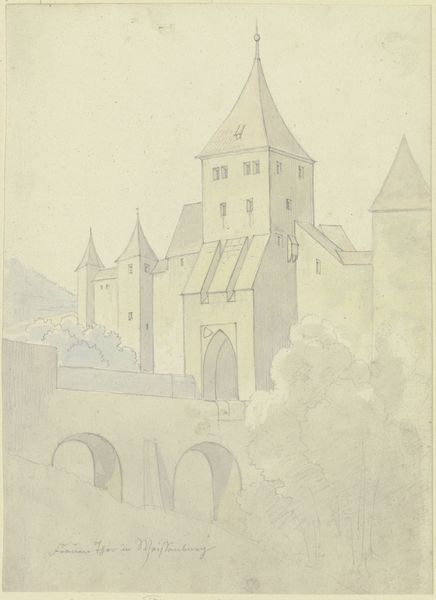

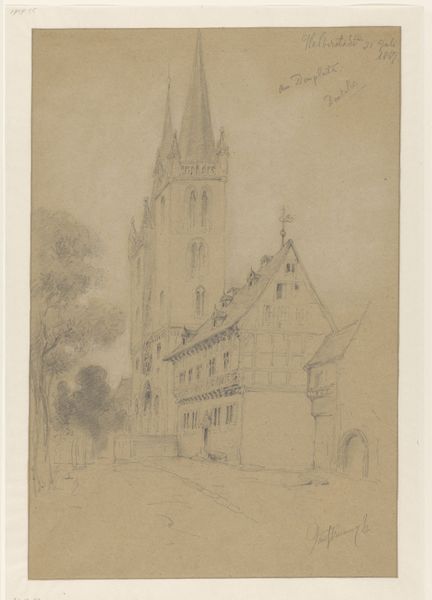

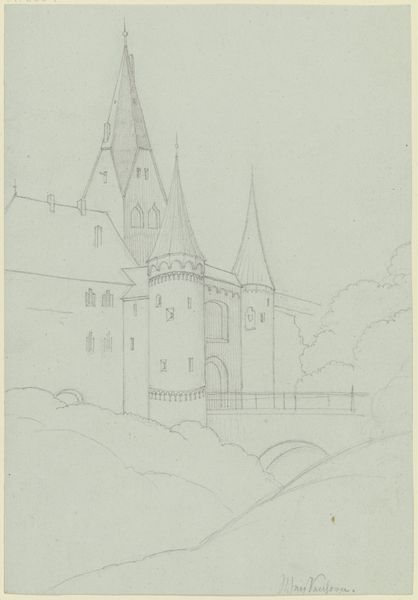

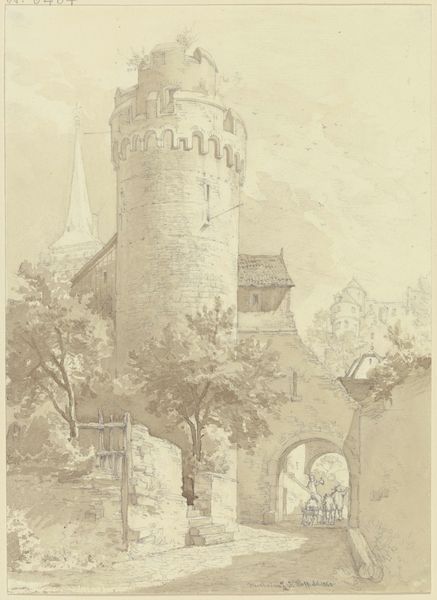

drawing, painting, paper, watercolor, architecture

#

drawing

#

painting

#

landscape

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

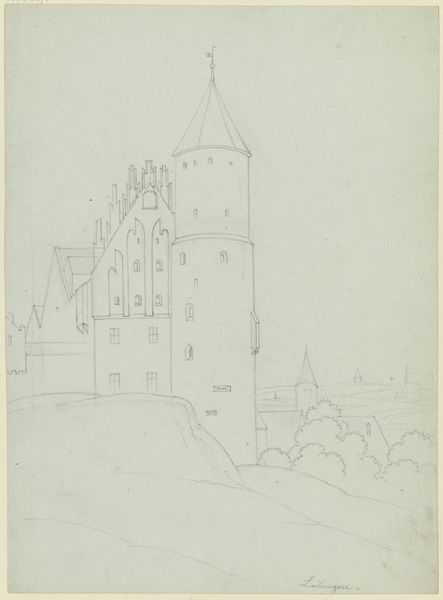

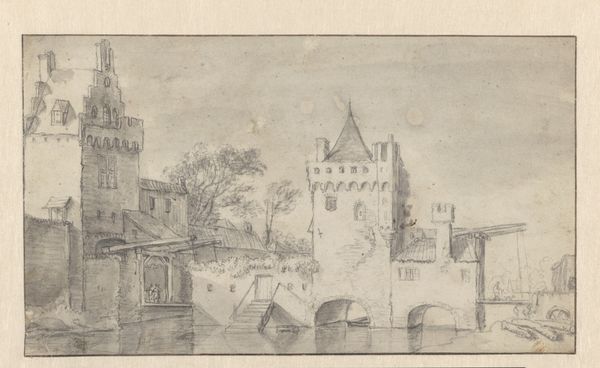

Curator: Before us, we have Karl Peter Burnitz’s "Segovia," dating back to 1850, a work rendered in watercolor on paper. Editor: There’s a sense of faded grandeur here, like looking at a memory through mist. The muted palette lends an almost ghostly quality to the architecture. Curator: The artist employs watercolor to capture not just the physical likeness of the Segovia Alcázar, but also to evoke a specific emotional response—one rooted in the Romantic tradition's fascination with history. How does the structure itself speak to you? Editor: The towering structure clearly dominates the composition. It makes me wonder, what did a medieval castle signify in 1850? What continuities of power were Burnitz and his audience grappling with? We should also remember that watercolor has long held associations with femininity, travel, documentation, domesticity, etc. What significance could these have for this scene? Curator: A fruitful question. By 1850, the castle as an idea was imbued with associations of nationalism and chivalry and was considered very masculine; Burnitz would have known this. Here he has painted Segovia with very ‘feminine’ watercolors, and this combination creates interesting dissonance. Perhaps he is highlighting the ways the medieval ideal failed the modern world, and he communicates that through art? Editor: I hadn't considered Burnitz's watercolor medium as playing with the established view on masculinity. Now, do you think there might be social critiques embedded here? Curator: It’s very possible. Burnitz could have certainly been playing with these very gendered elements. Landscape painting often engages with contemporary societal and political concerns. So viewing Burnitz through a more political and social lens definitely could prove productive. Editor: Exactly. These historical landmarks aren't simply beautiful vistas; they carry cultural baggage. To what extent is Burnitz commenting on the burden of this history? Or just ignoring this subject and painting what he likes the way he likes it? Curator: This reading gives us some intriguing directions for our understanding of the artwork. It opens dialogue beyond just its aesthetic qualities, pushing us to think about the ideologies shaping art in 1850s. Editor: And to see beyond the picturesque. To contemplate the past's influence. I appreciate this artwork even more now, recognizing it is both delicate and formidable, like Segovia itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.