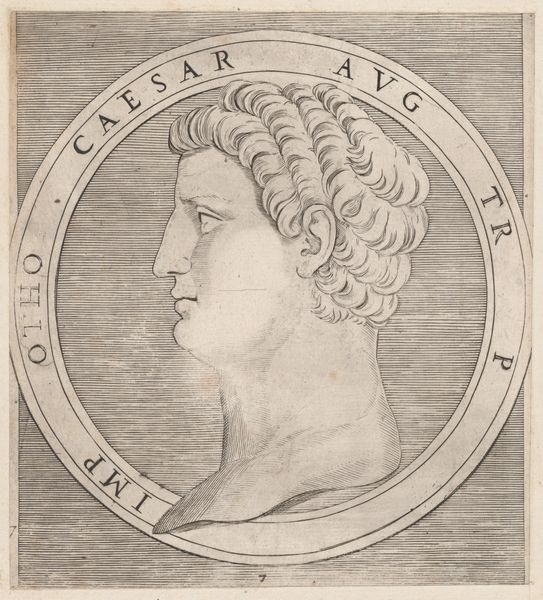

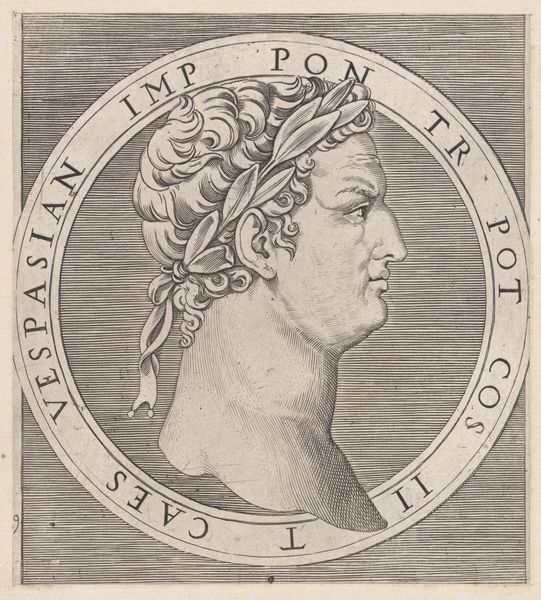

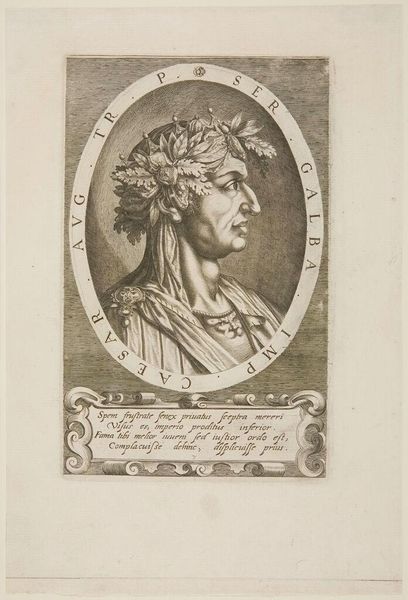

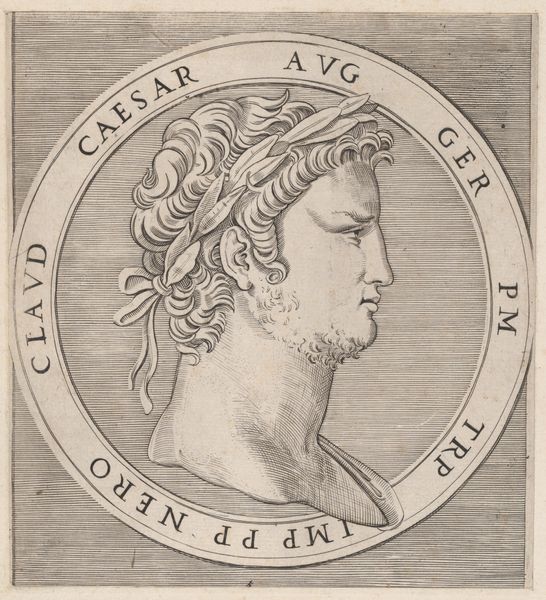

print, engraving

#

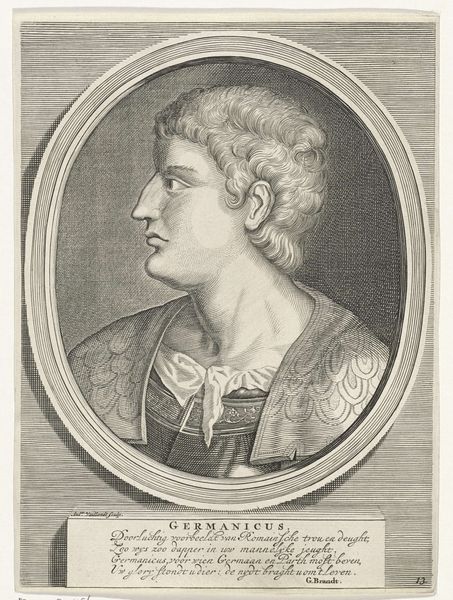

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

classical-realism

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

pen-ink sketch

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 169 mm, width 151 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

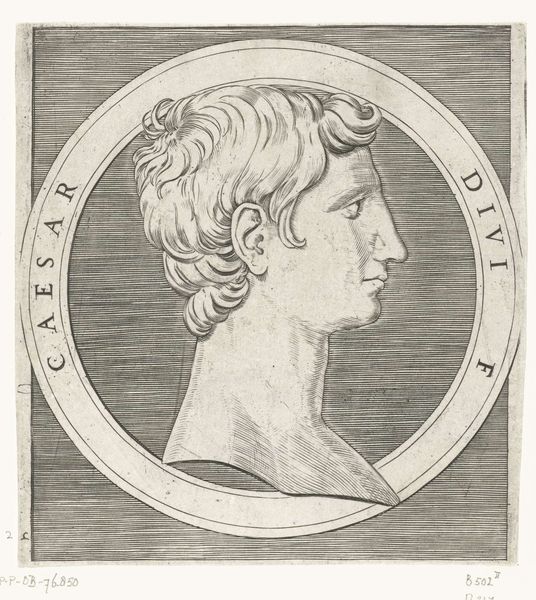

Curator: Here we have Marcantonio Raimondi's "Portret van keizer Otho in ronde omlijsting," an engraving dating from between 1510 and 1527, here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It’s striking, this crisp, clean portrait emerging from a background of tight, uniform lines. There's a strong sense of imposed order and hierarchy, don’t you think? It almost feels clinical despite the curls. Curator: Indeed. The work draws heavily on classical realism, attempting to recapture an antique style. Raimondi was, after all, instrumental in disseminating classical forms during the Renaissance. But this work must be also understood within the socio-political context of the printmaking boom that time, an era defined by its explosion of imagery that was actively shaping ideas about authority and leadership. Editor: Exactly. And that speaks volumes. He isn’t simply portraying Otho, but crafting a deliberate image for public consumption, potentially for propagandistic purposes. The very act of selecting Otho – a ruler from antiquity– implies a particular set of virtues and expectations. It’s interesting to consider how those values may have resonated with contemporary audiences. Curator: Moreover, consider the inscription, it frames Otho’s image not only literally but figuratively as well. Raimondi is asserting, and potentially interrogating, claims of legitimacy and power. Who gets to define Otho, and for what purpose? Editor: And I keep returning to that austere backdrop—the horizontality emphasizing control. The way the face juts out with that nose feels particularly unforgiving, despite the supposed virtues such controlled portraits wish to project. Curator: That’s the tension, isn't it? The portrait style alludes to an ideal, yet the inherent limitations of the engraving technique, the necessary choices, inject something of the engraver's own perspective and, dare I say, an element of humanity, perhaps fallibility? Editor: Absolutely, the materiality itself shapes meaning. That it's a reproducible image makes it extremely powerful: accessible and ready to perform various cultural functions, depending on time and place. So much more than just a portrait. Curator: Right, seeing this in person enriches our perspective on how power gets created and reinforced. The image resonates far beyond its time. Editor: It pushes me to think about what constitutes power and the images that seek to reflect its attributes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.