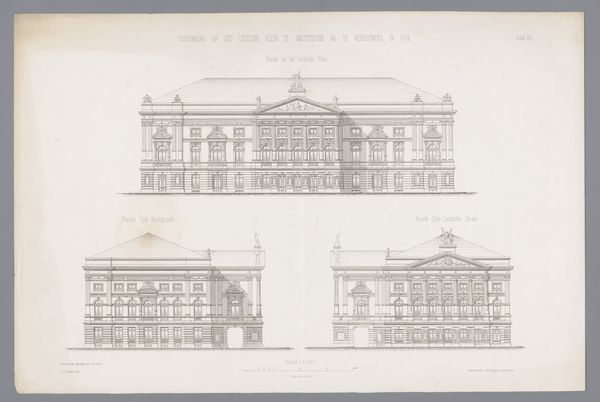

Dimensions: height 458 mm, width 594 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

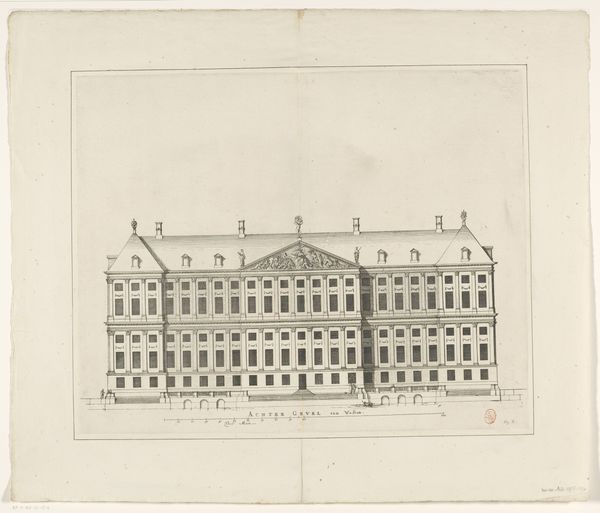

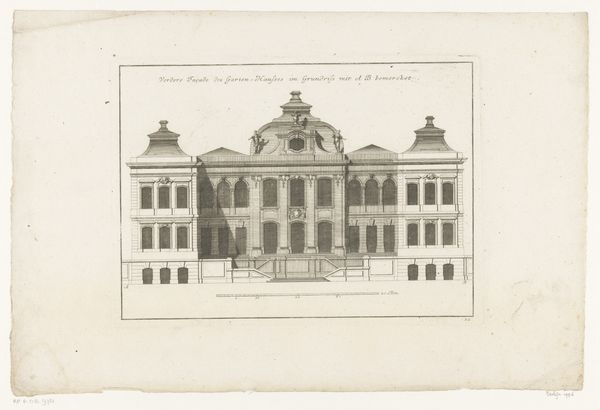

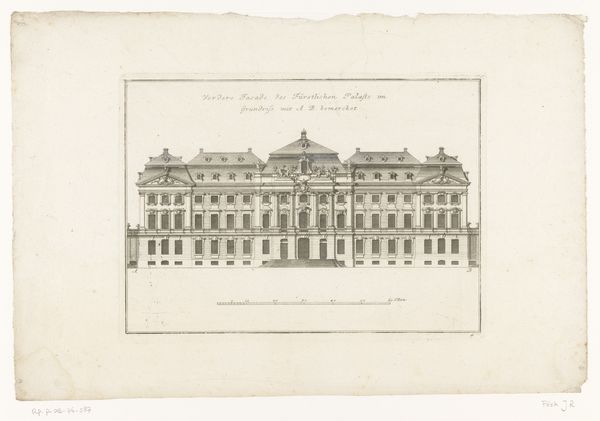

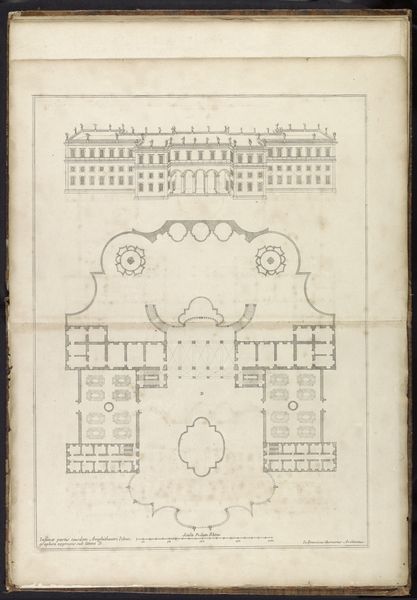

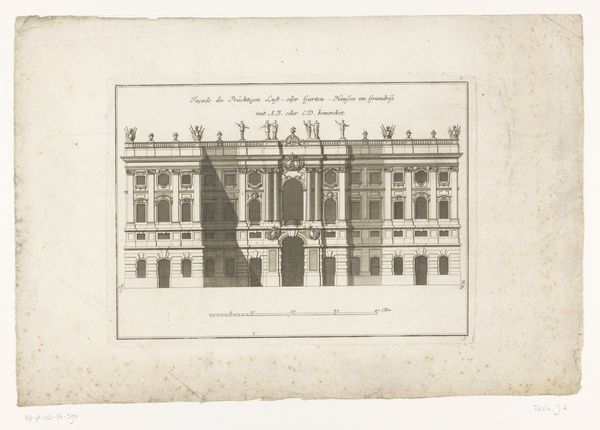

Curator: The symmetry! It’s almost aggressively balanced. Like staring into the face of perfect order. Editor: Exactly! We're looking at H. Terasson's c. 1724 engraving of Blenheim Palace. It meticulously details the facade, bridge, eastern side, and floor plans. It's a blueprint of power rendered in ink. The sharp lines, the rigid geometry—it all screams neoclassicism. Curator: It's…clinical, isn’t it? There’s a distinct lack of…well, anything organic. Even the gardens, if you can see them in this architectural rendering, are implied through stark lines and shapes. Makes you wonder what they left out of the picture to build that palace in the first place? What histories did they pave over? Editor: That's precisely the tension embedded in these kinds of images. The celebration of grand architecture often masks the displacement and exploitation that funded its construction. Blenheim Palace, gifted to the Duke of Marlborough, a military figure, on land seized and transformed into an extravagant estate. The local and national policies behind such estates and gifts certainly need some challenging to consider that what war means back home is to be rewritten through bricks, mortar and wealth. Curator: Right, it becomes this monument not just to one person but to an entire system. Thinking of the design itself, this rigid perfection that it shows isn't life; life's a beautiful mess! Do you think this idealized aesthetic serves a function, of trying to impress or control more effectively? I think of surveillance and how we are building and using tools now as architecture now even more intensely influence power dynamics, social norms, and spatial justice... This building is so uncomfortably controlled and ordered. Editor: The perspective and medium are carefully chosen, to communicate control through these visual choices, in essence a social architecture intended for shaping the cultural perception and justification of its power. We should remember too that even architectural drawings don't often include the living quarters of the workers who would keep such spaces in order, or where enslaved people lived, or even accessible entry points for disabled visitors in the long-term. This print is a very specific vision from a very specific place, about a very specific purpose. Curator: Well, I am going to look into accessible and adaptive use projects happening in similar environments now, because honestly, while it is visually balanced and impressive in scale, my breath actually got a little short looking at that very top-down drawing! It does what it set out to do then. Editor: Absolutely, engaging with such grand depictions means confronting historical omissions and envisioning ways spaces can become more democratic, communal and responsive, shifting away from ideas of sheer wealth towards equity and social utility.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.