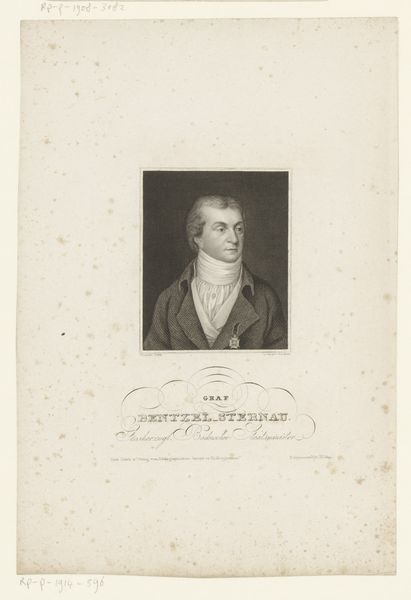

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

romanticism

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 113 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Portret van Franz Volkmar Reinhard," a print created by Carl Mayer sometime between 1828 and 1868. It’s currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's a certain somber quality to it, wouldn't you agree? The etching gives it a very direct, almost documentary feel. I immediately consider the type of labor and precise technique involved in its creation. Curator: Precisely. This somber tone might be because we see a specific depiction, in its representational approach we must question his gender, class, and profession reflected here, elements that constitute his identity and the context in which he moved. His stern expression and formal attire—can we understand something about the values of the era? Editor: Definitely. The choice of engraving itself, a meticulous and time-consuming process, highlights the value placed on craft. How many hours did it take to complete, how many decisions during production? I imagine the artist dedicating their work and attention to produce these images that can circulate information on printed matter. Curator: Absolutely. The materiality and process intertwine with social purpose, even suggesting broader considerations like power and visibility. Editor: You raise an excellent point. The scale of production undoubtedly had a social impact, as it's hard to fathom an understanding beyond labor or its place in disseminating ideas. Curator: Speaking of labor, engravings were frequently used to reproduce paintings. The relationship with realism of painting from life is still there but becomes once removed to spread the images on papers of a portrait and gain circulation as part of visual communication media. This one seems more immediate and connected to Reinhard. Editor: It does present a different level of intimacy than the paintings that came from the romantic era. Still, the quality and reproducibility also democratized portraiture. But what would be the conditions of making these types of print objects from those eras. It seems that many things we miss now. Curator: Agreed, the social implication here. Examining it now, it reminds us to critically consider who had the power to be represented and how they wished to be seen but it remains, how many laborers and types of skill had to involve making this project a reality! Editor: Indeed, something we need to revisit that often. Thinking about material traces and craft as meaningful ways to bridge time with works of art that can carry multiple conversations now and again.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.