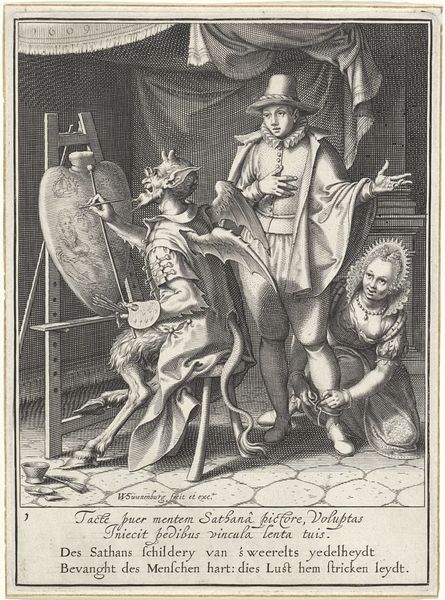

print, engraving

#

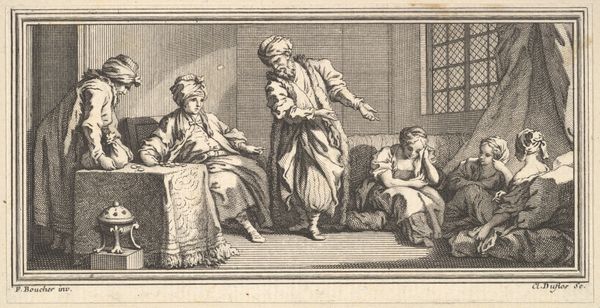

portrait

# print

#

caricature

#

portrait drawing

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 178 mm, width 162 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, here we are looking at “Man offers a young woman money,” a print made sometime between 1638 and 1658. It’s currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Cornelis Visscher is the artist. What catches your eye first about this scene? Editor: Definitely the feathered headwear. Everyone's sporting a bit of flamboyant plumage – feels almost comical, like a play. There’s something dark under the surface, though. The shadows seem a bit deeper, more knowing. Curator: Yes, that sartorial excess contrasts so sharply with the obvious transaction at hand. Visually, that pointing figure – he’s quite shrewd, isn't he? – is driving the narrative forward. Do you see any recurring symbolic motifs that grab you? Editor: Well, immediately the money bag and purse suggests an economy of desire at play. The seated woman looks away, right? There is a mirroring effect to those glances, each turning away from an agreement in process, in the middle the figure seems to broker the financial exchange, or rather to point toward it. Perhaps that tells a narrative about complicity in societal structures. Curator: Precisely, and that makes me think about how these themes echo through art history. The seduction scenes and depictions of female virtue under threat weren't going anywhere anytime soon! How does Visscher convey that here, I wonder? Editor: It's the body language, isn’t it? The gentleman to the left's gentle hand around the young woman is somehow menacing in his restraint, in concert with those forward-thrust gestures that speak volumes beyond their polite exterior. They point like accusations to money in that satchel in the middle. It tells me everything and nothing. There's an anxiety there, a lack of resolve perhaps that points more vividly at the cultural context, than anything being done with the people represented. Curator: You're right to say the tension seems rooted beyond the image. Maybe Visscher felt that tension himself in representing the scene; there’s something uneasy in the observation itself. But it's in that shared ambivalence between subject and viewer, past and present, where art like this finds its lasting power. Editor: Indeed! So many unanswered questions linger long after you've stopped looking... Maybe that is where art thrives after all, those strange and fertile imaginative possibilities beyond us that keep speaking from art over time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.