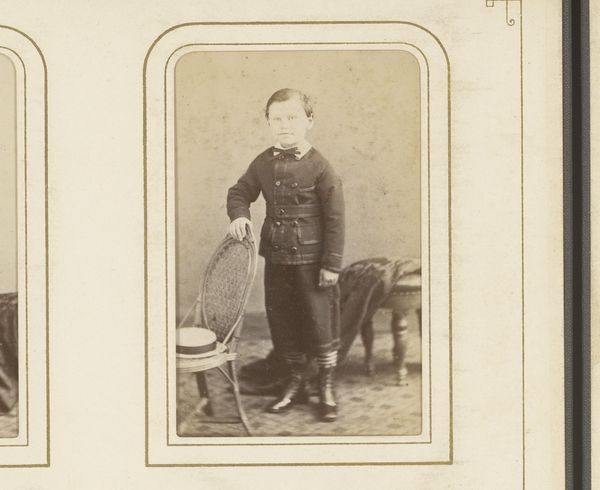

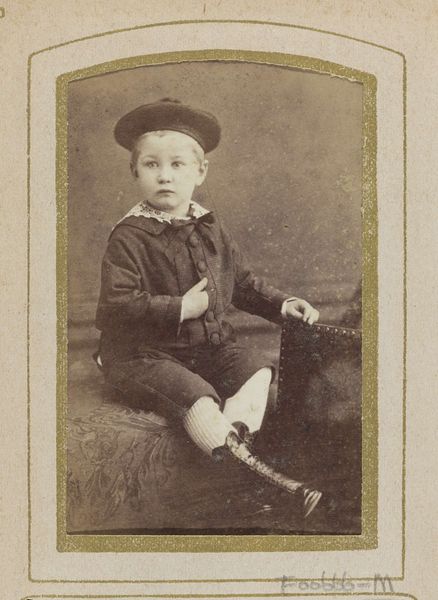

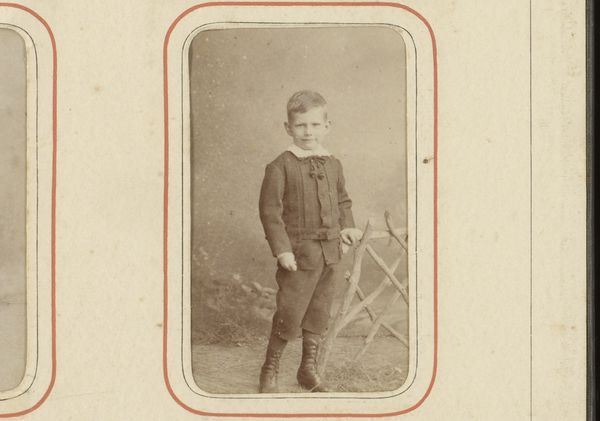

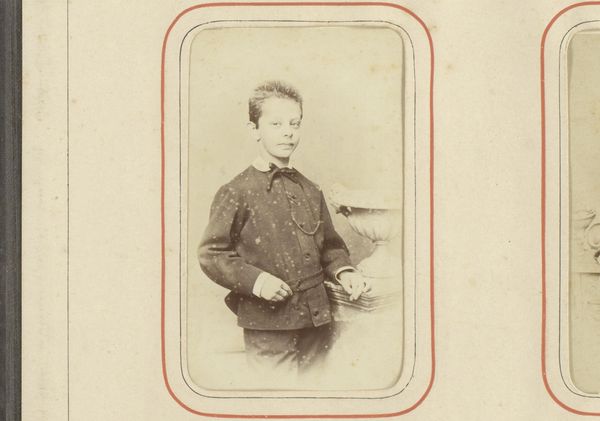

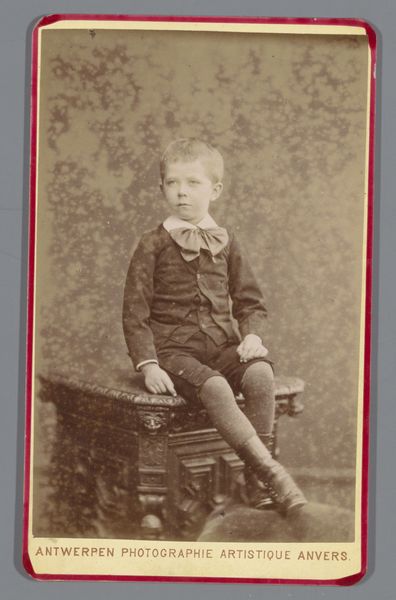

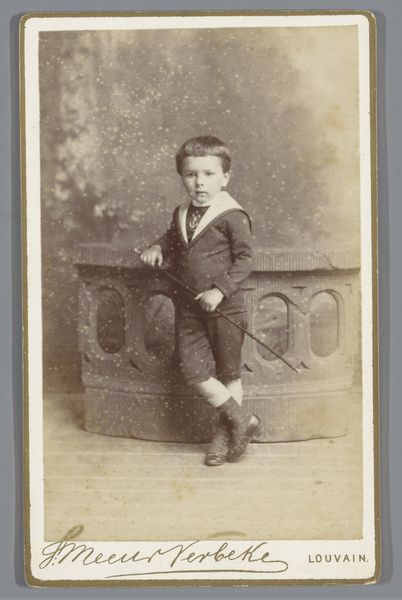

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 166 mm, width 107 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, dating from between 1860 and 1900, is titled "Portret van een jongen"—"Portrait of a Boy" in Dutch. The photographer is Max Kretzschmer. Editor: My first thought is somber. The monochromatic palette certainly contributes, but the boy's posture, combined with his direct gaze, makes me feel like I’m intruding on a private moment. There's a hint of defiance, or perhaps resignation, in his expression. Curator: Exactly, and consider the socio-political forces at play during that era. Photography had become more accessible, but portraits, like this, remained significant statements of identity and social status. The subject's clothing suggests a certain level of middle-class prosperity, reflected by the vest and jacket he wears. Editor: And that clothing, presented to us in the portrait, signifies belonging to a capitalist society. However, does he look comfortable? The costume seems too tight for the person that is inside of the costume. As if what he presents to the outside doesn't reflect what is going on internally. Curator: Interesting perspective. This period also coincided with evolving ideals of childhood. Previously seen as miniature adults, children began to be regarded as individuals with unique emotional and intellectual needs. How might this inform our reading? Editor: The stiffness, the carefully styled hair—it all speaks to the construction of identity. It forces us to confront societal expectations and the lack of agency youth often face. What are the costs, one wonders, of suppressing genuine expression to fit a mold? His is not an empowered self-expression but, most likely, parental imposition. The portrait freezes an artificial state. Curator: And those costs were, indeed, high for many, especially those from marginalized communities where access to such constructed self-representation was extremely limited. Considering the context of gender too: boys were trained to internalize stoicism, to project a façade of strength and control. Editor: A poignant reminder that art—even portraiture seemingly devoid of overt political messaging—is never truly neutral. It’s always participating in larger power structures. It reinforces those expectations as cultural ideals. Curator: Yes, each historical portrait opens into considerations of identity, gender and cultural studies. By observing it carefully, the viewer may come to terms with past conceptions as different, or similar, to contemporary reality. Editor: Thanks to images such as these, a critical reassessment is made more readily available.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.