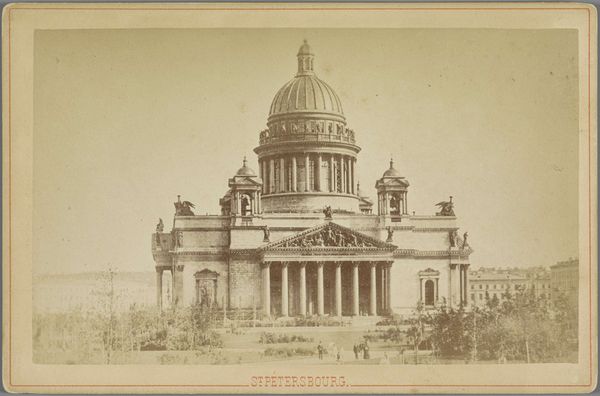

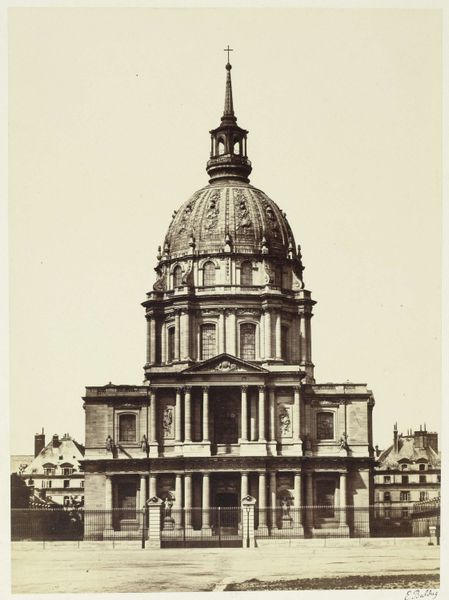

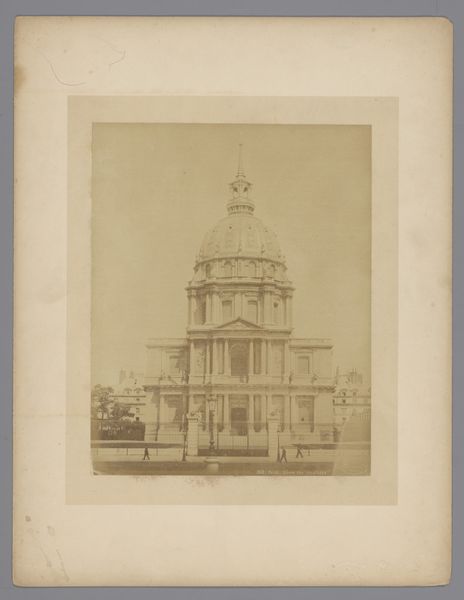

Sint Isaac Kathedraal in Sint-Petersburg, ontworpen door Auguste Montferrand. 1898

0:00

0:00

henrypauwvanwieldrecht

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 100 mm, height 259 mm, width 365 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The print before us, held in the Rijksmuseum, is a photographic cityscape of the Saint Isaac's Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, Russia. The photo, realized in 1898, is credited to Henry Pauw van Wieldrecht. It's an albumen print, which was a popular photographic process at the time. Editor: My first impression is its overwhelming sense of scale; you feel tiny in relation to the immense cathedral that dominates the scene. There's a real commitment to documenting realism that conveys something about the priorities of this period. Curator: Yes, the albumen process yields exceptional detail, which is crucial to understanding its initial function. These photographic prints served a specific purpose, circulating not merely as art objects, but as documents of engineering, architectural achievement, and perhaps even, indirectly, imperial power. Editor: Indeed, the context matters deeply. The Cathedral’s neoclassical design speaks volumes about Russia's aspirations to align itself with European ideals and project imperial grandeur, yet the stark contrast between the monumentality of the building and the figures that occupy the city's space tells us something about individual and social relationships in such societies. The use of photography also represents a critical moment in visualizing those power dynamics and hierarchies. Who is seen, who is seeing, and how that gaze is mediated becomes vital. Curator: And when you consider the laborious and toxic processes required to create albumen prints— coating paper with egg whites, sensitizing it, exposing it, and then developing and toning it— you see the means of photographic production themselves reflecting broader labor practices and industrial progress. The consumption of eggs alone for such enterprise speaks volumes! Editor: That’s a striking point, and a perspective too often overlooked! This print prompts reflections on progress but also questions about whose progress we're celebrating and at what cost, both materially and socially. The workers, the anonymous people who built and maintained the structure and created these images are effectively rendered invisible here. Curator: By bringing all these threads together, from the architectural scale, to the processes involved in capturing the scene, we begin to understand more profoundly not just what we're seeing, but how its materiality and manufacturing affects broader spheres of the period. Editor: It truly encapsulates an era, raising significant questions about the relationship between ambition, labor, and representation, especially from a postcolonial lens.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.