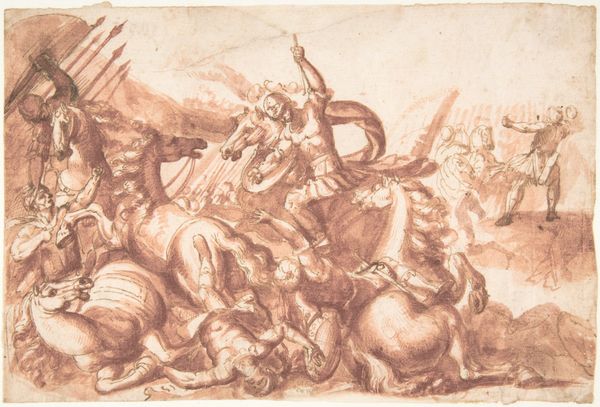

Copy of Battle of Anghiari, the lost painting by Leonardo da Vinci 1603

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, charcoal

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

oil painting

#

group-portraits

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

#

charcoal

Dimensions: 45.29 x 642.62 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: This drawing is titled "Copy of Battle of Anghiari, the lost painting by Leonardo da Vinci" created by Peter Paul Rubens in 1603. It’s rendered in charcoal on paper, and depicts a chaotic battle scene. The intensity and violence of the conflict is quite overwhelming. I’m curious, what narratives do you see embedded within this work? Art Historian: Well, let’s start with the obvious: Rubens made this drawing after a lost Leonardo da Vinci painting. The very act of copying implies reverence, a desire to preserve a fragment of history. Now consider that Rubens was working within the Baroque period – a time marked by religious and political upheaval, particularly the Counter-Reformation. Does the sheer dynamism and brutality depicted here seem to glorify violence, or perhaps critique the socio-political climate of early 17th century Europe? Editor: I see your point. It's easy to get caught up in the drama, but maybe it’s meant to question the power structures that perpetuate this kind of conflict. Art Historian: Exactly. Think about the power dynamics inherent in depicting a battle. Who gets remembered in these grand historical narratives, and whose stories are erased? Consider that art was often used to reinforce the authority of the elite, the ruling classes, who most often commissioned this artwork. Could Ruben’s depiction here act as some subtle pushback? What happens when these scenes of combat, ripped from their historical context, get absorbed as pure action? What about the human cost and what are the consequences? Editor: So, even this reproduction carries complex implications related to power, memory, and how we interpret violence across time? It seems there are layers of history that one may be aware of depending on their lived experience. Art Historian: Precisely. Approaching it this way forces us to engage critically, not only with the artwork itself but also with our own assumptions and biases when we examine it. Editor: That’s really given me a lot to consider. Thanks for broadening my perspective on this Rubens drawing. Art Historian: My pleasure. Looking beyond the surface, digging into context, helps us reveal the multi-layered narratives within. Art always serves as a product of its time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.