![Landscape [left of a triptych of White-Robed Kannon with Landscapes] by Kenkō Shōkei](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzBjZTdhZWNkLWI1OWQtNDllYS1hY2I0LWM5YmRlZGRlYTU5MC8wY2U3YWVjZC1iNTlkLTQ5ZWEtYWNiNC1jOWJkZWRkZWE1OTBfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

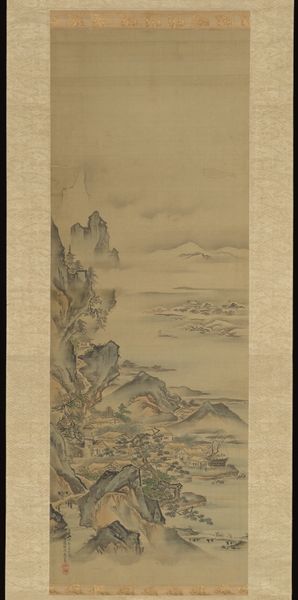

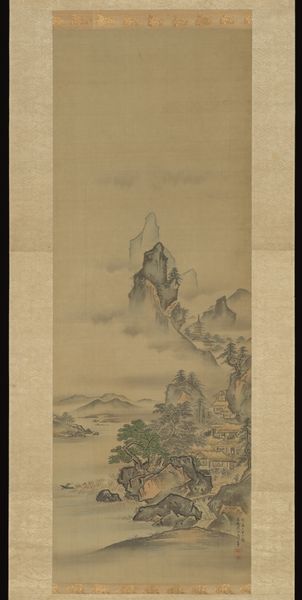

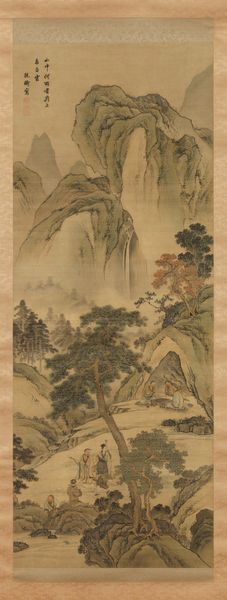

Landscape [left of a triptych of White-Robed Kannon with Landscapes] c. late 15th century

0:00

0:00

painting, ink

#

ink painting

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

japan

#

ink

#

yamato-e

Dimensions: 38 3/8 × 12 13/16 in. (97.47 × 32.54 cm) (image)69 1/8 × 17 1/8 in. (175.58 × 43.5 cm) (without roller)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This ink painting is part of a triptych by Kenkō Shōkei, created around the late 15th century, titled "Landscape [left of a triptych of White-Robed Kannon with Landscapes]." It's currently held at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. What's your initial reaction to it? Editor: I find the misty quality immediately striking. It evokes a sense of serene isolation, almost a dreamlike world, particularly as I consider this was rendered in ink on paper. The very narrow and tall presentation draws me upward to something, some place. Curator: Absolutely. The use of ink is quite sophisticated, considering its inherent limitations. The artist seems less concerned with mimetic representation, focusing instead on suggestion, on what the material, itself, is capable of rendering with light and water. Editor: How might the limited tonal range affect our understanding? Because the lack of sharp color contrasts pushes our eye to search, perhaps inviting a deeper consideration of humanity's role in this terrain. Look there, I think I see someone punting a shallow boat, just barely perceptible! Curator: Indeed. There’s a tension between the raw materiality of the ink, how it behaves on the paper, and the almost ethereal depiction of the landscape. The labor involved in carefully grinding the ink, preparing the paper, each step impacts the final product and viewing experience. Consider that its status as part of a triptych impacts the narrative. Editor: The other panels, presumably featuring the Kannon, could provide a specific context for the landscape – perhaps representing a sacred space, thus imbuing this world with Buddhist undertones and further examining concepts such as purity or detachment. Where is this 'somewhere', literally, but also in some way, existentially? Curator: Precisely. Moreover, we need to understand the availability of materials during the period and what determined artistic practice and reception. Were ink and paper considered commodities for everyday use or luxury materials reserved for spiritual and artistic pursuits, particularly among a specific caste? Editor: Considering the scroll format and its presentation only to a privileged few is key. Was the average person even exposed to landscape representation such as this? Were similar landscapes viewed through radically divergent prisms depending on one’s societal placement, class, and access? Curator: Precisely. Focusing on the interplay between artistic technique, the material, and the socio-historical context surrounding "Landscape," allows us to consider its meaning beyond purely aesthetic terms. Editor: Indeed. Thinking through gendered lenses and class dynamics in regard to artwork and its making lets us examine these representations critically and understand the intersections that generate rich, multifaceted histories.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

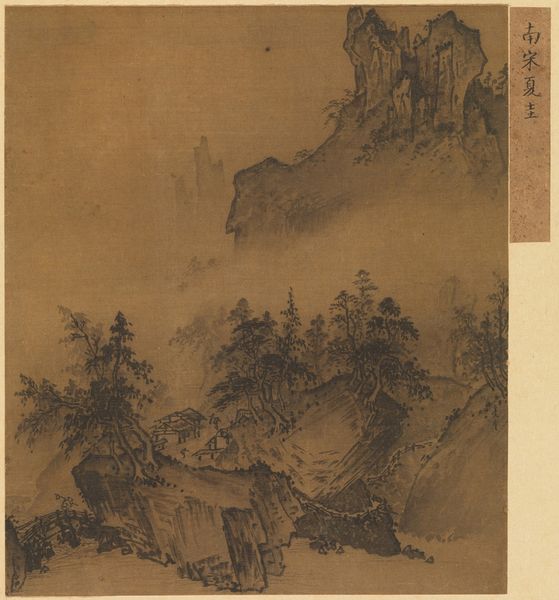

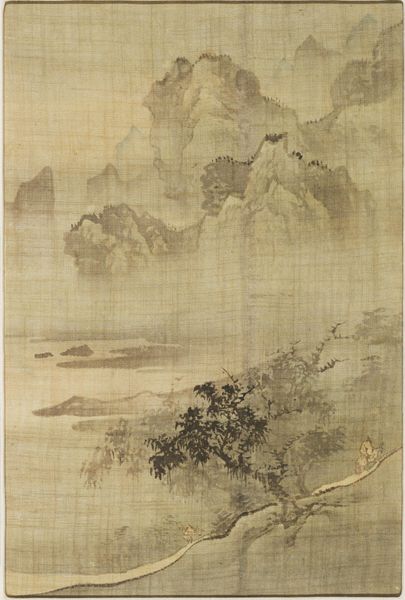

Buddhist monks, particularly those of the Zen school, were devoted landscape painters. Like calligraphy, painting was considered part of the spiritual training necessary for enlightenment. Zen monks favored monochrome ink painting due to its simplicity and straightforwardness. The priest Kenkō Shōkei, who served as secretary at Kenchōji Temple in Kamakura, studied Chinese paintings from the Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1279-1368) dynasties and became a key figure in the ink-painting circles of Japan

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.